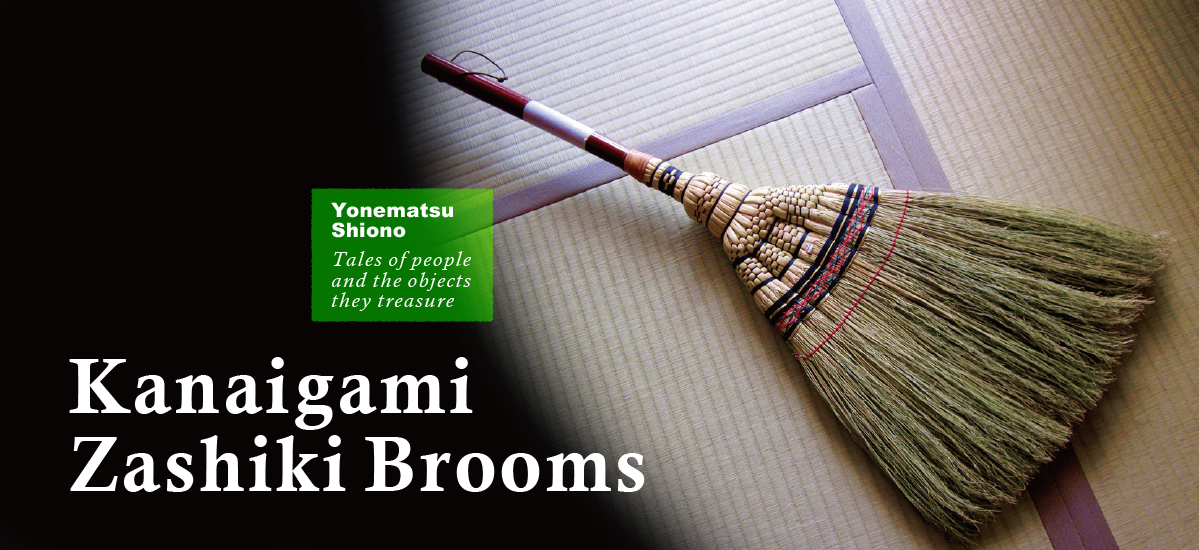

There’s just nothing quite as lovely to look upon as a hand-crafted broom. One of the charms of these humble objects is the time and effort, not to mention the artistic sense, that goes into making them – from the gathering of the materials to the crafting of the final product. Kanaigami zashiki-hōki, traditional hand-crafted ‘parlour brooms’, are not only lovely to look at, they are infused with two hundred years of history.

Text : 塩野米松 Yonematsu Shiono / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : traditional crafts / Yamagata / Yonematsu Shiono / Kanaigami / Japanese brooms / Zashiki Hōki

A Sacred Tool to Rid the Home of Impurities

We have only one zashiki broom left at our place now. We keep it for sweeping the tatami room where we have our Buddhist altar, for, while the vacuum cleaner is perfectly adequate for much of the housework, its noise and commotion hardly seem suited to the sanctity of this particular space. Far more fitting is the soft swish of the zashiki broom as it gently coaxes dust from the room.

When I was a boy, my mother would clean the whole house with a long-handled hand-made broom. The tip of this broom, as it glided majestically over the floor, invariably left a sense of purity in its wake. Indeed, whenever my sister played house, she always did so with a most reverent expression on her face.

Brooms once came in a wide variety of shapes, sizes and materials, depending on where they were made and how they were to be used. Many were made with decorative coloured thread to bind the fibres of the broom together. Yard brooms were made from bamboo or from bundles of dried twigs from the common kochia plant, known as hōki-gusa in Japanese. Meanwhile, concrete or earthen-floored rooms were kept spotless with brooms made from the fronds of the Chinese windmill palm, and a special little broom was reserved for keeping the family altar spick and span.

Because of its role in sweeping away dust and dirt, the humble broom was treated almost as a sacred object. Anyone callous enough to mistreat a broom, or careless enough to leave one lying around, got a jolly good scolding. After all, dust and dirt were not the only impurities brooms could sweep away; they could also rid the house of evil.

It’s traditional at New Year’s to honour various household tools and utensils by placing a mochi rice cake offering in front of them. In our house, there was always a special offering of mochi for the brooms.

Brooms of the World

I have encountered all kinds of traditional brooms in my travels abroad, and I have never yet met one I didn’t like. In Madagascar, brooms that looked just the like classic witch’s broom caught my eye.

