The magariya is a traditional farmhouse design found in various parts of Japan. Meaning ‘bent house’, the name derives from the L-shaped floor plan created by having the horse stables and workshop attached at a right-angle to one end of the main house.

Text : Sasaki Takashi / Photo : 平島 格 Kaku Hirashima / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Nambu Magariya / Iwate Tono

Magariya – Combining Main House and Stables Under the Same Roof

Because many magariya can still be found in the Northern Honshū prefectures of Iwate and Aomori (once the feudal domain of the Morioka clan and known as the Nambu Domain in the early part of its history), these L-shaped dwellings are generally referred to as ‘Nambu magariya’. However, this style of farmhouse construction can be found extensively across areas of north Kantō (the prefectures immediately north of Tokyo) and throughout the entire Tōhoku region of northern Honshū. Not all farmhouses with attached stables are built in an L-shape. Those with their stables constructed in line with the main dwelling are called sugoya, or ‘straight houses’.

In order to take a closer look at these lovely old houses, we visited Tōno Furusato Village on the outskirts of Tōno, the area famous for its oral folktale history. This replica village contains one sugoya and six magariya farmhouses from the surrounding area that have been relocated here and restored to recreate a traditional mountain village. Local retired folk known as Maburitto (‘custodian’ in the local dialect) are stationed in each of the farmhouses to maintain local traditions and share their knowledge with visitors.

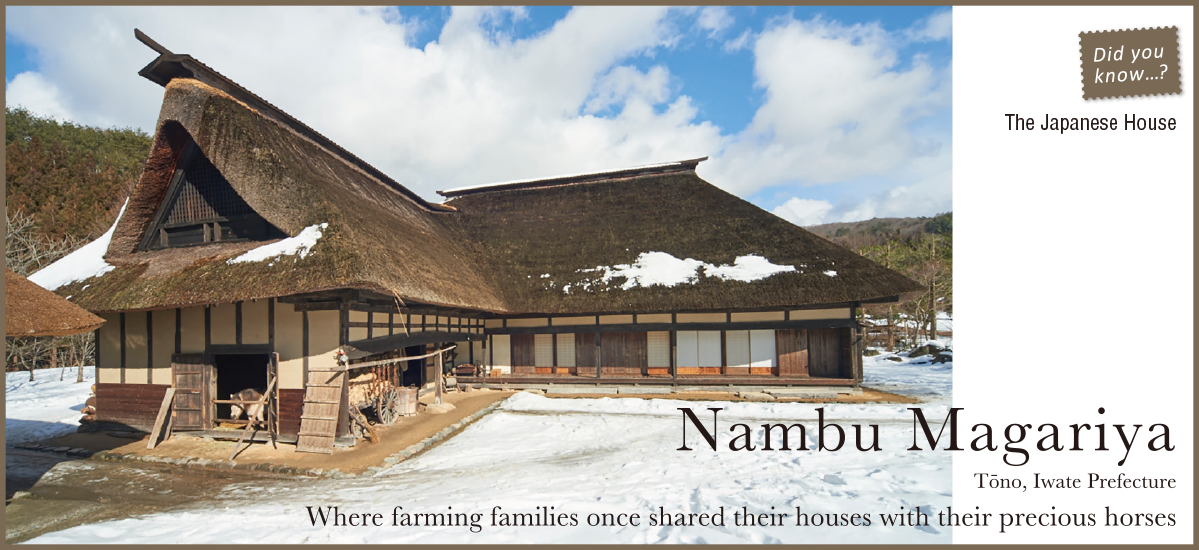

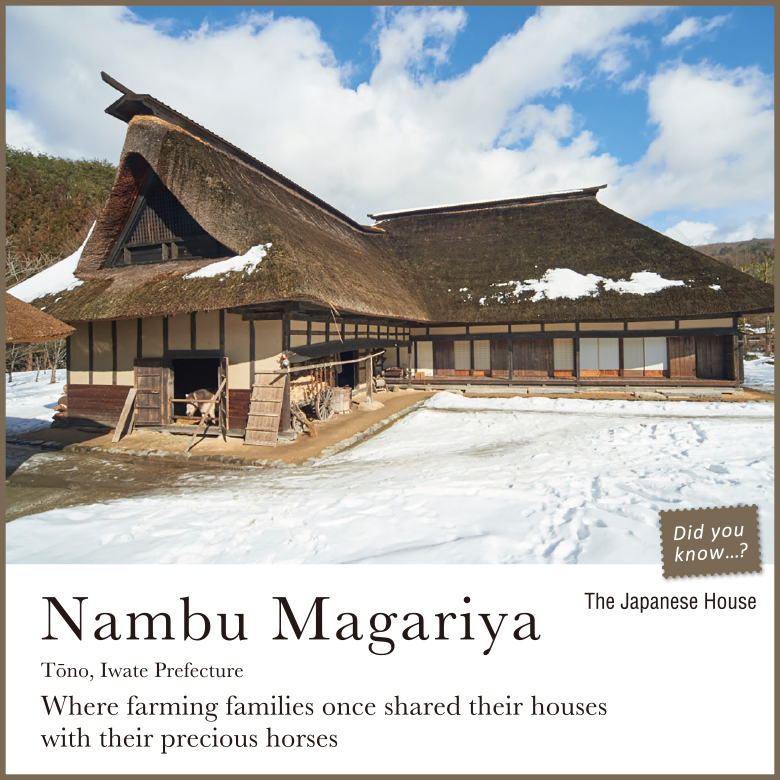

Standing in front of an actual magariya, one is immediately struck by the sheer size of the dwelling. Ōnodon, the magariyashown in the photo at the top of this article, has a total ground floor area of 280 square metres. In addition to this, there is an extensive upper floor in the roof space, which was once used for raising silkworms. The height of the ridge beam at the top of the roof is around seven metres.

