We have a long history in Japan of using the natural materials around us to craft objects for everyday use. These have always been essential items, in keeping with our lifestyles and the climate and natural features of our surroundings. Such items are still crafted using the skill and ingenuity handed down by our predecessors. Yet nowadays, modern living, coupled with the ready availability of low cost synthetic materials, mean that the use of handcrafted household items has declined sharply.

To address this problem, the government passed the Densan (Traditional Industries) Act in 1974, which aims to support industries producing traditional crafts by offering financial assistance to those that meet the criteria. To meet the Densan criteria and be designated as ‘Traditional Crafts’, products should be used mainly in everyday life, largely handmade, crafted using traditional techniques and from traditionally used raw materials. Additionally, the industry should be traditional to its region. As of writing, 230 items Japan-wide have met these criteria and are officially recognised as Traditional Crafts.

In this series we take a region-by-region look at the unique features of these traditional crafts and the legacy of the skilled craftspeople who keep these precious skills alive.

Text : 中澤浩明 Hiroaki Nakazawa / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Traditional Crafts Series / Shizuoka Prefecture / Niigata Prefecture / Aichi Prefecture / Fukui Prefecture / Toyama Prefecture / Gifu Prefecture / Traditional Skills / Yamanashi Prefecture / Nagano Prefecture / Ishikawa Prefecture

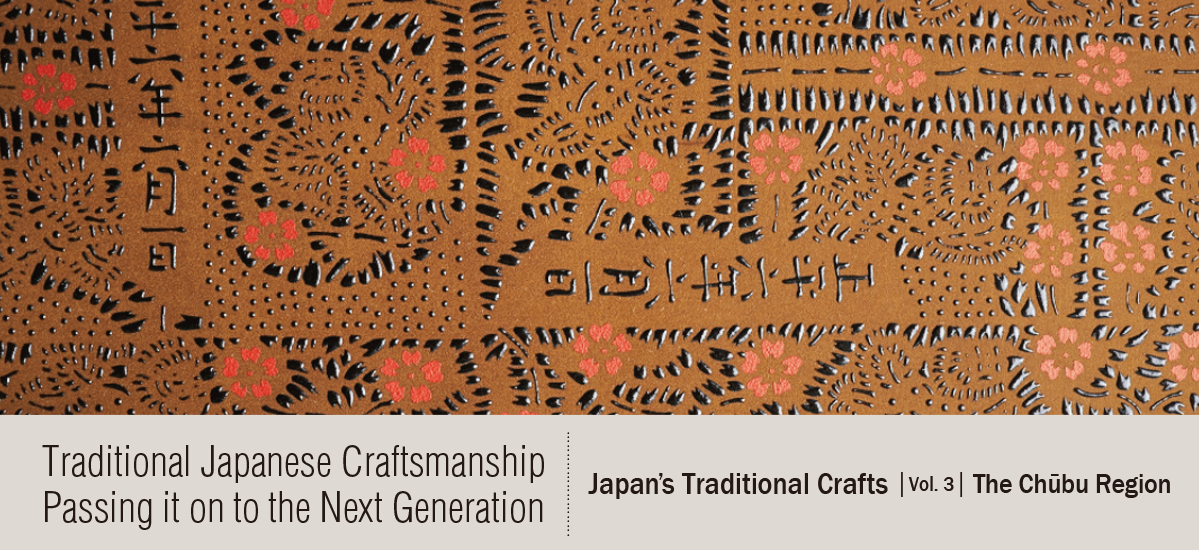

Features of the Chūbu Region – Simple Everyday Articles with Elegant Ornamentation

In areas of heavy snowfall along the Japan Sea coast such as the Hokuriku Region, farmers once occupied themselves through the long winters making the types of household articles that were indispensable to daily life. Since the Edo Period (1603 – 1868), with improvements in lifestyle and advancements in skills and technology, these everyday articles have come to be elegantly adorned with magnificent decoration.

Niigata Prefecture

Shiozawa Tsumugi Silk/Hon-Shiozawa Silk/Ojiya Chijimi Linen/Ojiya Tsumugi Silk/Tōkamachi-gasuri Textiles/Tōkamachi Akashi-chijimi/Uetsu Shinafu Cloth (listed also under Yamagata Prefecture)/Murakami Kibori Tsuishu Lacquerware/Niigata Shikki Lacquerware/Kamo Kiritansu Chests/Tsubame Tsuiki Douki Copperware/Echigo Yoita Uchi Hamono Knives/Echigo Sanjo Uchi Hamono Knives/Niigata/Shirone Butsudan Altars/Nagaoka Butsudan Altars/Sanjo Butsudan Altars

