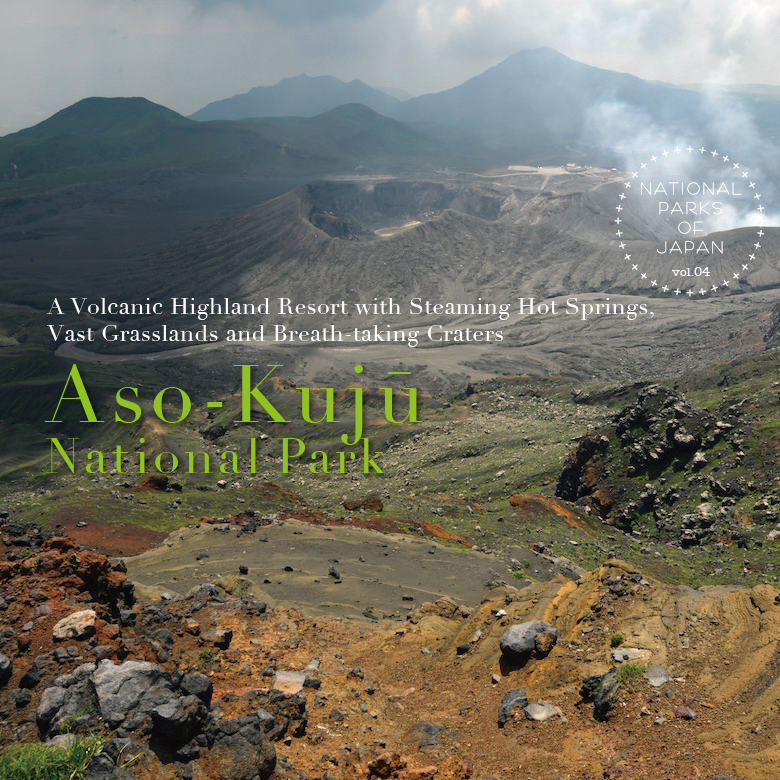

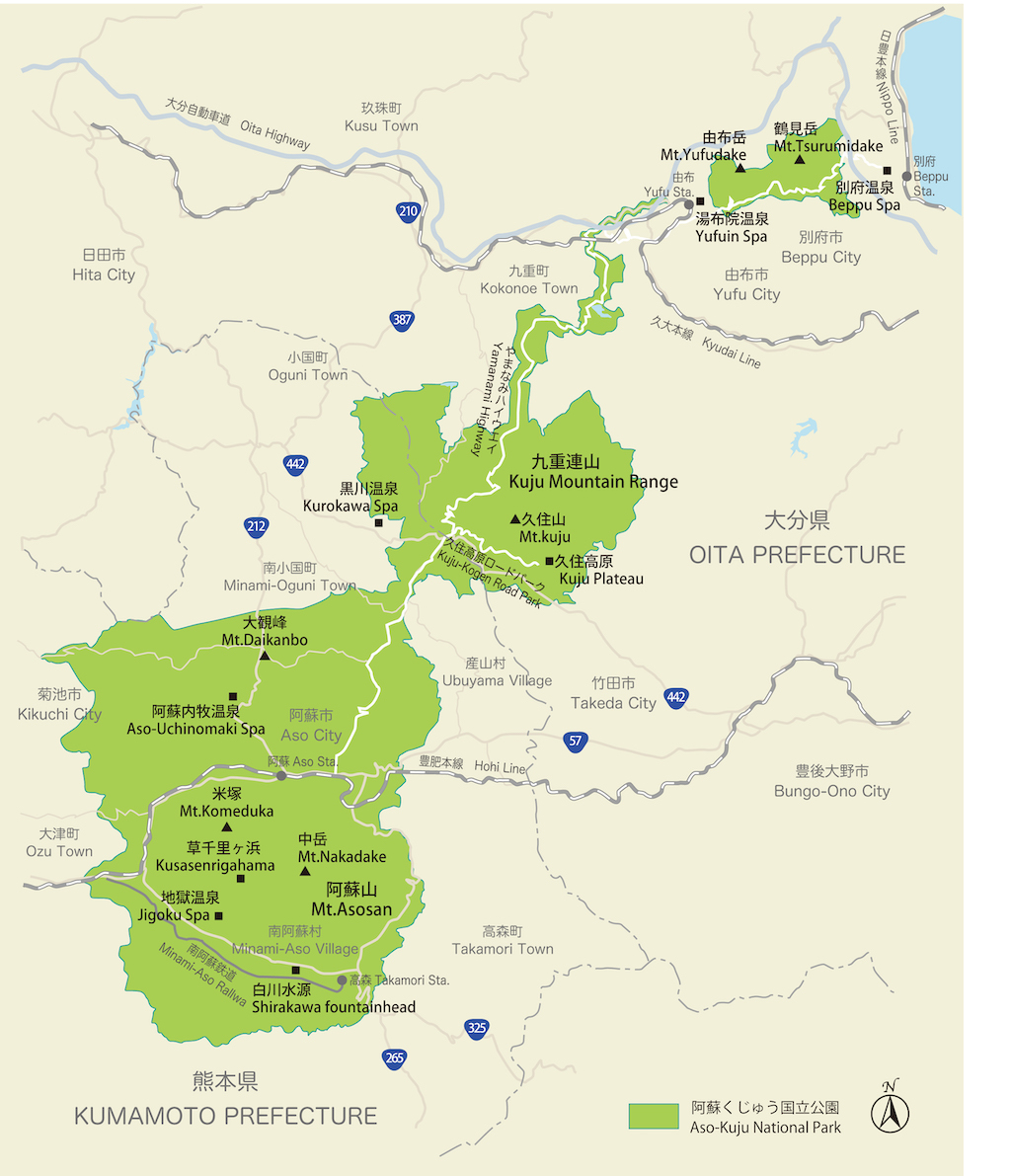

Created in 1934, the volcanic Aso-Kujū National Park was one of Japan’s first national parks. The park is one of Kyūshū’s leading tourist destinations and covers an area of 729 square kilometres, extending into both Kumamoto and Ōita Prefectures. Blessed with abundant natural hot springs, Aso-Kujū National Park comprises three distinct areas. The massive Mt Aso sits right in the centre of Kyūshū, with the Kujū volcanic group to its north-east. Further east still, towering over the hot springs town of Beppu, are the iconic peaks of Yufudake and Tsurumidake.

Photos : 谷口哲 Akira Taniguchi / Text : Sasaki Takashi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Mt Aso / Caldera / Crater / Volcanoes / Beppu / Yamanami Highway / Kumamoto Prefecture / Onsens / Ōita Prefecture / Aso-Kujū National Park / Kyushu

Aso-Kujū National Park

Located in central Kyūshū, Aso-Kujū National Park comprises the Aso Caldera (one of the largest calderas in the world); as well as a volcanic group extending to the north of the caldera that includes the Kujū Mountains, and vast swathes of grassland surrounding the caldera and mountains. Aso-Kujū National Park was one of five national parks established on December 4, 1934. The others were Akan National Park, Nikkō National Park, Chūbu Sangaku National Park, and Daisetsuzan National Park. Originally known as Aso National Park, it was renamed in 1986.

