Japan’s unique landscape is filled with breath-taking beauty and vistas that inspire and delight. In this series, photographer Kenji Aoyagi brings us significant landscapes, rich with history and worthy of preservation.

This time we go to Fukushima Prefecture and Ōuchi-juku, a picturesque village of preserved thatched houses dating back to the Edo Period.

Photo&Text : 青柳健二 Kenji Aoyagi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Shimotsuke Kaidō / Edo Period / Ōuchi-juku / Fukushima Prefecture / Isabella Bird / Tsuguō Aizawa / Kayabuki

A Trip Back in Time

Ōuchi-juku is a former shukuba, a post station town established during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) on the 125 kilometre-long Shimotsuke-kaidō route which once linked the domain of Aizu with the post town of Imaichi in the Nikkō area. Leaving Aizu and heading south, Ōuchi-juku was the third shukuba along the feudal highway, after Fukunaga-juku and Sekiyama-juku.

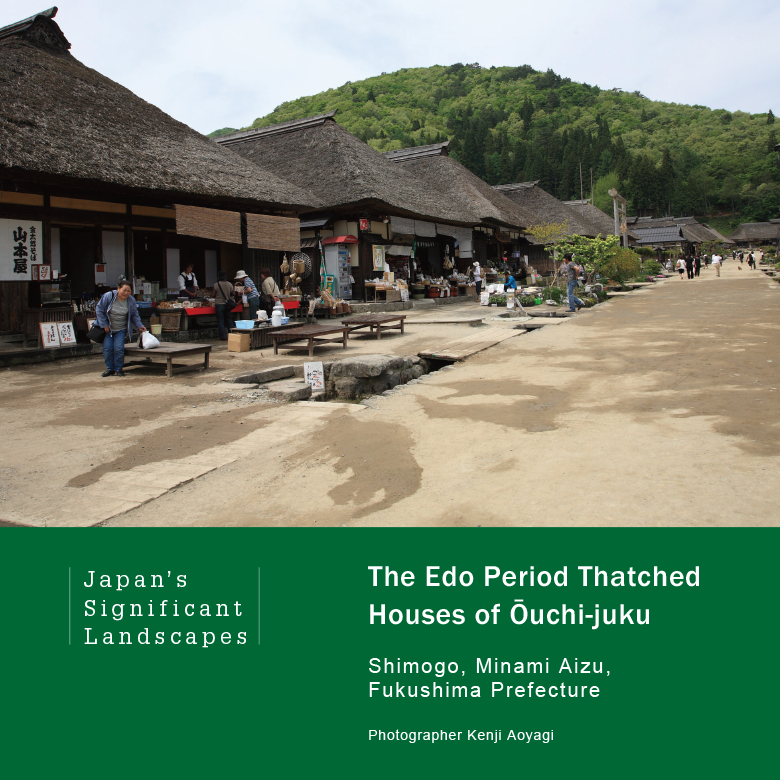

The unpaved main street and thatched-roof houses of Ōuchi-juku have been preserved and power lines put underground, so the village looks very much as it would have during feudal times. Visitor parking is provided at the northern and southern ends of the hamlet some distance away from the preserved streets, which are bustling with visitors but mercifully free of vehicles.

A steep set of steps at the northern end of the hamlet takes you up a wooded hillside to the Koyasu Kannon Temple and an observation spot that offers sweeping views across the village.

The climb will leave you out of breath but it’s worth it-the view is breathtaking! The rows of thatched houses down below look just like a scene from the Edo Period.

Once down from the viewing spot, you can take your time looking through the attractions the town has to offer, including the museum housed in the former Honjin, the principal inn for high ranked government officials.

The constant sound of running water from the irrigation channels on either side of the street provides a pleasant accompaniment to a stroll through the hamlet, as we stop to eat some soba and peek in at the many souvenir stores along the street.

As dusk falls, the shopkeepers begin to take their wares inside and shut up shop. This leaves less to look at but there are also far fewer tourists left now, so I can definitely recommend staying until late in the day.

Any visitors who do linger until dusk are rewarded with a sense of how this old post town must have felt back in the feudal era.

The Site of a Bloody Battle at the End of the Feudal Era

The Edo Period sankin-kōtai system, which sought to maintain control over Japan’s feudal lords by requiring them to reside in Edo during alternate years, meant that the Shimotsuke Kaidō was an important route used by the northern domains of Aizu, Shōnai, Yonezawa, Shibata and Murakami on their processions to and from Edo.

The route was also important for the delivery of rice and other goods to Edo.

Records show that feudal lord Date Masamune’s troops moved through Ōuchi-juku on their way to join warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s 1590 Siege of Odawara, and that Hideyoshi’s troops in turn passed through on their way north in Hideyoshi’s punitive Ōshū-shioki action against the Tōhoku warlord for his reluctance to join the Odawara campaign.

Almost three centuries later Ōuchi-juku was the scene of a battle between imperial troops of the new government and Aizu forces loyal to the feudal shogunate. The battle, which was part of the 1868-69 Bōshin War, took place in late August, 1868. Defeated, the Aizu samurai forces retreated to their last line of defense at Ōuchi-tōge Pass.

