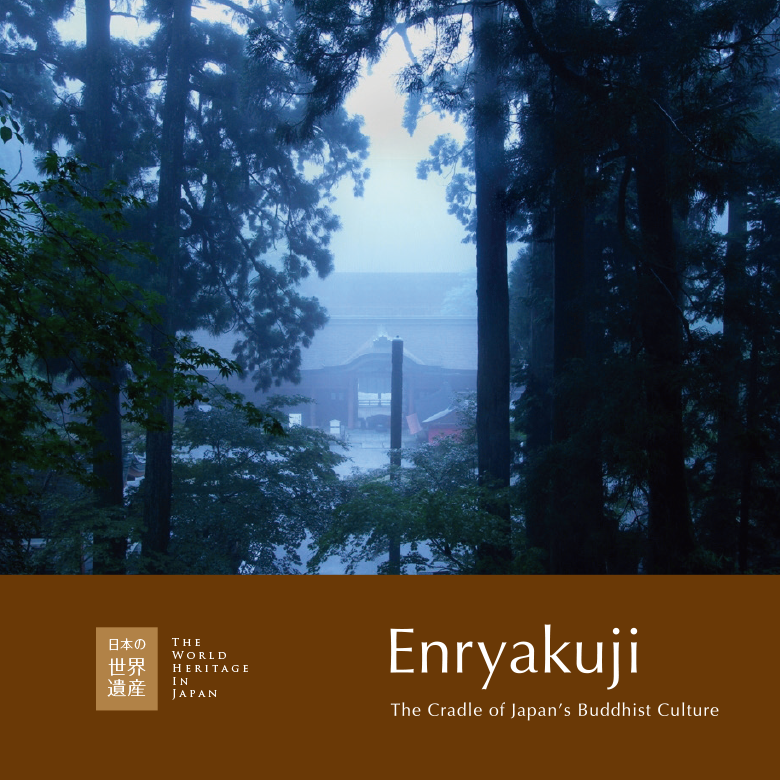

Over 1200 years ago, a visionary young Buddhist monk decided to found a monastery atop Hieizan, the sacred mountain presiding over the city of Kyōto. The monastery flourished to become one of feudal Japan’s most powerful and influential centres of religion and culture; so powerful that Hieizan and all who lived there suffered the wrath of ruthless samurai warlord, Oda Nobunaga, almost seven hundred years later. Now, in more settled times, Hieizan and the temples of the Enryakuji monastery form part of the “Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto” UNESCO World Heritage Site, and remain an important centre of Tendai Buddhism.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photos : 谷口哲 Akira Taniguchi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Enryakuji / Saichō / Shiga Prefecture / Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto / Japan World Heritage / Kyōto / Buddhism / World Heritage Sites / Hieizan

A New Sect to Challenge the Buddhist Establishment

The sprawling Enryakuji temple complex began with the construction of just one small temple hall in 788, when the monk Saichō determined that he would establish a monastery on remote Hieizan (Mt Hiei) on the north-eastern edge of what is now the city of Kyōto. This was a fortuitous location, as Hieizan was considered a sacred mountain that protected the old capital from the inauspicious north-eastern direction. Saichō’s temple, which he named “Ichijō Shikan-in”, occupied the same spot as the present-day Konpon Chūdō hall, now the main temple hall of Enryakuji.

Saichō was born in 767, in present-day Shiga Prefecture. He entered the priesthood at a young age, and was ordained as a Buddhist monk at Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara, at the age of just nineteen. After his ordination he secluded himself on Hieizan, which stands between Kyōto and his birthplace of Shiga, and continued his studies and ascetic training on the mountain. In 804, at the age of thirty-eight, Saichō travelled to China on the same mission as Kūkai, the famous monk who founded the Shingon sect. After studying the doctrines and principles of China’s Tiantai Buddhism, he returned to Japan bearing precious Buddhist sutras. Once back at Hieizan, Saichō set about establishing a Tendai (the Japanese pronunciation of Tiantai) sect on Kyōto’s sacred mountain.

Saichō knew that in order to spread the teachings of Tendai Buddhism, he would need an excellent training programme for his monks. At the time, Buddhist ordinations could only take place at three government-sanctioned ordination halls. These were located at Tōdaiji Temple in Nara, Shimotsuke Yakushiji Temple in Tochigi (now a ruin), and Chikuzen Kanzeon-ji Temple in Fukuoka, Kyūshū. Saichō repeatedly petitioned the imperial household for permission to establish an independent ordination process, separate from the old, established Buddhist sects, so that monks who studied at his Hieizan monastery could be ordained there.