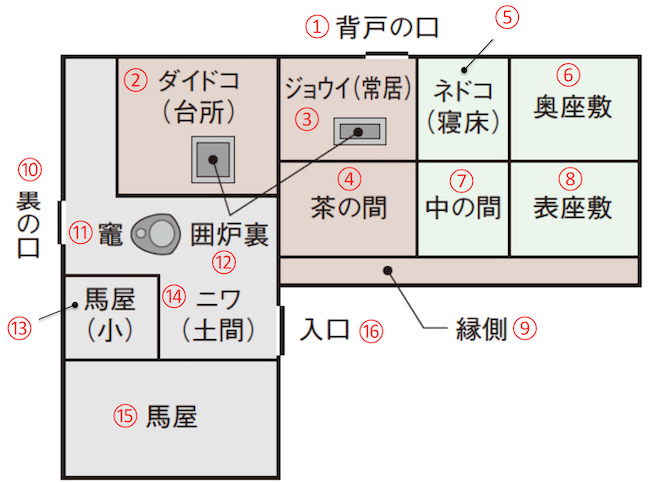

Typical Magariya Layout

① Seto-no-guchi – rear entrance; ② Daidoko – timber-floored room; ③ Jōi – timber-floored family room; ④ Chanoma – timber-floored living room; ⑤ Nedoko – sleeping space; ⑥ Oku-zashiki – rear reception room; ⑦ Naka-no-ma – middle room; ⑧Omote-zashiki – front reception room; ⑨ Engawa – verandah; ⑩ Ura-no-guchi – back door; ⑪ Kamado – cooking stove; ⑫ Irori – sunken hearths; ⑬ Umaya – (small) horse stall; ⑭ Niwa/doma – earth-floored utility space; ⑮ Umaya – horse stall; ⑯ Iriguchi – main entrance

People and Horses Under the Same Roof – a Perfect Response to the Long and Harsh North Country Winters

“It wasn’t until sometime after the war that rice could be grown in this area”, says Sakae Fujita, chairman of the Maburitto Association. “Before that, families earned a living raising silkworms, making charcoal and breeding horses.”

Fujita san was born in 1928 in nearby Tsukimoushi, a village on the outskirts of Tōno. He was raised in a thatched roof magariya, where he and his family lived until their home was destroyed in a fire that engulfed his village around sixty years ago.

The unique design of the magariya was a response to the long, harsh winters of the Tōhoku region. Fujita san explains that this L-shaped structure combining farmhouse and stable was the optimal design for keeping the stables warm and allowing the family to keep close watch over their horses.

The earth-floored space in the middle of the magariya is referred to as the doma or niwa. This covered workshop and cooking area is where the kamado, a large wood-fired clay cooking stove, is located. The heat from the kamado warms the stables and, in the absence of a chimney, its smoke escapes through an open gable in the roof. Behind the doma is the daidoko, a timber-floored room with an irori (hearth) sunk into the floor. Seated at the back of this hearth in the yokoza position traditionally reserved for the head of the household, the master of the house had a direct view onto the stables.

Fujita san demonstrates how the master of the house might have once looked across to the horses thinking, perhaps, “Oh, you seem a bit down this morning, let’s mix some rice bran in with your hay”.

Fujita san still has vivid memories of one time before the war when his two-year-old horse fetched the princely sum of six hundred yen at the autumn horse fair. Although difficult to convert into today’s currency, this would be the rough equivalent of around three thousand US dollars. His family was so thrilled that they added the stately suffix of “Sangō” to his given name. Episodes like this show the high esteem the people of Tōno had for their horses in days gone by.

Magariya farmhouses hold unforgettable memories for Kazuko Nitta, the other Maburitto custodian that we met. Born in 1952, Nitta san grew up in an ordinary house but her maternal grandparents lived in a magariya. The warm, spacious doma area was the perfect playground for children. In winter, she and her cousins would always gather to play at their grandparents’ magariyaafter school and on days off.

“Our father was so worried that us girls would never leave home that he even bought a television for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics”, she laughs. “He wanted us to see that there was more to the world than just our village”.

Under their blanket of winter snow, these traditional magariya farmhouses are crammed with ingenious design features that allowed people and their beloved horses to weather Tōno’s long, harsh winters in comfort.

Tōno Furusato Village

Tōno Furusato Mura is an extensive space that recreates the unspoiled landscape of old Tōno. The village contains relocated farmhouses, a nature museum, a dyeing workshop, a charcoal burner’s hut, a water wheel and rice and vegetable fields. The spacious visitor centre at the entrance to the village contains a restaurant, gift shop and library. Around twenty Maburitto take turns staying in the magariya and tending the surrounding fields.

Tōno Furusato Village, 5-89-1Kami-Tsukimoushi, Tsukimoushi-chō, Tōno, Iwate Prefecture

☎0198・64・2300

http://www.tono-furusato.jp/en/