Nambu Tekki Ironware – Kamasada Iron Casting Studio, Morioka City, Iwate Prefecture

Text : 塩野米松 Yonematsu Shiono / Photos : 菅原孝司 Koji Sugawara / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Nambu Tekki / traditional crafts / craftspeople / Nanbu Region / Northern Japan / Iwate

Unassuming exterior offers little hint of the wonders within

In a narrow street in Kon’ya-cho, Morioka City, sits a pretty little Japanese-style white building with a tiled roof and traditional white plaster grills over the windows. A simple navy blue and white noren is stretched above sliding glass-paned doors and the square white sign standing next to the steps reads ‘Kamasada’. The building has the look of a handicraft store – or maybe even a cafe – but this is the home of the cast iron foundry, Kamasada.

First-time visitors to Kamasada might even wonder if they’ve come to the right place. But once they pop their heads through the door they notice the iron trivets and ashtrays set out on a raised tatami display area, and the pots and kettles lined up on the shelves, and know they’ve arrived.

The modern forms of a traditional craft

The ironware industry was introduced to the Nambu region (the area around Morioka City) during the mid-17th century by craftsmen from Kyōto, under the patronage of the local daimyō (feudal lord). It developed into a thriving industry here because there were plentiful supplies of locally extracted iron ore, good sand suited to making the molds, and good quality charcoal to fire the furnaces. Moreover, there were people willing to perfect the craft.

With the abolition of the feudal system at the end of the Edo Period (1603 – 1868), local iron foundries lost the patronage of the wealthy feudal lords and had to compete with each other for customers. Not all foundries withstood the competition; nor did they all withstand the test of time. Those that did, however, are the Nambu Tekki foundries that remain to this day.

A long history and world-renowned reputation can be a double-edged sword for a traditional industry. The general public might assume that the products are more like museum pieces than useful items that are relevant to today’s lifestyles. Traditional artisans have had to overcome this perception in order to be able to move forward, constantly striving to ensure their products remain relevant while retaining the integrity of their tradition.

Kamasada have embraced this issue wholeheartedly for three generations. Their success and the determination of each subsequent head of the family shows in the elegant presentation of this store and the beauty and artistic flare of the wide range of ironware products inside.

Embracing the changing times with an artistic spirit

The Kamasada iron casting studio and showroom were built by first generation owner, Sadakichi Miya, who was born in 1885. Kamasada’s core business is making iron kettles, particularly chagama, the iron kettles used in tea ceremony. In simple terms, the process of making pots and kettles involves pouring molten iron into a mould. Sadakichi employed skilled craftsmen and produced a range of ironware including tea kettles and pots. He passed away in 1931 at the age of forty-six and was succeeded by his son, second generation Shōtarō.

After attending a commercial secondary school, Shōtarō studied at the Sendai Industrial Arts Training Centre. An artist in his own right, he later chose to work as a sculptor, and frequently exhibited his work. Shōtarō studied design in Europe and was also a founding member of the Japan Craft Design Association. This was an unusual path for a craftsman from an iron foundry and quite a step away from the traditional apprenticeship system. Shōtarō continued to refine his skills as a metal craftsman, creating pieces of art and studying design so that he could bring his own interpretation to traditional and classical ironware.

It would be wrong, however, to think that Shōtarō turned his back on conventional foundry work. In fact, he built on the work begun by his father by creating new commercial ironware products with refined forms and he found new avenues for bringing his innovative products to the public. His works of modern design were displayed in the showrooms of Japan’s new department stores, and still remain a popular part of Kamasada’s staple product line.

A tradition that retains its lustre throughout the years

Japan’s northern Tōhoku region was not unaffected by the Second World War, and the Kamasada premises were completely demolished. The home and premises that stand today were rebuilt by Shōtarō over a nine-year period after the war, so that they now appear just as his father left them.

Shōtarō passed away at the age of 55 and was succeeded by his son, third generation Nobuho Miya, born in 1952. Nobuho was only sixteen when his father died, and did not join the family business immediately. Like his father before him, he struck out in search of his own path, studying design at Kanazawa College of Art and later attending graduate school at Tokyo University of the Arts. Nobuho also made a name for himself overseas. He studied design in Finland and exhibited his work in several countries, winning many prizes.

