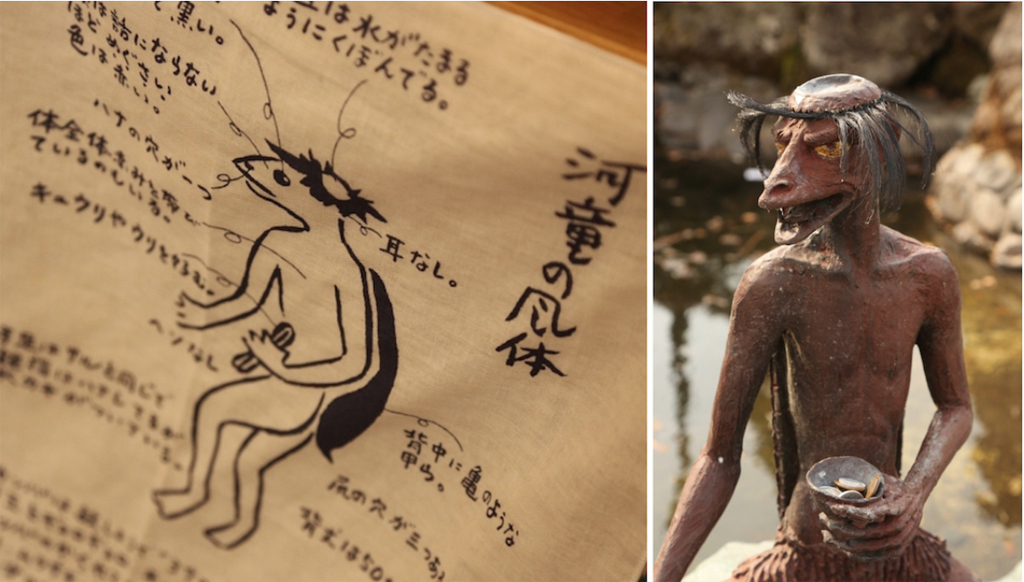

Japanese folklore is populated by a rich array of mystical beings, all of whom (including the zashiki-warashi, a child-like house spirit, and the kappa, a water goblin) appear in the renowned Tōno folktales. These tales were recorded in the Tōno Monogatari (The Legends of Tōno), a treatise published in 1910 by folklorist Kunio Yanagita, who is now remembered as the founder of Japanese folklore studies. Passed down via an oral tradition that spans generations, the Tōno folktales continue to come to life in the local dialect thanks to a dedicated group of storytellers. Writer Takashi Sasaki visited Tōno and met to Sanomi Kudō, president of the Tōno Folktale Storytellers Association (the Tōno Monogatari Kataribe no Kai).

Text : Sasaki Takashi / Photos : 平島 格 Kaku Hirashima / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Kunio Yanagita / Kisen Sasaki / Ronald Morse / Iwate Prefecture / Storytellers / Folktales / Legends of Tono / Kappa / Kappabuchi

