The management of plant resources in Japan can be traced back across a span of some 10,000 years. Agricultural food production in Japan has traditionally been dominated by the cultivation of grains and vegetables, with animal husbandry being a relatively minor and in many parts of the country more recent feature of the agricultural landscape. In this series we explore iconic Japanese agricultural products including not only famous food ingredients, but also other products cultivated from the land such as fibres, dyes, resins and forest products, with an emphasis on quality and tradition.

Photos and Text : Judy Evans

Keyword : Horticulture / Japanese Farms / Wasabi

Real Wasabi

More to this humble herb than meets the eye

Wasabi, the spicy green paste served with sushi and sashimi. Many fans of Japanese cuisine are probably aware that much of this brightly-coloured pungent paste is an imitation product made from a mixture of European horseradish, mustard, food colouring and ‘flavours’. Not that there’s anything inherently wrong with this product, found in supermarkets and widely used by inexpensive sushi chains. It meets a global consumer demand that cannot be met by real wasabi, with its limited production. However, if you’ve only ever tried ‘tube wasabi’, it’s possible you’ve never experienced the real thing.

A shade-loving mountain herb

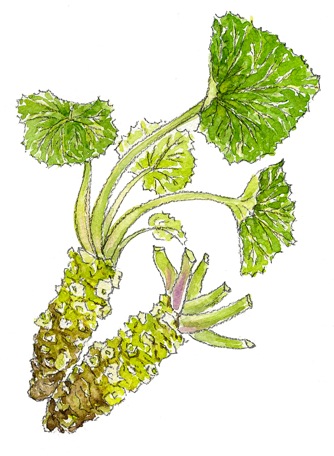

Real wasabi comes from the swollen stem of the Japanese wasabi plant, Eutrema wasabi (sometimes known as Wasabia japonica or Eutrema japonica).This perennial plant belongs to the family Brassicaceae, a veritable culinary tribe that includes horseradish, mustard, watercress and cabbage, to name just a few.

The successful commercial cultivation of wasabi requires specific growing conditions that limit where it can be produced. This in turn limits the supply. Like watercress, wasabi grows naturally in cool, clear mountain streams. Under cultivation, wasabi is often grown in gravel beds flooded with spring water and under black shade cloth in summer to mimic the naturally cool, filtered-light conditions it prefers.

It can take two to three years for the wasabi rhizome (the thickened stem) to form, developing once the plant attains its full size of around 60 centimetres high and wide. When the plant is harvested, the leaf stalks are removed from the stem, resulting in the familiar-looking wasabi rhizome so often depicted on wasabi products – imitation or otherwise.

Wasabi’s Health-Giving Properties

In addition to its renowned flavour, wasabi has long been prized in Japan for its anti-microbial and medicinal properties and is thought to have been part of the Japanese diet since pre-historic times. Wasabi is traditionally believed to aid in the prevention of food poisoning, and historically was an essential condiment at the tables of nobles and warlords alike.

An important study at Kennesaw State University, the first of its kind, has indeed confirmed what the Japanese have always known. Allyl isothiocyanate, an antimicrobial compound naturally present in wasabi, has been found to have strong antibacterial property and high potential to effectively control two of the major pathogens frequently involved in foodborne outbreaks, the dreaded E. coli O157:H7 and Staphylococcus aureus. Along with its unique flavour, the antibacterial property and potential to safeguard foods makes wasabi a promising natural edible antibacterial plant, which could be of significant interest to the food industry as they develop new and safe foods.

Other research into the medicinal properties of wasabi have confirmed the ability to lower inflammation, to prevent heart disease and inhibit certain types of colorectal cancer, to fight osteoporosis and even to aid weight loss (in mice, at least!). It would seem that we are only just beginning to explore the health-giving properties of this versatile herb.

Wasabi’s Unique and Volatile Flavour

The entire wasabi plant contains the volatile (readily evaporated) compounds that give wasabi its unique flavour, and all parts of the plant can be eaten. Wasabi paste is obtained by grating the rhizome, while the leaves, stalks and roots can also be chopped up and incorporated into a range of recipes.

Fresh wasabi grated on a sharkskin grater. Freshly-grated wasabi is slightly sweet.

Allyl isothiocyanate is one of the compounds responsible for wasabi’s pungency. As soon as any part of the fresh plant is cut or the cell walls disrupted, a reaction of the enzyme myrosinase causes this volatile compound to be released. The eye-watering, nose-clearing, hole-through-the-top-of-the-head effect of wasabi occurs as the isothiocyanates irritate the nasal membranes. You don’t even have to eat wasabi to feel its effects. As with onions, just cutting or grating the plant can bring tears to your eyes. With humans being the perverse creatures we are, the plant’s defense mechanism has become its most sought-after property.

Interestingly, a side effect of the myrosinase enzyme reaction is the production of glucose. In addition to its pungency, freshly grated wasabi is slightly sweet, as I found out for myself in October (2018) when I visited Japan’s best-known wasabi farm.

Click here to read Part 2 of this article: Daiō Wasabi Farm