The Majesty of Nature on Display in this Massive Volcano

At the heart of Aso-Kujū National Park sits the sprawling Mt Aso, an active and still-smoking volcanic cluster, and the reason why Kumamoto is known as the Land of Fire.

Mt Aso, a volcanic cluster that began forming several hundred thousand years ago, is the collective name for an area that includes one of the world’s largest calderas, the group of volcanic cones located within the caldera, and the outer wall that encircles it. The caldera was formed through a series of gigantic eruptions, as the magma and gases emptied out from under the ground and the earth collapsed into the huge empty chamber beneath. The central volcanic cones emerged after the formation of the caldera, giving us the “volcanoes within a volcano” that we see today. Deposits from the pyroclastic flow ejected during Mt Aso’s huge eruptions covered most of Kyūshū and reached as far as the neighbouring islands of Honshū and Shikoku.

The caldera, stretching 18 kilometres from east to west and 24 kilometres north to south, has a circumference of 128 kilometres. The “Five Peaks of Aso”, the volcanic cones in the centre of the caldera, are Takadake (1,592 m), the tallest, followed by Nakadake (1,506), Nekodake (1,433 m), Eboshidake (1,337 m), and Kishimadake (1,321 m). Nakadake can be identified by the huge gouge taken out of its western side, as well as by the smoke this volcano continuously belches out. Constant rumblings from its crater remind all of the power and wonder of nature.

