Nara’s Kasuga Taisha, or Kasuga Grand Shrine, and its shrine precinct the Kasuga Primeval Forest were registered in 1998 as part of the eight-property Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara UNESCO World Heritage listing. Kasuga Grand Shrine rose to prominence in the late Nara Period (710 – 795) together with the growing prosperity of the powerful Fujiwara Clan, and evolved from being the family shrine of this influential clan to becoming a significant focus for the religious veneration of successive generations of emperors and nobility. The Kasuga Faith spread to the common people during the medieval era and branch shrines sprang up all over the country. Today there are as many as 3,000 Kasuga branch shrines in Japan.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photos : 谷口哲 Akira Taniguchi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Japan World Heritage / Heian Period / World Heritage Sites / Kasuga Grand Shrine / Nara Prefecture

Kasuga Shrine Rises to Prominence along with the Fujiwara Clan

Kasuga Grand Shrine is thought to have been established by the Fujiwara clan as a family shrine in 768 at the base of Mikasayama, the sacred hill behind the shrine where the gods are believed to have descended to Earth. However, Mikasayama’s history as a place of worship may significantly predate the establishment of Kasuga Shrine. recent investigations having revealed the remains of earthen walls topped with roofing tiles, as well as religious relics that suggest that this site was already being used for religious purposes long before Kasuga Shrine was built on the site.

There are four deities enshrined at Kasuga Shrine. The principal deity is Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto, who arrived at Mikasayama from Kashima Shrine in modern-day Ibaraki Prefecture, riding a white stag. Here in Nara, deer are believed to be the sacred messengers of the gods. Another deity, Futsunushi-no-Mikoto, came from Katori Shrine in modern-day Chiba Prefecture, while Amenokoyane-no-Mikoto and his consort, the goddess Himegami, were brought here from Hiraoka Shine, which is located at the western base of Mount Ikoma, between Nara and Ōsaka. As a female deity, Himegami later came to be worshipped by the followers of Amaterasu Ōkami, the sun goddess.

By the Heian Period (794 – 1185), the capital had moved from Nara to Kyōto and the Fujiwara clan, having intermarried with the imperial family, had grown in political strength and had become the de facto rulers of the country. Kasuga Shrine shared in the prosperity of the clan. The shrine precinct was greatly expanded, new main shrine buildings were constructed and auxiliary shrines established, resulting in a layout that remains much the same today. The number of priests and other clergy also increased greatly and Kasuga Shrine grew from being the family shrine of the Fujiwara clan to becoming the most important centre of worship for the entire Yamato Province (modern-day Nara Prefecture).

Such was Kasuga Shrine’s status that even emperors, themselves considered living gods, visited Kasuga Shrine regularly and the annual Kasuga Festival was attended by an imperial envoy each year. In 850 the enshrined deities Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto and Futsunushi-no-Mikoto were given the highest-level status in the shinkai system ranking the importance of deities; higher even than the imperial family. In 940 Amenokoyane-no-Mikoto joined his fellow Kasuga deities in this top ranking.

Kasuga Shrine itself was raised to the status of Myōjin Taisha, the highest rank of shrine listed in the Engi-Shiki, a book codifying Japanese laws and customs, compiled in 927. According to the shrine ranking in the Engi-shiki, enshrined deities of shrines of ancient and honorable origin, and renowned for their miracle-working powers, were given the title of Myōjin. The gods of Kasuga Shrine, once local deities, were by now called on to work for the wellbeing of not just Yamato Province, but of the entire nation.

The Changing Fortunes of Kasuga Shrine

Kōfukuji Temple, a Buddhist temple located nearby, was also a guardian temple of the Fujiwara family and, as such, was closely linked to Kasuga Shrine. As Buddhism became increasingly fused with the pre-existing local Shintō religious beliefs, Kasuga-Taisha Shrine and Kōfuku-ji Temple came to be regarded as a united body known as “Kasugasha-Kōfukuji”. At the same time, the four Kasuga deities came to be worshipped as the incarnation of Bodhisattvas. Kasuga Shrine’s Takemikazuchi-no-Mikoto came to be worshipped as Buddhism’s Fukūkensaku Kannon, and later as the Bodhisattva Shaka Nyorai. Futsunushi-no-Mikoto was worshipped as the Bodhisattva Yakushi Nyorai, and Amenokoyane-no-Mikoto as Jizō Bosatsu. Himegami, the female deity, was worshipped as the eleven-faced Kannon.

Kōfukuji’s controlling power became stronger over time as Buddhism absorbed local religious traditions and the line between Buddhism and Shintoism disappeared. In fact, although Wakamiya Shrine, an auxiliary shrine near Kasuga Shrine, is thought to have been established by Fujiwara no Tadamichi, chief advisor to the emperor, some believe that the Buddhist monk-soldiers of Kōfukuji were behind the 1135 establishment of this Shintō shrine. Indeed, the annual Wakamiya Onmatsuri festival, which began the year after the shrine was established, was run under the auspices of Kōfukuji Temple until the 1600s. Regardless, the Kasuga Faith thrived and continued to spread, with subsidiary shrines established all over the country on land owned by the Fujiwara clan or by the Kasugasha-Kōfukuji temple-shrine complex. Both Shintō rituals and Buddhist masses were conducted in these shrines.