These consisted of bundles of barley stalks bound with sisal cord to a wooden pole made from a sapling. I liked them so much that one found its way into my luggage when I returned home to Japan.

In Britain, they traditionally make what we in Japan would call bamboo brooms, which they use to sweep up leaves in the garden. However, lacking bamboo, the British use birch twigs for the brush and slim hazel saplings for the handle.

I sought out a broom craftsman and set off to make his acquaintance. He told me he was the last of his kind and that even the Queen used his brooms. At least, that’s what I think he said, and he certainly had the plaque to prove it, proudly displayed above his door.

While I don’t imagine that the Queen actually uses these brooms herself, what this craftsman did have was a royal warrant to supply brooms to the royal family. The craft of broom-making is disappearing in Britain though, even in that country of gardeners, as they can’t compete on price with twig brooms imported from China and Southeast Asia.

A Traditional Skill Dating Back Two Hundred Years

Meanwhile back in Japan, Tsugamachi (now part of Tochigi City) and Kanuma, both in Tochigi Prefecture, were once thriving production areas for zashiki brooms. Travelling salesmen laden with brooms would once set out from here to peddle their wares throughout the provinces. The bristles of these traditional Japanese brooms were made from hōki morokoshi, a variety of sorghum known in English as broom corn. The one we have at home is from another broom-producing centre where such brooms have been traditionally crafted in farming households for around two hundred years, the hamlet of Kanaigami in Nagai City, Yamagata Prefecture.

There’s always a story behind the introduction of a new craft to a particular area, generally along the lines of a traveller, often an itinerant Buddhist preacher, teaching folk a new skill to thank them for their hospitality. In Kanaigami, so the story goes, the village folk offered shelter to a travelling merchant during a blizzard, who in turn left them with not only the broom-making technique, but also the broom corn needed to make the brooms. Ever since, the people of the hamlet have planted the seeds at the beginning of summer, harvesting the fast-growing plant two months later.

The brush-like tips of the stalks are threshed to remove the seeds, then dried to be used for broom-making, along with the outer layer of skin peeled from the stalks themselves. The making of the brooms traditionally takes place indoors over winter.

According to the late Yogorō Tsuchiya, former chairman of the Kanaigami Hōki Association, the way the skins of the stalks are used is a distinctive characteristic of Kanaigami brooms. When asked what was the most difficult aspect of making these brooms, Yogorō san would always jokingly say, “It’s all difficult and it’s all easy”.

Putting the Beauty Back into the Mundane

Broom corn is a fast-growing plant that quickly reaches a height of two metres. Unlike ordinary corn or maize, the plant does not produce side shoots. Each plant yields only one brush-like ear of grain, and as many as one hundred plants are required to make each broom.

The long, brush-like fibres of the seed tips are bundled together with lengths of stalk at the base, and are repeatedly pounded with a wooden mallet to soften the stalks and shape the broom as the materials are woven together and more material is added.

The base of the broom where the brush meets the handle is interwoven with colourful thread, forming a decorative binding.

The brush section of the broom is formed into an asymmetrical shape, sweeping out to one side like the wing of a bird. The fibres of the brush are again bound with rows of coloured thread at intervals from the base towards the tips to maintain this flattened wing-like form, and to preserve the spacing between the bundles of bristles.

The different colours, blue, red, green and black, and the varying thicknesses of the twisted threads lend a certain air of elegance to the broom.

Once the brush section is ready, the broom handle is attached. Scorched cedar poles, which stand up well to the cold winters, were used in the past but the handles are now made of bamboo, which is lighter and easier to work with. However, as the type of bamboo used doesn’t grow in this region, it has to be ordered in. Even traditions, it would seem, change over time.

As finishing touches, decorative nails are hammered in to hold the handle in place, and traditional embroidery patterns such as “Taka no Hane” (Hawk Feather) or “Yamamichi” (Mountain Path) are applied to the base of the brush.

These hand-crafted brooms were once sold at end-of-year fairs, and purchased to sweep the home clean of impurities and usher in the new year. Yogorō san proudly told me that a Kanaigami broom will last at least ten years. These unique Kanaigami brooms are both beautiful and hard-wearing.

Amongst all the bustle and noise of modern-day life, a traditional Kanaigami broom imparts a reassuring sense of calm and quiet that a vacuum cleaner simply cannot offer. Perhaps it’s time to inject some beauty back into the mundane chore of daily housework.