Most of Niigata’s woven textiles boast a very long history. Ojiya Chijimi ramie cloth, a national important intangible cultural property, is a puckered woven fabric designed to keep the wearer cool during hot weather. Ojiya Tsumugi is a linen-type cloth woven using the Ojiya Chijimi technique. Production began in the middle of the Edo Period (1603 – 1868). Shiozawa Tsumugi and Honshiozawa Tsumugi are silk fabrics manufactured using hemp weaving techniques passed down through the ages. Tōkamachi-gasuri and Tōkamachi Akashi-chijimi silk fabrics became popular from the end of the Edo Period through the Meiji Period. Tokamachi-gasuri is considered to have folk art qualities, while Tokamachi Akashi-chijimi is known for its refreshingly cool texture. Niigata is also known for the manufacturing of metal products, particularly sickles, pots and pans, saws, and chef’s knives. Tsubame Tsuiki Douki are copper pots and pans hammered into their three-dimensional shapes from a single sheet of copper. Echigo Yoita Uchi-hamono knives began with sword manufacture during Japan’s “Warring States” Period (c. 1467 – c. 1600). Niigata is second only to Kyoto with the number of government-designated traditional crafts. Other flourishing local industries include woodwork and lacquerware such as Murakami Kibori Tsuishu carved lacquerware, Kamo Kiri Tansu (Paulownia chests), and Niigata Shikki lacquerware, while the butsudan (Buddhist altar) manufacturing makes the most of the area’s splendid metalwork tradition.

Yamanashi Prefecture

Kōshū Suishō Kiseki Zaiku Crystal and Gemstone Carving/Kōshū Tebori Inshō Seals/Kōshū Inden Lacquered Deerskin

Kōshū Suishō Kiseki Zaiku crystal and gemstone carving are ornaments and accessories made from naturally-occurring crystals and gemstones from the mountains north of Kōfu City. Hand-polishing techniques were introduced from Kyoto during the late Edo Period (1603 – 1868). Kōshū Tebori Inshō hand-carved signature seals are manufactured using Japanese boxwood, water buffalo horn and crystals. Production took place throughout Yamanashi Prefecture during the late Edo Period. Kōshū Inden lacquered deerskin production thrived around Kōfu City in the late Edo Period, with wallets and drawstring purses being popular items. (Read the article on Kōshū Inden.)

Nagano Prefecture

Shinshū Tsumugi Silk/Kiso Shikki Lacquerware/Matsumoto Kagu Furniture/Nagiso Rokuro Zaiku Woodturning/Shinshū Uchi-hamono Knives/Iiyama Butsudan Altars/Uchiyama-gami Paper

Production of Shinshū Tsumugi silk was encouraged by all the domains in the Shinshū (Nagano Prefecture) region from the early Edo Period. Textiles were even shipped from here to Kyoto. Three separate lacquer techniques are used to produce Kiso Shikki lacquerware. Nagiso Rokuro Zaiku wood-turning, which began during the 1700s, features simple designs that bring out the natural wood grain. Matsumoto Kagu furniture-making started in the 16th century. It is highly valued as a folk craft. The Shinshū Uchi-hamono knife and blade industry is thought to have sprung up around sword manufacture connected to the Battle of Kawanakajima. A wide range of chef’s knives, sickles and other bladed tools is still produced. Iiyama Butsudan Buddhist altars have been produced in the temple town of Iiyama since the early Edo Period. Uchiyama-gami handmade paper is made from the bark of the mulberry tree. The bark fibres are bleached naturally in the snow, yielding a strong, durable product with a soft texture.

Gifu Prefecture

Mino-yaki Ceramics/Hida Shunkei Lacquerware/Ichii Ittōbori Woodcarvings/Mino-washi Paper/Gifu Chōchin Lanterns

Mino-yaki ceramics, produced in Tono, which developed during the Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1568 – 1600) alongside the growing popularity of the tea ceremony, became Japan’s largest ceramics and porcelain industry. Production of Hida Shunkei lacquerware began during the early Edo Period. The clear lacquer brings out the beauty of the wood. Each Ichii Ittōbori woodcarving is sculpted from a single piece of yew wood, leaving the wood unpainted to bring out its natural characteristics. Mino-washi paper is highly valued for its even texture. Its uses include shōji screens and archival documents. Gifu Chōchin paper lanterns are widely used during the summer O-bon festival, as well as for adding a cooling touch around the home on a hot summer evening.