When Saichō died in 822 at the age of fifty-six, his new, independent school of Buddhism had yet to be officially recognized. However, despite vehement opposition from the Nara schools, he had never given up on his conviction. His greatest wish was fulfilled seven days after his death, when imperial permission was granted to ordain monks into the Tendai school on Hieizan. In the following year, Emperor Saga granted permission for Saichō’s monastery to be called Enryakuji, “Enryaku” being the name of the imperial era in which the monastery was first established.

The foundations were thus laid for the Tendai school to grow and prosper for hundreds of years to come. In 866, one hundred years after his birth, Saichō was granted the posthumous Buddhist name of Dengyō Daishi, becoming the first Buddhist monk to receive the title, “Daishi”, denoting his importance as a priest and teacher.

The Rise and Fall, and Rebirth of Enryakuji

The traditional Buddhist schools of Nara that had been so strongly opposed to the establishment of the Tendai sect declined during the Heian Period (794 – 1185), while the new sects of Tendai and Shingon Buddhism became mainstream. Tendai priests such as En’nin and Enchin were instrumental in expanding the Tendai school’s influence, gaining the trust of the aristocracy and receiving grants of land for temples, thus ensuring the financial stability of the new sect.

However, after their deaths, the respective followers of these two priests came into conflict with each other and established rival branches. While En’nin’s followers remained at Enryakuji on Hieizan, Enchin’s followers based themselves at Onjōji Temple, at the base of the mountain in Shiga Prefecture. The rivalry between the two groups led to armed conflicts as the temples developed their own armies of warrior monks. These armies eventually became powerful and widely feared, infamously marching to the imperial palace to make demands of the government and, on occasion, running rampant in the streets of Kyōto.

Despite the public chaos caused by the warrior monks, Hieizan produced many renowned priests who branched out towards the end of the Heian Period and through the Kamakura Period (1185 – 1333), and established six new schools of Buddhism. These were the Yuzu Nembutsu school, the Jōdo school, the Rinzai school, the Sōtō school, the Jōdo Shinshū school, and the Nichiren school. The development of these schools, which collectively became known as the “new Buddhism of the Kamakura Period”, broadly aligned with Saichō’s idea of “shishū sōshō”, or four types of Buddhism: Tendai, Esoteric, Zen, and Vinaya, which he had brought to Hieizan and tried to embrace within one school. Because these new schools developed out of Tendai, Hieizan is thought of as the cradle of Buddhism in Japan.

Ominously, Hieizan’s days as a centre of power were numbered. Due to the threat posed by its standing army, Hieizan increasingly became the target of military attacks through the 14th century. In 1571, samurai warlord Oda Nobunaga invaded with an army of thousands, slaughtering the inhabitants of the mountain and burning the temples of Enryakuji to the ground. However, Nobunaga’s successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi granted permission for the monastery to be rebuilt, enabling the light of Buddhism to burn once more on Hieizan.

After the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate in Edo (Tokyo) in 1603, first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu enlisted the services of Tenkai, the monk who had helped rebuild Enryakuji. His purpose was to establish a new temple to protect Edo, just as Enryakuji was believed to protect Kyōto. To improve the energy from the inauspicious north-east, Kan’ei-ji Temple was constructed in Ueno, north-east of Edo Castle, on a hill named Tōeizan. Ieyasu’s new temple was intended to mirror Enryakuji in the protection it afforded the new capital. Tōeizan means “Hieizan of the East” and Kan’ei-ji was named after the Kan’ei imperial era during which it was founded, just as Enryakuji had been named for the Enryaku era.

Tendai’s Inclusive Philosophy and Challenges to the Limits of Human Endurance

Tendai Buddhist doctrine, based on the Lotus Sutra and the One Vehicle doctrine, holds that all human beings are innately enlightened. In addition to the Tiantai teachings, Saichō also brought back from China other elements of Buddhism including Zen, the esoteric Mikkyō, and the Vinaya School, which he incorporated into Tendai Buddhism. To this he added the intonation of nembutsu (prayers to the Buddha). With this all-embracing outlook, Tendai monks went forth to preach their doctrine for the salvation of humanity, the prosperity of the nation, and the construction of a “Land of the Buddha”.