Now, as a skilled Nambu Tekki craftsman, he has achieved worldwide renown.

Iron as a medium of artistic expression.

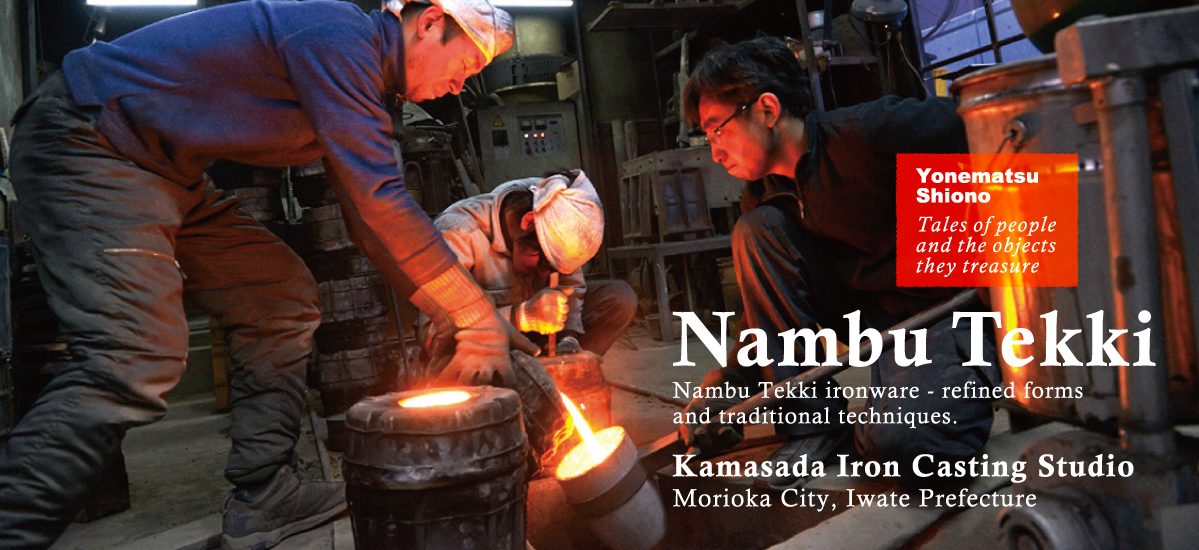

In a workshop that appears just as it did in his grandfather’s time, Nobuho hones his craft. Layers of clay, sand and charcoal worked into the earthen floor speak of the generations who have worked here. All around are rows and stacks of moulds, with the sound of the furnace a constant presence.

All three generations heading the Kamasada foundry have been artists in their own right, with iron as their preferred medium.

The craftsmen as Kamasada continue to explore and experiment with their medium of molten iron, just as they did in times past. How best to express the inherent qualities of the iron; how to bring out its weight and its subdued dignity? These qualities are what is drawing everyone back to the use of chagama and tetsubin, iron tea kettles and pots.

Moving with the times, Nobuho has installed a high frequency induction furnace. However, for his own projects he uses an old-fashioned clay furnace dubbed ‘the rice cooker’. He also uses wazuku or Japanese pig iron, created through the centuries-old process of making tama-hagane (‘jewel steel’), essential for Japanese sword-making.

Wazuku is difficult to work with, but it has a unique texture and a lovely reddish-brown hue.

Third-generation iron craftsman Nobuho Miya’s mission has been to pursue new forms using traditional techniques and experimentation. It is through experimentation at Kamasada that new techniques and knowledge are born – after all, as Nobuho says, “If you don’t try, you’ll never know”.

The ironware at Kamasada Iron Casting Studio tells the story of the love of the craftsmen who create these elegant forms, spurred on by a constant sense of challenge.

Kamasada Iron Casting Studio

2-5 Konya-chō, Morioka City, Iwate Prefecture

Access: Kamasada Iron Casting Studio is approximately 2.2 kilometres from Morioka Station, or around 12 minutes by car/taxi. Alternatively, take the Funakoshi Ekimae bus from Morioka Station and get off at the municipal offices, Kencho Shiyakusho-mae. From there it’s a five-minute walk to Kamasada.

Tel: 019・622・3911