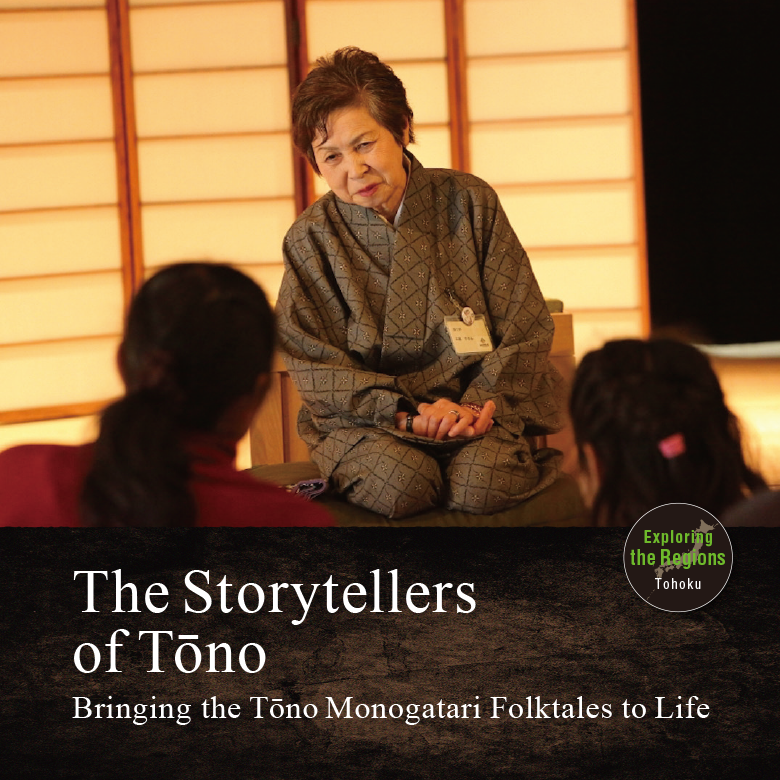

Local Treasure Narrated in the Local Dialect

The Tōno folktales were once told and retold around the hearths of the households of this rural area, and were passed down in the local dialect through an oral tradition that spanned generations. However, ever since the economic boom that began after the Second World War, Japan has become increasingly saturated with manufactured distractions and entertainment, and children no longer pester their parents or grandparents to tell them a story.

Concerned about the potential loss of the region’s oral history, a group of women storytellers is actively working to preserve Tōno’s oral folklore tradition. Born in 1944, Sanomi Kudō grew up hearing these tales from her mother, a busy farmer, and from her elderly grandfather, who enjoyed time spent relaxing by the family hearth. However, Kudō san realised with a shock one day that she had never related a single one of these traditional stories to her own daughter.

It wasn’t until after raising her own children, when she went back out to work as a bus tour guide at the age of forty-five, that Kudō san started telling Tōno’s traditional tales in public. The time was the late 1980s, when tour buses featured the latest karaoke and video amusements to entertain sightseers. “It seemed such a pity to have come all this way only to spend the trip watching videos and singing karaoke, something they could do anywhere!” With this thought, Kudō san decided to share some of the faintly-remembered folktales of her childhood. She was pleasantly surprised at how well they were received by the passengers aboard the bus.

Realising how Tōno-ben, the local dialect, imbued these local folktales with a special value all of their own, Kudō san recruited some of her friends and began attending the Tōno Monogatari Kenkyūjo (Tōno Folktale Research Centre), where she studied under a mentor for four years. Then, in 1999, she set up in a vacant shop premises in the town of Tōno, and began sharing the folktales with visiting tourists.

“Kappabuchi” – a Tōno Folktale

Long, long ago, in a stream behind the home of a family known as the Tsuchibuchi no Shinya family, there was a deep, deep pool. One hot summer’s day, the children of the house decided to take their horse down to the pool to cool its feet, and off they all went, laughing and skipping.

Suddenly, a kappa appeared and tried to drag the poor horse under the water. The horse got such a fright that it reared up and raced back to its stable with the startled kappa still holding on for dear life! Now it was the kappa’s turn to be frightened, and in its panic it tipped over the horse’s feed trough and scrambled underneath it to hide.

Everyone in the house was surprised to hear such a commotion. “Aren’t they back a bit early?” they wondered. “And why is the horse kicking up such a fuss?” Curious, the whole family crowded around and peered into the stable just in time to see a pair of tiny hands poking out from under the upturned wooden trough. They lifted up the trough and, lo and behold, there was the kappa!

By now all the villagers had gathered around to see what was going on. “This kappa is always up to mischief!” they clamoured. “We should kill the little villain!” But then they saw that the kappa, with its hands clasped together, was pleading for its life.

The master of the house took pity on the little fellow. “If we let you go, promise not to do any more harm!” he demanded. The kappa did as it was told and left at once, going to live in a pool in faraway Aizawa.

And that was that. Now it’s time for bed!

(A Romanized version of this folktale, as told in the local Tōno dialect, can be found at the end of this article).

A World of Mystery and Strange Apparitions Brought to Life by Storytellers

Kudō san says that Tōno-ben is a dialect that needs to be spoken, joking that it makes no sense when it’s written down. And she has a point. When the stories are spoken aloud they come alive with a magic of their own, resonating in the hearts of the listeners and soothing the soul. Accompanied by the storyteller’s gestures and facial expressions, unfamiliar words in the local dialect are no barrier to understanding the overall story. The skill of the storyteller and the charm of the Tōno dialect combine to transport the listener to a long-ago world where mischievous mythical creatures such as kappa, zashiki-warashi and tengūmeddled with the affairs of humans.