The outer rim of the Aso caldera to the north of the central volcanic cones comprises a series of flat-topped ridges, rising to a height of around 900 metres. The opposite end of the rim to the south is a continuous wall of undulating peaks and valleys reaching 1,000 metres in elevation. Long ago, a route through this section connected the people of the caldera to the outside world. The inner walls of the caldera are precipitous, with many sheer cliffs. In contrast, the land on the outside of the caldera wall slopes more gently, and has long been used to graze livestock.

The central volcanic cones can be viewed from several spots along the caldera wall, including Daikanbō, a 939-metre-high point on the northern caldera wall. From here, the outline of the central cones is said to resemble the sleeping Buddha.

A Gigantic Water Basin Feeding into Kyūshū’s Major Rivers

Kyūshū’s major rivers all have their source in the Aso Mountains. Four of these rivers (the Shirakawa River which collects the waters of the basin floor; the Chikugogawa River from the northern caldera rim, and the Kikuchigawa and Midori Rivers from the western rim) flow west into the Ariake Sea. The waterways of the eastern rim join with the Ōnogawa River to flow northeast into Beppu Bay. Meanwhile, the streams and waterways from the southern rim form the Gokasegawa River flowing through Miyazaki Prefecture and into the Hyūga-nada Sea.

Onsen (hot springs), found in great abundance both inside and outside the Mt Aso caldera wall, are an important tourist attraction. Some of the baths are said to date as far back as 1,800 years ago, to the time of the Empress Jingū. Others retain the air of Japan’s old-fashioned “therapeutic baths”. Onsen of all different types can be found in the popular and picturesque hot spring villages, as well as in more isolated, quiet locations alongside remote mountain streams. With such a variety of hot springs to suit all tastes, there’s sure to be something here for everyone.

Landscaping on a Monumental Scale

Open grasslands stretching as far as the eye can see epitomise the Aso landscape. However, these grasslands did not occur naturally, but are the result of over a thousand years of management involving a cycle of haymaking, controlled burning, and pastoral grazing.

Haymaking takes place in autumn, when the towering grasses are cut and dried to be used as winter fodder. The following spring, controlled burning known as noyaki takes place. This burning stimulates the regrowth of pasture grasses and inhibits the regeneration of unwanted vegetation. Plumes of smoke rising up from the grasslands are a common sight in spring, while horses and cattle graze the land from spring through autumn. Their weight as they roam the pasture helps keep the height of the grass down, resulting in open meadows such as Kusasenri, on the northern slopes of Mt Eboshi-dake.

People have lived within the walls of the caldera since ancient times. The present population numbers around 50,000, with many engaged in farming and forestry activities, including the breeding of the local akaushi cattle and the production of Oguni-sugi cedar. More recently, tourism has grown to become an important part of the local economy.

A volatile environment fosters a healthy respect for nature. Aso Shrine, dedicated to the god of fire of the Aso volcanoes, has long held an important place in the lives of the people of the caldera. Believed to have been established over 2,000 years ago, Aso Shrine was once a major imperial shrine, and has subsidiary shrines all over Kyūshū. Centuries-old sacred music and dance known as kagura are still performed regularly. Visitors have the chance to see the celebrated Iwato Kagura performed at Nagano Aso Shrine in Minamiaso Village each year in May and October.

A Rich and Varied Volcanic Plateau, Abundant Water Resources and Beautiful Wetlands

In contrast to the sprawling basin-shaped caldera of Mt Aso, the soaring mountains of Kujū comprise over twenty bell-shaped lava dome peaks.

The majestic Kujū Mountain Range, located in western Ōita Prefecture and known as the Roof of Kyūshū, stretches 22 kilometres from east to west and 24 kilometres from north to south. Here we find Kyūshū island’s highest peak, also called Nakadake (1,791 m), alongside its neighbours Mt Kuzumi (1,787 m) and Mt Taisen (1,786 m).

Many of the mountains here are lava domes, formed when lava forced up from beneath the earth solidified. The remains of explosion craters can be seen in the form of ponds such as Karaike and Miike on Mt Kuzumi, as well as Oike pond on Mt Taisen. The area’s geothermal activity has been harnessed at Hatchōbara, Japan’s largest geothermal power station.