Shizuoka Prefecture

Suruga Takesensuji Zaiku Bamboo Crafts/Suruga Hinagu Doll Accessories/Suruga Hina Ningyo Dolls

Suruga Takesensuji bamboo crafts became widespread during the Edo Period when they were sold to travellers as sweet containers and cages for crickets. Production of Suruga Hinagu doll accessories was well established by the 16th century. Mass production of Suruga Hinagu was made possible thanks to a division of labour system of the different processes such as woodwork, lacquer work and metalwork. Production of Suruga Hina Ningyo began as dolls dressed in the costumes of the late Edo Period, and moved to the production of dolls for the Boys’ and Girls’ Festivals.

Aichi Prefecture

Arimatsu Narumi Shibori Tie-Dyeing/Nagoya Yūzen Textiles/Nagoya Kuromontsuki-zome Kimono Dyeing/Akazu-yaki Pottery/Seto Sometsuke-yaki Porcelain/Tokoname-yaki Ceramics/Nagoya Kiri Tansu Chests/Mikawa Butsudan Altars/Toyohashi Fude Calligraphy Brushes/Okazaki Sekkōhin Stonemasonry/Owari Shippō Enamel/Sanshū Onigawara Kougeihin Tiles/Owari Butsugu Buddhist Equipment

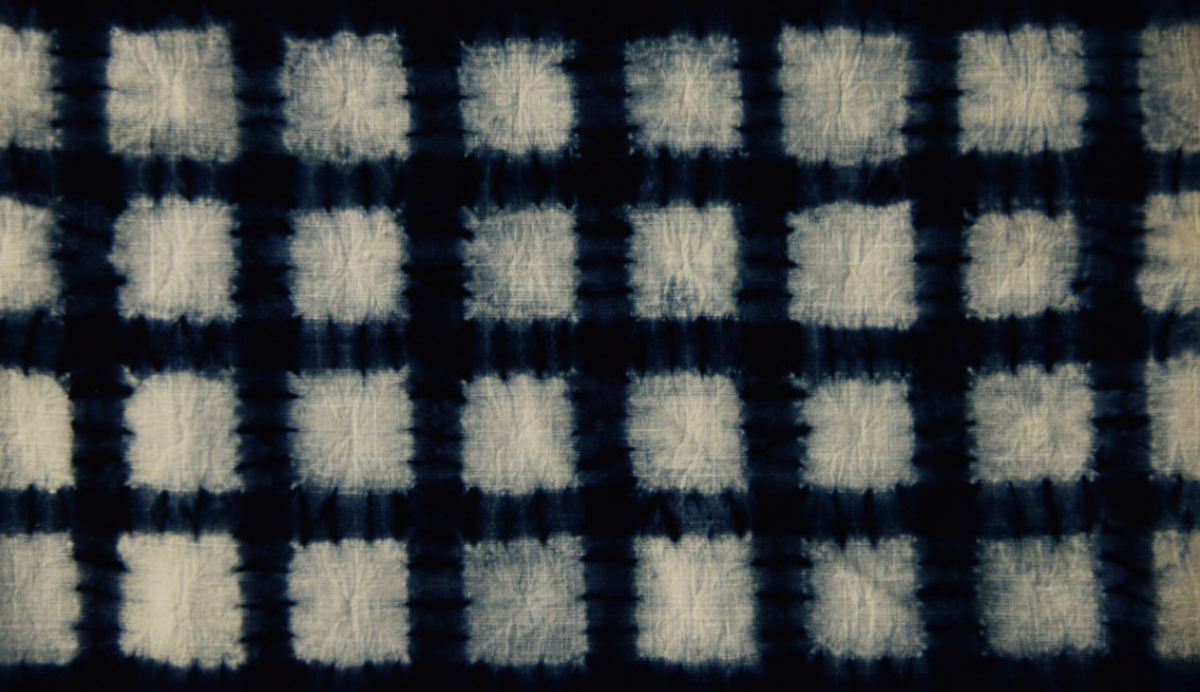

Arimatsu Narumi Shibori tie-dyeing is a technique handed down from the early Edo Period (1603 – 1868). Production expanded after exclusive sales rights were granted by the local domain. Nagoya Yūzen weaving techniques were taught by Kyoto weavers during the mid-Edo Period. Jet-black Nagoya Kuromontsuki-zome dyeing began as a technique for applying clan insignia to banners and streamers. In this famous pottery region, Tokoname-yaki ceramics is said to originate in the late Heian Period (794 – 1185). The red colour of the pottery comes from the iron content of the clay. The Akazu-yaki pottery technique was established during the early Edo Period. The industry prospered as the official kiln of the Owari Domain. Seto Sometsuke-yaki porcelain developed rapidly in the second half of the Edo Period after porcelain techniques were introduced from Kyūshū. A characteristic is the fine shading in blue, applied to white porcelain. The luxurious Nagoya Kiri Tansu paulownia chests are wider than chests produced in other regions and decorated with gold and silver leaf. Manufacture of Nagoya Butsudan and Mikawa Butsudan Buddhist altars developed during the early to mid-Edo Period. Owari Shippō enamel ware is made by applying enamel to a metal base to form patterns for vases and ornamental plates. Sanshū Onigawara Kougeihin refers to a wide range of items such as demon masks and ridge-end roof tiles, as well as other types of exterior ornamentation, made using kiln-fired tile manufacturing techniques.