There were no textbooks at the Tōno Folktale Research Centre when Kudō san studied to become a storyteller. Instead, the students were taught only the plot outlines of the various stories by their mentors. This is an oral tradition and in order to become storytellers themselves, the students had to listen intently as the folktales were recounted.

As with any oral tradition, there are variations in the way individual storytellers narrate the same tale, sometimes with slightly different details in the plot or setting. What’s more, as Kudō san explains, even within the Tōno dialect there are differences. “I grew up on the outskirts of Tōno in a village called Tsukimoushi. Mrs Gotō grew up in Tōno itself, while Mrs Okudera grew up in Morioka and moved here when she married into a local family. People from the big cities, hearing the three of us speak, might just hear the Tōno dialect and think we all sound the same, but we don’t. We each have a slightly different manner of speaking, and a slightly different accent.”

Every Tōno folktale ends with the words, “Dondo hare”. This expression harks back to the time when rural folk would gather around the hearth in the evenings, fashioning hand-crafted items and telling stories. Dondo refers to the bits of straw and debris that would drop into one’s lap while making these items, and “hare” in the local dialect means “brush off”. “Dondo hare” conveys the idea that both the evening’s work and the story have drawn to a close. It’s time to brush the straw off your lap and go to bed.

Rustic Scenery Perfectly Suited to Tōno’s Traditional Tales

“The Legends of Tōno” by Kunio Yanagita

Published in 1910, the “Tōno Monogatari” (translated into English by Ronald Morse as “The Legends of Tono”) is the masterwork of folklorist Kunio Yanagita and a significant contribution to the development of folklore study in Japan. Written in collaboration with local Tōno novelist and folklorist Kizen Sasaki, the anthology comprises a hundred and nine folktales. The collection covers a wide range of themes, from stories of ghosts, witches and goblins to tales of the bizarre and legends concerning religious rituals.

Tōno Monogatari no Kan (Tōno Folktale Museum)

At the Tōno Monogatari no Kan (Tōno Folktale Museum) visitors can enjoy a range of activities such as listening to folktales told by official storytellers in the Tōno-za (Tōno Theatre); experiencing the world of folklore in the Monogatari Kura (Legend Storehouse); or visiting the Kunio Yanagita Memorial Hall in the former inn where the famous folklorist would stay when he was in Tōno. There is also a restaurant and gift shop on site.

Address: 2-11 Chūō Dōri, Tōno City, Iwate Prefecture.

Hours: 9:00 am – 5:00 pm (last entry at 4:30 pm).

Closed: Open all year round (may close periodically for maintenance in mid-February).

Admission: Adults: 510 yen. High school students and younger 210 yen.

Access: About 500 metres from Tōno Station, or around 8 minutes on foot.

Parking: 40 spaces.

Phone: 0198-62-7887

Web: https://tonojikan.jp/ml/spot01/tono-folktale-museum/

(Romanized version of the folktale as told in the local Tōno dialect.)

Tōno Monogatari: Kappabuchi

Mugasu atta zumo na. Tsuchibuchi no Araya to yū ie no ura ni fukai fuchi ga atta do. Aru natsu no atsui hi, sono ie no wagemono ga umakko no ashi o hiyashite yarō to fuchi e tsurete itta ga, sono manma asobi sa itte shimatta do. Shitaba, kappa ga dete kite, umakko, fuchi sa hipparikomō to shitan da do.

Uma wa tamagete, gyaku ni kappa o hikizutta mama, umaya sa tobikonda do. Kondo wa kappa no hō ga tamagete, uma no fune gappari hikkurigete, sono naka sa kakureta do.

Ie no hitotachi wa, “Nantara uma sawagu be, konna ni hayagu kaette” to, fushigigatte umaya o nozoite mita do. Shitaba, uma no fune kara pekko na tekko mieta do. Akete mitakke kappa datta do.

Atsumatte kita mura no hitotachi wa, “Kono kappa, itsumo itazura shite, roku de nē gara koroshite shimē” tte itta kedo, hodadomo, yoku mitara, sono kappa wa tekko awasete itatta do.

Kono ie no aruji wa, mujo ya na to omotte, “Kore kara wa, koko de itazura sunna yo” tte, yurusu koto ni shitan da do.

Kappa mo yū koto kiite, soko kara tōku hanareta Aizawa no fuchi no hō sa itte shimattan da do sa.

Dondo hare.