The promotion of a comprehensive, nuanced approach to Buddhism that was not limited by any single doctrine or way of thinking, nor by the beliefs of just one sect, is an important characteristic of the Japanese Tendai school. The Lotus Sutra, the scripture believed to contain the final teachings of the Buddha, is the main scripture of Tendai, but importance is also placed on scriptures such as the Amida Sutra and the Dainichi Sutra.

In accordance with the Tendai principle of ichinen-sanzen, which holds that each and every moment contains the entirety of existence, Tendai teaches that the Buddha resides within all people and things. Accordingly, there are no specific rules governing what type of Buddhist imagery should be used as objects of worship at the various Tendai temples, and imagery therefore varies depending on the history and circumstances of each location.

Another of the features of Tendai Buddhism is its harsh and demanding ascetic practices. Particularly demanding among these is jūni rōzan, where monks train in seclusion for twelve years. Monks undergoing jūni rōzan begin the day at two in the morning with a prayer service, make offerings at Tendai founder Saichō’s mausoleum morning and night, and practice the ritual of gotai-tōchi (full body prostration) three thousand times each day as a way of perceiving the nature of the Buddha.

Another ascetic practice, the sennichi kaihō-gyō, in which monks devote one thousand days over the course of seven years to walking (and running) a route around Hieizan and its environs, began during the Heian Period (794 – 1185). During the fifth year of the kaihō-gyō, on the 700th day of walking, the practitioner begins a dangerous nine-day ritual fast, during which no food, water or sleep are allowed. In the past, monks who failed at this point were prepared to kill themselves, and carried a rope and short sword for that purpose. Elements that symbolise these items are still carried by monks attempting the sennichi kaihō-gyō in modern times.

Enryakuji – The World Heritage Site

Enryaku-ji is a sprawling temple complex made up of around 150 temple buildings spread over three sectors known as the Tō-dō (Eastern Pagoda), the Sai-tō (Western Pagoda) and the Yokawa areas. The property itself is almost 500 hectares of mountain, with a buffer zone double that in size. Each of the three areas has developed independently of the others, and has its own main temple building.

The Tō-dō sector is the birthplace of Enryaku-ji and the location of the Konpon Chūdō temple hall, constructed on the site of Saichō’s original Ichijō Shikan-in temple. A statue of the Buddhist deity, Yakushi Nyōrai, said to have been carved by Saichō himself, is enshrined here at Konpon Chūdō. Another important building in the Tō-dō sector is the Kaidan-in ordination hall. Designated as an important cultural asset, the Kaidan-in was originally built by Saichō’s disciples after his death, and was rebuilt in the early Edo Period (1603 – 1868).

The Sai-tō area developed around the Shaka-dō hall, constructed by Saichō’s successor Enchō, the second head priest of Enryaku-ji after Saichō’s death. The original building was burned to the ground in Oda Nobunaga’s attack on Hieizan and its replacement, the current Shaka-dō hall originally stood at Onjōji Temple, at the base of the mountain in Ōtsu city, Shiga Prefecture. It was relocated here by Toyotomi Hideyoshi when Enryakuji was rebuilt. Although not original to this site, the Shaka-dō is the oldest building at Enryakuji. The Jōdo-in hall, which houses Saichō’s mausoleum and is the most sacred site on the mountain, is located nearby.

The Yokawa area is around four kilometres north of the Sai-tō area. This is where Saichō’s successor, En’nin secluded himself. Yokawa Chūdō, the area’s main temple hall, houses the Sho Kannon Bosatsu, a wooden statue of the Bodhisattva of Compassion said to date back to the Heian Period. The nearby temple of Ganzan Daishi-dō is said to be the birthplace of omikuji fortune slips, the strips of paper often seen tied to wires and branches of trees at temples throughout Japan.

Enryakuji, a World Heritage Site encompassing an entire mountain and its many precious buildings, is unique by world standards. It is hoped that, unlike Kyōto’s other cultural properties, the preservation of Enryakuji takes into account not only the architectural and aesthetic value of the site, but also seeks to maintain the traditions of the ascetic mountain training associated with Enryakuji, as well as the dignified solemnity of this sacred site.