As they withdrew, they prepared to set fire to the village of Ōuchi-juku to prevent it into the hands of the imperial troops. However, thanks to the frantic pleas of the villagers, led by village headman Abe Daigorō, Ōuchi-juku was spared.

English Traveller Isabella Bird Visits Only Ten Years after the End of the Feudal Era

In 1878, only ten years after retreating samurai forces had almost razed the post station town of Ōuchi-juku, English traveller and diarist Isabella Lucy Bird spent a night here on her way north. Her brief stay is recorded in her travel journal, Unbeaten Tracks in Japan, published in 1885.

Isabella Bird arrived in Yokohama on May 21st, 1878, having made the Pacific crossing from San Francisco. She spent four months from June to September of that year travelling throughout the Tōhoku region and into Hokkaidō.

Travelling through northern Japan in those days was arduous at best and sometimes downright gruelling. Forty-six year-old Bird, accompanied by her eighteen-year-old Japanese translator and manservant, Itō, was the first European woman (and in many cases, the first European) to make such a journey. Her highly Eurocentric but frank account (Bird “writes the truth as (she) sees it”) of the Tōhoku region, crippled as she says by centuries of taxation, remains as a valuable historical document.

On the morning of June 27th, Bird left Kawashima and followed the Aga River north before leaving the river and heading into the mountains, arriving at Ōuchi-juku in the evening.

“I slept at a house combining silk farm, post office, express office, and daimiyô’s rooms, at the hamlet of Ouchi, prettily situated in a valley with mountainous surroundings, and, leaving early on the following morning, had a very grand ride, passing in a crateriform cavity the pretty little lake of Oyakê, and then ascending the magnificent pass of Ichikawa.”

Although she doesn’t mention the name of her lodgings in Ōuchi-juku, the only place that operated as a post office and transport depot in the village was Minoya, the home and business premises of the Abe family who had for generations been the head family of the village.

Also referred to as the Abe-ke, Minoya, which still serves as a post office today, is located in the north of the hamlet. The building was constructed in the final years of the Edo Period, somewhere between 1865 and 1868, so would still have been new at the time of the battle that took place here in 1868.

A single-storey timber building with a heavily-thatched yosemune roof, the Abe house operates nowadays as a souvenir shop, while a related business along the street, also called Minoya, operates as a soba noodle restaurant.

Preserving a Village Spared by Progress

The abolition of the feudal system in 1868, and the opening of the Nikkō Kaidō route (now National Highway 118) in 1884, meant the end of Ōuchi-juku’s role as an important post station town.

Disconnected from the kaidō highway network, Ōuchi-juku was completely bypassed by the main flow of people and goods. The unintended consequence of Shimotsuke Kaidō’s fall from favour was that the rows of thatched houses at Ōuchi-juku were not demolished when roads were modernised.

However, there was no sense at that time that the buildings had any merit or that they were worthy of preservation. Awareness of the hamlet’s historical and architectural significance would not develop until almost a century later, spurred by the visit of a young architecture student from Tokyo.

Tsuguo Aizawa (now Professor Aizawa) was a fourth-year architecture student from Tokyo’s Musashino Art University, who came to Ōuchi-juku in 1967 to conduct a field survey and would end up dedicating years to ensure the preservation of the houses there.

Almost three centuries later, Ōuchi-juku was the scene of a battle between imperial troops of the new government and Aizu forces loyal to the feudal shogunate. The battle, which was part of the 1868-69 Bōshin War, took place in late August, 1868. Defeated, the Aizu samurai forces retreated to their last line of defense at Ōuchi-tōge Pass.

While lodging in Ōuchi-juku, he tried to persuade the villagers of the need to preserve their centuries-old houses, but not all the villagers shared his opinion.

Many, understandably, longed to live in comfortable modern houses and thought of the old thatched houses as relics of the past, stark reminders of the hardships of feudal times.

However, the young Aizawa was determined, and continued in his attempts to persuade the villagers and local government officials. Finally, in April of 1981, Ōuchi-juku was designated an “important preservation district of historic buildings”, becoming the nation’s third shukuba town to achieve this designation, after Nagano Prefecture’s Tumago-juku and Narai-juku.

The grassroots Ōuchi-juku Preservation Society was formed in September of the same year and efforts to preserve the houses began in earnest. Local attitudes towards the significance of the hamlet had changed and a sense had developed that the old buildings must be preserved for future generations.

The whole village began learning and passing on traditional roof-thatching techniques and a charter was drawn up based on three principles – that the houses could not be sold, rented out, or demolished.

Once a bustling post station town on a main route, Ōuchi-juku, having lain forgotten for almost a century, has now reinvented itself as a popular and bustling tourist destination. The aftermath of the 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake saw a temporary drop in visitor numbers, but Ōuchi-juku bounced back, with 800,000 visitors in 2018, 40,000 of whom were from overseas.