Toyama Prefecture

Takaoka Shikki Lacquerware/Inami Chōkoku Carvings/Takaoka Dōki Copperware/Echū Washi Paper/Shōgawa Hikimono Kiji Woodcraft/Echū Fukuoka no Suge-gasa Hats

Both Takaoka Shikki and Takaoka Dōki started in the early Edo Period (1603 – 1868). Takaoka Shikki lacquerware features trays and boxes made in three distinct styles. Takaoka Dōki copperware achieved renown when it was exhibited at expositions around the world during the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912). Items range from small household items to temple bells and statuary, featuring production techniques such as polishing, metal carving and inlaying. To create Inami Chōkoku wood carvings, highly skilled carvers use up to 200 different chisels and knives to create finished pieces such as lions’ heads, and ranma transom panels. Shōgawa Hikimono Kiji woodcraft produces household items such as trays and bowls, made to bring out the beauty of the annular rings of the wood. The craft started towards the end of the Edo Period. Production of Echū Fukuoka no Suge-gasa hats was promoted by the Kaga Domain during the Edo Period. The craft was officially designated as a traditional craft in 2017.

Ishikawa Prefecture

Ushikubi Tsumugi Silk/Kaga Yūsen Textiles/Kaga Nui Embroidery/Kutani-yaki Pottery/Wajima Nuri Lacquerware/Yamanaka Shikki Lacquerware/Kanazawa Shikki Lacquerware/Kanazawa Butsudan Altars/Nanao Butsudan Altars/Kanazawa Haku Gold Leaf

Ushikubi Tsumugi silk textiles, produced in Hakusan City, originated in the mid-12th century in Ushikubi Village, at the base of Mt. Haku. Kaga Yūzen was started by artists from Kyoto during the mid-Edo Period. This elegant dyed textile features designs of landscapes, flowers and birds, and colour gradation. Kaga Nui embroidery techniques have been handed down since the early Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573). The works feature beautiful patterns embroidered in multicolored silk thread. Kutani-yaki pottery, revived after having once been discontinued, features figures of flowers, birds and landscapes, using five specific colours. Wajima-nuri lacquerware originated during the early Muromachi Period. One of the characteristic methods is the adding of gold inlay to patterns etched into the pieces after they have been lacquered. Yamanaka Shikki lacquerware originated during the Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1568 – 1600). A range of finishes includes clear lacquer that allows the wood grain to show through, and highly lacquered black and vermilion pieces with gold maki-e designs. Kanazawa Shikki lacquerware developed during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) as part of the Kaga Domain’s strategy to promote industrial arts. The pieces feature elegant gold maki-e designs. Kanazawa Butsudan Buddhist altars feature ornate gold leaf and lacquer work, made possible with the support of the wealthy Kaga Domain. Kanazawa-haku gold leaf production began after the Meiji Restoration (1868), with a monopoly on the production of gold leaf. Sheets of gold leaf are beaten to a thickness of as little as one to two ten thousandths of a millimetre.

Fukui Prefecture

Echizen-yaki Ceramics/Echizen Shikki Lacquerware/Wakasa-nuri Lacquerware/Echizen Tansu/Echizen Uchi Hamono Blades/Echizen Washi Paper/Wakasa Menō Zaiku Agate Work

Echizen-yaki ceramics are simple household items made using ceramic and porcelain techniques passed down since the Heian Period (1185–1333). Beautiful maki-e gold designs are a feature of Echizen Shikki lacquerware. A wide range of products are made, from bowls and stacked boxes, to trays and chopsticks. Wakasa-nuri lacquerware features lacquered tableware decorated with slivers of seashell, or gold and silver leaf. Echizen Tansu are imposing, lacquer-coated chests made of Japanese zelkova and paulownia, and decorated with iron fittings. Echizen Hamono are handmade chefs’ knives, sickles and other farming tools. Used for the writing of sutras during the Nara Period, Echizen Washi paper is now used for a wide range of applications, from fusuma screens to ceremonial paper. Wakasa Menō Zaiku products include Buddhist statues, incense holders, sake cups and jewelry made from carved and polished agate.