It has no form and can’t be seen or touched, but its scent holds a mysterious power: the ability to calm the mind, sharpen the senses and raise the spirits. In Japan, the art of appreciating fragrance has been codified into a tradition known as Kōdō, ‘The Way of Fragrance’.

Text : Sasaki Takashi / Photos : 平島 格 Kaku Hirashima / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Incense / Kōdō / Cultural Studies Series / Fragrance

The enjoyment of fragrance refined into an art form

Natural fragrant woods have long been used in India to mask unpleasant smells caused by the intense heat. These fragrances spread from India to the rest of the world. In the West they became perfumed oils and colognes, while in the East they were made into balls of incense (nerikō) or incense powder (makkō).

“Fragrance is enjoyed in various ways all over the world but it’s only here in Japan that this appreciation has been refined and raised to the level of an art”, says Yoshihiro Inasaka, president of Koju, an incense company established over 400 years ago.

Setting all thoughts aside to listen to the fragrance

One aspect of kōdō is the incense ceremony, which, like sadō (the tea ceremony), has its own set procedures. Two important elements of the incense ceremony are monkō (‘listening’ to the incense) and kumikō, an incense matching game.

Monkō involves calming the mind and ‘listening’ to the fragrance. Whether you ‘listen’ to it or ‘smell’ it, the idea is to clear the mind in order to discern the depth and subtlety of each incense.

According to Inasaka-san, our sense of smell is the least used of our five senses, so it takes a considerable degree of focused attention to tell the difference between similar fragrances.

There are no wasted movements in the tranquil space of kōza (the incense ceremony itself). The gentle manners and calm movements of kōza are believed to be one way of focusing the consciousness on the fragrance of the incense.

Kumikō – a guessing game

After listening to the different incenses, guests try their hands at kumikō, a game that draws on allusions to classical Japanese literature. There are several hundred varieties of kumikō, based on themes from classical poetry, literature or historical stories. The most popular theme of all is Genji-kō, based on the classical 11th century novel, The Tale of Genji.

The kōmoto (host of the ceremony) and the record keeper take the place of honor, both sitting on a scarlet mat at the head of the group while the participants make up the other sides of a rectangle. Five packets each of five different aromatic woods (25 samples in total) are prepared. From this, five packets are randomly chosen for smelling. The censers are passed from one participant to the next, beginning with the kōmoto. Participants inhale the fragrance, ‘listening’ to see which (if any) of the five samples are the same, and which are different.

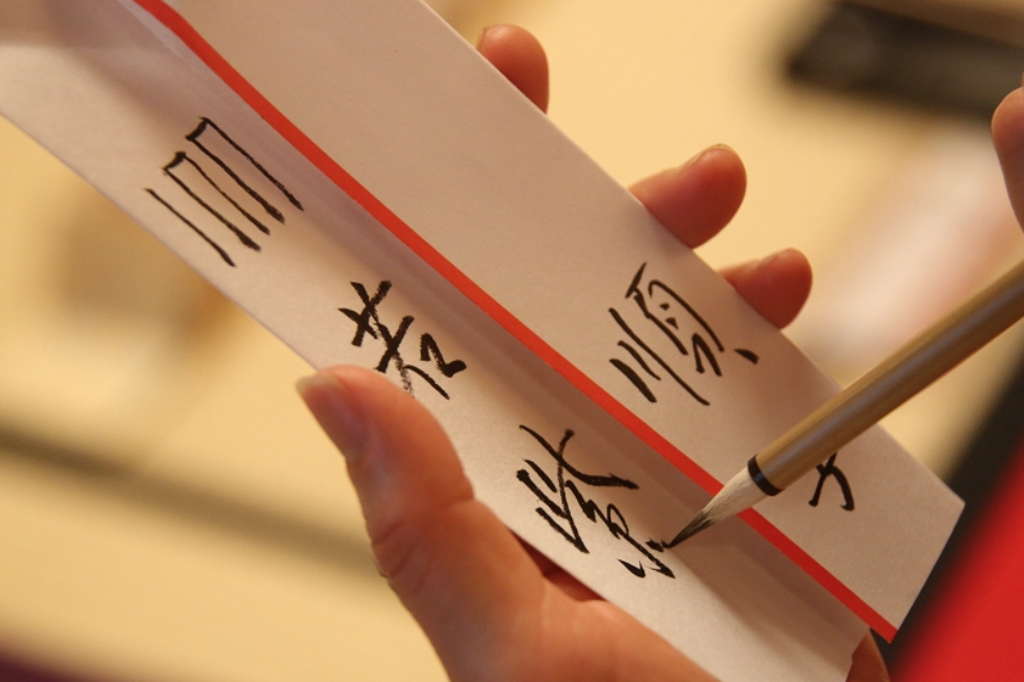

There are 52 possible match combinations in Genji-kō, each named after a chapter from Murasaki Shikibu’s classic novel. The Tale of Genji actually consists of 54 chapters but the first and last are omitted for this game. After listening to each of the scents, participants draw five vertical lines on a piece of paper, one for each of the samples. They then identify which of the samples they believe are the same as each other by connecting two or more of the vertical lines with horizontal lines at the top to produce a diagram. Beneath this they write the name of the Genji chapter that their combination corresponds to.