The years 1336 to 1392 saw rival imperial courts set up in rival capitals; the Northern Court established by self-styled shōgun Ashikaga Takauji in Kyōto and the Southern Court established by Emperor Go-Daigo in Nara. Interestingly, when Kasuga Shrine was entirely destroyed by accidental fire in 1382, it was rebuilt with aid from third Ashikaga Shōgun, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who was based not in Nara, but in Kyōto. However, during the time of civil war and social upheaval that ensued for a century and a half from the late 1400s, Kasuga Shrine lost the patronage of both the imperial nobility and the warrior samurai clans and fell into decay and obscurity. Nevertheless, the Kasuga faith and its rituals had by this time been established throughout the country, and had spread from the samurai and nobility to the common people.

Kasuga Shrine was finally restored to its former glory during the rule of the Tokugawa clan (1603 – 1868), when the present-day main shrine buildings and many of the other structures at the site were rebuilt.

Up until the Meiji Restoration of 1868, a revolution that swept the Tokugawa clan from power and replaced eventually by a constitutional government with the emperor as the nominal head of state, nationalistic sentiment among Japan’s new leaders saw Buddhism denounced as a foreign import. Accordingly, laws were passed requiring that the two religions be separated. Known as Shinbutsu-bunri, this forced separation was incidentally a way to reduce the power and wealth of the Buddhist sects, many of which had even had their own armies in the past, and still controlled vast areas of land, including many Shintō shrines.

The forced separation of Buddhism and Shintōism saw the end of Kōfukuji Temple’s control of Kasuga Shrine, and all signs of Buddhism were swept from the Shrine precinct. In 1871, three years after the establishment of the Meiji Government, Kasuga Shrine was designated a Kanpei-sha (Imperial Shrine) of the first rank. In 1946, the shrine, which had previously been known as Kasuga Jingū (Shrine), was renamed Kasuga Taisha (Grand Shrine), bringing us up to the present day.

property. The main sanctuary and its four halls dedicated to each of the four

Kasuga deities are accessed through this gate. The garden in front of the

Chūmon Gate is known as the Ringo no Niwa (Apple Garden), and is where the

Kasuga Festival takes place.

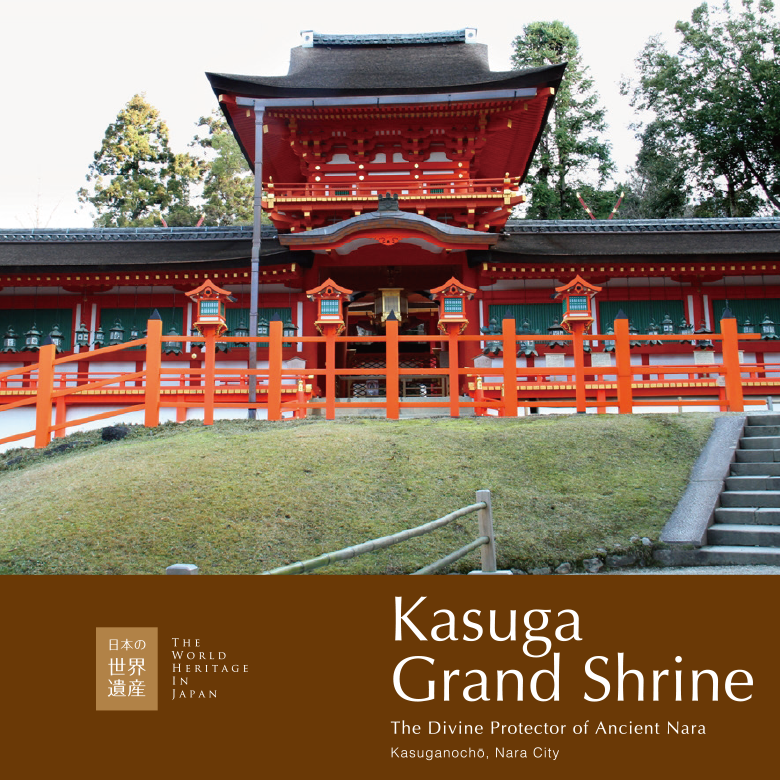

Mysterious World Nestled within the Eternal Forest

Kasuga Shrine and its surrounding forest, a vast sanctuary in the eastern part of Nara City that forms part of Nara Park, covers over 93 hectares. The shrine is accessed via a long path through the woods, which culminates at the four small shrine buildings housing the Kasuga deities. Standing side by side arranged east to west, each of the buildings has an elegantly upswept gabled roof known as a kirizuma roof (https://manabi-japan.jp/en/art-design/20200401_20235/) clad in cypress bark shingles, with the entrances at the front gable end of each tiny hall, a style of shrine architecture known as Kasuga-zukuri. A small veranda-like platform and steep sets at front of each hall is protected by a canopy roof extending from the gable end. Although the current shrine buildings date back only to 1863, they retain the architecture of the original shrine buildings and are designated as national treasures.

