The bright red ō-torii gate of Itsukushima Shrine stands massive and dignified, reflected upon the surface of the azure sea surrounding it. This is the first glimpse visitors to Itsukushima Island catch of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, Itsukushima Shrine. The shrine itself is an architectural work of extraordinary beauty, set against a backdrop of primeval forest and appearing to float on the tide. Above all, though, this is a deeply religious Shintō space that reflects the profound reverence for nature held by Japan’s ancient Shintō faith.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photos : 谷口哲 Akira Taniguchi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : World Heritage Sites / Japan World Heritage / Itsukushima Shrine / Heian Period / Hiroshima Prefecture / Miyajima Island

A warlord’s act of faith brings prosperity to Itsukushima

The entire island of Itsukushima, centred on its highest peak, Mt Misen (535 m), has been an object of nature worship since ancient times. The original meaning of “Itsukushima” is “the island where the gods are worshipped”. These days, the island is also popularly known as Miyajima, meaning “Shrine Island”. Because Mt Misen was considered a sacred embodiment of the gods, the peak was worshipped from the sea or from the opposite shore, rather than setting foot on this sacred land. People were forbidden to live or farm on the island itself. Even after settlements were later established on Itsukushima, no births were permitted on the island. Whenever someone from the island died, the family had to leave Itsukushima for the duration of the mourning period.

This long, narrow island is about 30 kilometres in circumference and lies around 500 metres from the mainland at its nearest point, across the Ōno Strait. The mountainous terrain rises steeply from the coastline and aside from the shrine area, there is very little flat land at all. One of the features of the dense blanket of primeval forest that cloaks this sacred island of the gods is the unusual mixture of cold-climate conifers and warm-climate plants flourishing alongside each other. The entire Misen Primeval Forest has been designated as a special natural monument.

Itsukushima Shrine is believed to have been established in 593, built by Saeki no Kuramoto, the head of the area’s most powerful clan. The shrine was then dedicated to the three goddesses, Ichikishima-hime no Mikoto, Tagori-hime no Mikoto and Tagitsu-hime no Mikoto. Later, at the end of the Heian Period (794 – 1185), the powerful warlord, Taira no Kiyomori, began the construction of the shrine pavilions in the layout that we see today and lavished much wealth on the island.

A grand shrine gate built to withstand the forces of wind and sea

Itsukushima Shrine is on the northern side of the island, built over a small inlet in Arinoura Bay, facing the nearby mainland. It is believed to have been completed in 1168. Taira no Kiyomori, who had become the governor of Aki Province (now Hiroshima Prefecture), ordered the construction but carrying out those orders fell to Saeki no Kagehiro, the shrine priest of Itsukushima and loyal Kiyomori servant.

The grand ō-torii shrine gate, the iconic symbol of Itsukushima Shrine sits about 200 metres out into the bay.

Measuring 16.6 metres in height with 10.9 metres between the pillars and weighing around 60 tons, the ō-torii is constructed in the ryōbu-style with additional pillars in front of and behind each of the main torii pillars.

The upward-curving lintel at the very top consists of two parts: the roof-like kasagi, and the shimagi timber beneath it. The current torii was constructed in 1875 and is the eighth shrine gate to stand here since the Heian Period.

This monumental shrine gate is held in place by its own weight. Rather than being buried in the sea bed, its massive pillars sit atop log pilings. The 60-ton weight consists not only of the timber structure itself, but also of hundreds of small rocks placed inside the box-like structure of the upper lintel, for ballast.