Samurai Warriors and the World of Fragrance

According one of Japan’s oldest historical records, the Nihon-shoki (Chronicles of Japan), incense first arrived in Japan in 595, almost one and a half millennia ago. It is generally accepted that incense was first used for religious purposes, based on evidence that pieces of precious fragrant wood were included among the many scriptures and religious objects that Buddhist monks visiting Japan or returning from abroad brought with them. And in fact, the tradition of burning incense at funerals and Buddhist memorial services has continued unchanged for over 1,400 years.

Sometime after the introduction of incense to Japan, sora-takimono (incense) was used by Heian period (794-1185) aristocracy to fragrance their hair, clothes and rooms. Members of the Heian court entertained themselves with takimono-awase, competing with one another to create the best incense blends. Incense features frequently in Murasaki Shikibu’s classic novel, The Tale of Genji, which dates from this period.

By the 13th century, appreciating the scents of the incense woods themselves, rather than incense blends, had become a popular form of entertainment. Before long, the kumikō guessing games described on the previous page were developed.

Kōdō became established as an art form in the 15th century during the latter part of the Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573) when Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa appointed two experts to formalise this popular entertainment. Sanjōnishi Sanetaka created the Oie School of kōdō, while Shino Sōshin created the Shino School, both of which have continued in an unbroken tradition to this day.

Once a rarefied form of entertainment for the aristocracy, kōdō spread with the establishment of the samurai military government at the end of the Heian Period and became one of the samurai arts. It may surprise many to learn that, starting with Oda Nobunaga, the samurai of the Sengoku (Warring States) period practiced not only the tea ceremony, but also the ‘Way of Incense’.

Yoshihiro Inasaka, head of the Koju incense company, believes that the reason kōdō was adopted by the samurai class was because it helps sharpen all five senses. Inasaka-san explains that the practice of stilling the mind and focusing ones consciousness in order to discern subtle fragrances stimulates and hones all the senses. This is something that the samurai, who put their lives on the line during battle, would have instinctively understood.

Rikkoku-gomi: classifying fragrant woods and their scents.

None of the precious fragrant woods used in kōdō come from Japan originally; they are all imported and are all extremely rare. The scent of jinkō (agarwood), for example, results naturally when the resinous trunks of fallen Aquilaria trees lie under the ground for hundreds of years. The fragrance gradually results from a reaction to microorganisms that attempt to break down the wood. At some point in the distant past, this phenomenon was discovered and the logs sought out and unearthed. Eventually some of this precious wood made its way to Japan, the final stop on the Silk Road.

Each of the six types of wood is named for its country of origin, and is further classified by its ‘flavour’. Rikkoku-gomi, the term used to classify fragrant woods, literally means ‘six countries, five flavours’. The names of the incense woods are kyara (Vietnam), rakoku (Thailand), manban (origin unknown), manaka (Malaysia), soraya (India) and sumotara. The five ‘flavours’ are sweet, sour, spicy, bitter and salty.

While it is often said that a gram of precious fragrant wood costs several times more than a gram of gold, the value of kyara, the very finest quality agarwood, is in fact several dozen times the price of gold.

This precious incense wood is indeed valuable, but in the world of kōdō, its fragrance is not something that people spend hours wastefully indulging in and it would never be used to scent an entire room. Participants in the incense ceremony have only three breaths to ‘listen’ to the incense. That’s about ten seconds to hear the voice of this ancient scented wood and interpret what it is saying.

Kōdō is a peculiarly Japanese discipline derived from the combination of an incense culture that was brought to Japan over a thousand years ago with a uniquely Japanese spirit and aesthetic.

Yoshihiro Inasaka

Yoshihiro Inasaka heads the Koju Ginza branch, established in the Tenshō Era (1573-1592), around 430 years ago. He gives presentations and lectures to inform the public about Japan’s incense traditions and is referred to the ‘incense evangelist’ by the media. He has authored a number of works, including Kaori to Nihonjin (Incense and the Japanese).

Getting started with kōdō.

Koju-an in Ginza, Tokyo, provides incense experiences for visitors from abroad. Phone 03-3541-3441 for more information.

In addition, Oie-style kōdō classes (in Japanese) are held every month on a regular basis. For the regular classes, if wearing Western-style clothing (kimono is not necessary), please ensure that you bring a pair of clean white socks that cover the ankle, to put on when you enter the room. At the time of writing (October 2018) the joining fee is 3,000 yen and membership fees start at 16,500 yen for three classes (one per month).

For those who want to find out if kōdō is for them before signing up for regular classes, trial lessons are available at 5,000 yen (no joining fee).

“Learning kōdō isn’t like learning calligraphy,” laughs instructor, Gyōsetsu Maruyama. “You don’t have to prepare, and there isn’t any homework!” All it takes, according to Maruyama-sensei, is the desire to enjoy the fragrance.

Ginza Kōjū – ‘Koju-an’

3F Kodo Building, Ginza 4-9-1, Tokyo.

03-3574-6135 (in Japanese)