Kasuga Shrine is renowned for its stone lanterns and hanging bronze lanterns, which number around three thousand. It’s even rumoured that anyone who succeeds in counting the hundreds of moss-covered stone lanterns lining both sides of the approach path to the shrine will be showered in good fortune! Most of the lanterns have been donated by common people, but some of the oldest date back to the Heian Period (794 – 1185), before the Kasuga faith had spread from the nobility to commoners.

The oldest hanging lanterns decorating the halls and cloisters of the shrine date back over five centuries and feature various fretwork designs and family crests. The lanterns are lit twice a year, with the Setsubun Mantōro lighting of the lanterns taking place on the night of the Setsubun festival (February 3rd) and Chūgen Mantōro on August 14th and 15th. This is a truly mystical sight to behold, as the lanterns illuminate the shrine grounds and the walking paths through the woods.

without interruption since 1888. The sight of thousands of glowing lanterns is

an unforgettable experience.

The annual Kasuga Taisha festival is held on March 13th. The Kasuga Festival, along with Kyōto City’s Kamo Festival (perhaps better-known as the Aoi Matsuri) and the Iwashimizu Festival in Yawata City just south of Kyōto, is one of the three big Sanchokusai festivals, held by imperial order. The festival re-enacts scenes from the Heian Period (the golden age of the Fujiwara clan), with participants in period costume and dances such as Azuma-asobi and Yamato-matoi performed as offerings to the gods.

In mid-December, the city of Nara is abuzz with the sights and sounds of the Kasuga Wakamiya On-matsuri, a festival designated as a National Important Intangible Folk Cultural Property. The event spans four days, with traditional dance performances, and a torchlit procession in the wee small hours of December 17th, during which the divine spirits of Wakamiya Shrine are conveyed to Otabisho, a temporary sanctuary near the first torii gate. A highlight of the Kasuga Wakamiya On-matsuri is the ‘jidai gyōretsu’ procession with five hundred participants, many on horseback, dressed as priests, samurai warriors or feudal lords, as well as in costumes from local traditional arts. The costumes represent the successive eras from the Heian Period (9th to 12th century) through to the late Edo Period (19th century).

dates back to 1137, and was donated by Fujiwara no Tadamichi, an influential

member of the politically powerful Fujiwara clan.

A Primeval Forest Brimming With Plant Life

The Mt Kasuga Primeval Forest, an area of forest-clad hills to the north and east of Kasuga Shrine, is included in the Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara UNESCO World Heritage listing. The forest forms the shrine precinct and includes Mikasa-yama, the sacred hill at the base of which the shrine was established. The forest has been protected for almost 1,200 years, with hunting and tree-felling having been prohibited since 841. Although directly adjacent to the city of Nara, Mt Kasuga, which was designated a special natural monument in 1955, has retained it primeval qualities and its rich variety of tree species and other plant life, making the forest and its ecosystem of great interest scientifically.

Despite being located in the northern warm temperate climatic zone, Mt Kasuga Primeval Forest has a distinctly sub-tropical atmosphere, due to an extraordinarily large number of plant species belonging to the southern warm temperate zone. Stands of tall, warm-climate trees species such as the Asian bayberry (Nageia nagi, a broadleaf conifer) grow wild here, in defiance of the region’s cold winters. In addition to a complex variety and distribution of temperate trees, warm-climate vines and ferns grow profusely in the dense interior of the forest. In fact, there are believed to be over a thousand different plant species growing in Mt Kasuga forest, and a 2002 survey counted over 1,400 giant old trees here.

In line with the sacred and protected status of Mt Kasuga Primeval Forest, the public is not permitted . Although setting foot on the sacred forest floor itself is strictly prohibited, Mt Kasuga Primeval Forest is part of the 660-hectare, heavily forested Nara Park. The Nara Okuyama Driveway scenic route, which passes through part of the virgin forest, allows glimpses into the secluded depths of the forest, and a number of walking routes through the woods adjacent to the sacred forest also enable glimpses of the giant trees within. From the top of nearby Wakakusa-yama, a grassy hill also within Nara Park and accessed by several walking paths, one can look down over the sacred forest and its myriad shades of green.

As a natural area that, together with the main shrine, forms a unified cultural landscape with an important role in the conservation of Nara’s landscape, Mt Kasuga Primeval Forest was designated by UNESCO as a Cultural Heritage rather than a Natural Heritage site. The sacred forest, protected in its untouched state, evokes a sense of divinity and awe. Here one can begin to understand how nature inspired and infused Japan’s traditional religious beliefs.

of Kofukuji Temple recited Buddhist sutras here. The wall visible beyond the

Orō is part of the East Cloister, with the dense growth of the Kasuga Primeval

Forest visible behind it.