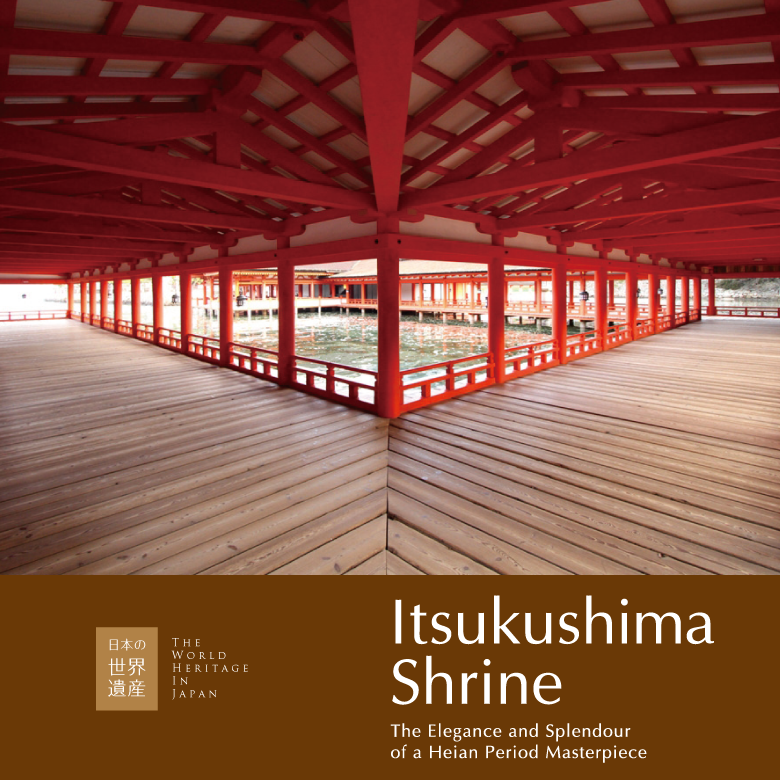

The main pavilions of the shrine are arranged one in front of the other along a north-west to south-east axis extending out from the bay towards the ō-torii. The covered walkways that connect the various buildings zig-zag their way through the complex from the eastern and western shores of the inlet. The pavilions of the main shrine consist of the honden (main hall) towards the rear of the complex, the heiden (offerings hall) in front of that, the haiden (prayer hall) and finally, the haraedono (purification hall), facing out to sea and the great shrine gate. A large, flat, uncovered stage area extends out in front of the haraedono. In the centre of this is a raised platform the taka-butai (raised stage), which looks directly out across the water to the dignified form of the great shrine gate.

Designed with the possibility of natural disaster in mind

Approaching the shrine along the East Corridor, one first encounters the Marōdo Shrine, which faces west towards the main shrine pavilions. Although on a comparatively smaller scale than the main shrine buildings, the Marōdo Shrine also has its own honden, heiden and haraedono. On the far side of the main shrine buildings along the West Corridor are two more auxiliary shrines, Daikoku Shrine and Tenjin Shrine. A little beyond these, out in the water, is the Noh stage. The main shrine pavilions, the Marōdo Shrine, and the East and West Corridors are among the six registered national treasures of the shrine complex.

Being located on the sea, the possibility of damage from typhoons and other adverse weather events is a real and constant threat. The inner sanctuary of the main shrine was built in Kiyomori’s time in a position where it would not be inundated by rising tides, and has never been damaged by the sea. However, the hirabutai stage and the Noh stage, both of which were added after Kiyomori’s time, have indeed suffered damage in the past. Nevertheless, steps were taken at the time of building to prevent these two stages and surrounding walkways from being lifted by rising seawater, and also with a view to making the job of repairing damage easier. They were constructed with slight gaps between the floorboards to allow the water to pass through, while the balustrade around the pavilions and the pillars supporting them can be separately removed and replaced without affecting the integrity of the structures.

The majority of the present shrine complex was rebuilt in 1241, while the main hall was replaced in 1571 by the warlord, Mōri Motonari. Nonetheless, the reconstructions were scrupulously accurate to the original 12th and early 13th century Heian Period style.

Ensuring the preservation of this Heian Period masterpiece

Prized for its architectural and historical value, Itsukushima Shrine was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996. In addition to the grand ō-torii shrine gate and the structures of main Shintō shrine complex, three structures of Buddhist architecture are included in the world heritage listing. These are the five-storey pagoda and the main hall of Toyokuni Shrine just outside of the complex, and the Tahōtō two-storey pagoda, which were built in the 15th and 16th centuries. They are valued for the story they tell of the many centuries when the beliefs and customs of Shintō and Buddhism were entwined, and of the attempted separation of the two belief systems by the government after the 1868 Meiji Restoration. The main hall at Toyokuni Shrine was built by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the 15th century as a great Buddhist sutra hall. After the Meiji Restoration and the forced separation of Buddhism and Shintō, this grand building lost its Buddhist function and came to be known as Senjōkaku (the Hall of One Thousand Tatami Mats).

In order to safeguard the heritage and integrity of Itsukushima Shrine, the entire island, including the township near the shrine and part of the sea, form a buffer zone in which development is strictly controlled. From the end of the 14th century, the hill on which the five-storey pagoda stands formed a boundary dividing the township into east and west. Those associated with the shrine itself lived west of the pagoda, near the shrine. A lavish priest’s residence built in the mid-Edo Period still stands here and the area is full the grace and charm of the past. Meanwhile, in the eastern section of the township, which has always had more of a focus on the harbour and commerce, concerns have been raised about multi-storey hotel buildings and unsympathetic commercial signage that detract from the historical townscape. There seems to be no ready solution to this tension between preserving the historical integrity of popular heritage sites and the need to cater for the visitors who come to see these sites.

Despite these tensions, it is the sea that lends Itsukushima Shrine its scenic beauty and it is the sea that presents the greatest threat. The danger posed by adverse weather events such as typhoons cannot be avoided, but in the face of recent climate change, rising sea levels and the greater frequency of severe storms are of increasingly grave concern. It is hoped that experts from a range of academic fields such as geophysics, civil engineering and architecture will be able to pool their knowledge for the sake of the continued preservation of this magnificent World Heritage Site.