The landscape of the foothills north and south of the mountains is rustic and idyllic. Highlands such as Kuzumi Kōgen and Handa Kōgen were formed from pyroclastic flows from the Aso and Kujū volcanoes. The extensive grasslands here are managed through livestock grazing and controlled burning, just as on Mt Aso.

A number of rivers have their source in this volcanic zone, later merging with the rivers flowing from Aso. Originating in the northern part of the range, the Kusugawa River joins the mighty Chikugo River near the town of Hita. Meanwhile, rivers such as the Kanbagawa River from the south of the mountain group merge with the Ōno River in the Taketa area.

Keeping Japan’s Most Abundantly Flowing Onsen Brimming with Hot Water

Aso-Kujū National Park is home to unique and important wetlands. The marshes of Bōgatsuru-shitsugen and Tadewara-shitsugen lie nestled in a basin, surrounded by volcanoes. With a combined area of 91 hectares, these are the largest intermediate moors of mixed sphagnum bogs found in any of Japan’s mountainous areas, and are protected under the Ramsar Convention.

At the northernmost end of the national park are two more of Kyūshū’s iconic mountains, Yufudake (1,583 m) and Tsurumidake (1,375 m), said to be the source of Beppu’s plentiful thermal springs. Yufudake, dubbed the Bungo Fuji because of its graceful conical form, has been the inspiration for many a poem over the centuries. At the base of the mountain lies the thriving village of Yufuin Onsen, a picturesque spa resort attracting many artists and writers, and particularly popular with summer visitors.

Mt Tsurumi has erupted frequently in the past and volcanic gases continue to be detected even now. Lake Shidakako, a popular tourist spot at the south-eastern base of the mountain, was formed by a volcanic explosion around the time of the Heian Period, some 1,200 years ago. A ropeway (aerial cable car) runs from the base of Mt Tsurumi, all the way to the top. From the summit, visitors can look out across Beppu, the hot spring town that boasts the greatest number of hot springs and the highest flow rate of all Japan.

Aso-Kujū National Park has an excellent road network, making it easy to get right into the heart of the park. Stunning views of this dynamic landscape can be enjoyed from the Yamanami Highway connecting Yufuin with Aso, or from the Aso Milk Road, a scenic route running along the top of the northern section of the caldera rim.

Stars of the Highlands – Azaleas in Early Summer and Silvergrass in Autumn

While the maintenance of the grassy highlands of Aso and Kujū prevents the land from reverting to forest, precious virgin forests do nevertheless remain in areas such as Kikuchi Gorge on Aso’s western caldera rim and Kitamuki Valley on the southern rim, as well as around the mountains of Nekodake in Aso, and Kurodake (1,587 m.) in Kujū.

Iconic Kyūshū azaleas (Rhododendron kiusianum) grow in large colonies high on the mountains across the national park, blooming in early summer. In the highlands of Aso there are many plant species that are also found on the Asian continent, such as violets (Viola orientalis), purple asters (Aster maackii) and clustered bellflowers (Campanula glomerata). Sedge grass (Carex chrysolepis) grows en-masse around Nakadake, oblivious to the volcanic smoke.

At Mt. Taisen in Kujū, lingonberries (Vaccinium vitis-idaea) and fringed galax (Schizocodon soldanelloides) grow around the summit. Silvergrass (Miscanthus sinensis) and dwarf bamboo (Pleioblastus chino) predominate in the areas harvested for hay, while the grazing land is mainly Zoysia grass and bracken. The star of the highlands, the towering silvergrass is particularly beautiful in autumn.

Foxes are the most numerous wild animals in Aso, followed by monkeys, wild boar and tanuki, a nocturnal member of the dog family native to Japan. Around eighty species of birds have been recorded in the area, including the golden eagle. As for insect life, the endangered butterfly, Shijimiaeoides divinus is often sighted, while as many as thirty species of scarab beetle thrive on horse and cattle dung.

Birdlife is even more prolific over on the Kujū plateau, where a hundred and twenty different bird species have been recorded. Songbirds such as the blue-and-white flycatcher, the narcissus flycatcher and the Japanese grey thrush are especially popular with bird lovers.