Flowering plants are intricately woven into the tales and legends of Japan, and feature prominently in Japanese art and poetry. Brimming with intelligence and ingenuity, the flowering plants all around us herald the coming of the seasons. Whether you live in Japan or are here as a visitor, take a moment to look about and see what the flowers have to tell you.

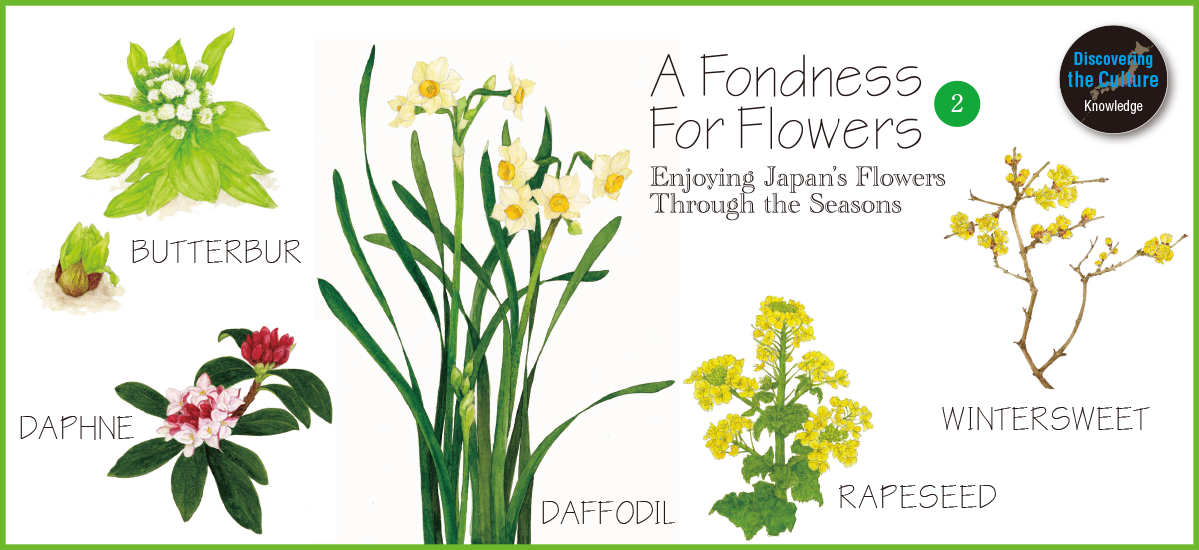

Illustration : Aso Yuriko / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Man’yōshū / Ume / Japanese Plum

Suisen (水仙) – Daffodil

Plant Family: Amaryllidaceae.

Botanical name: Narcissus tazetta var. chinensis.

Common Japanese names: suisen; setchūka.

Common English names: Narcissus; Daffodil.

Place of origin: Mediterranean coast.

Prefectural plant: Fukui Prefecture.

Language of Flowers: conceit; narcissism.

A topic of conversation in spring – but not just for its beautiful flowers!

Commonly known in Japanese as suisen, daffodils are also known as setchūka, meaning flowers in the snow. The daffodil is one of the first flowers to announce the coming of spring, sitting alongside plum blossom, wintersweet and camellia as one of the “Four Friends of the Snow” (Setchū no Shiyū), and alongside plum blossom and daphne as one of the “San no Kimi”, three auspicious flowers depicted in paintings that celebrate the coming of spring.

The botanical name Narcissus derives from the ancient Greek tale of a beautiful but conceited youth of the same name. In one version of the tale, Narcissus falls in love with his own reflection in the surface of a pond. Transfixed by the beauty of his own image and unable to leave, he remains at the edge of the pond where he dies and is eventually transformed into a clump of daffodils. And this, so the story goes, is why daffodils can be found growing next to water, their trumpet-shaped blooms gazing down at their reflections. The Japanese daffodil (Narcissus tazetta var. chinensis), one of many different species of Narcissus, has a yellow trumpet-shaped corona above a whorl of white petals that form the perianth. Despite its name, the Japanese daffodil is not native to Japan, but originated in coastal regions of the Mediterranean and was introduced to Japan via China many centuries ago. It naturalised here and has formed extensive colonies in many parts of the country.

The Man’yō-shū (Japan’s oldest anthology of poetry that dates back over 1300 years to the Nara period) is full of poems about flowers, but, having been compiled before the daffodil was introduced to these shores sometime between the late Heian Period (794 – 1185) and the early Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573), it contains no reference to the daffodil.

As soon as its flowers start to open in early spring, the cheerful flowers of the daffodil becomes a topic of conversation. However, by April and May the daffodil is once again back in the news for entirely the wrong reasons. It turns out that the daffodil’s spear-shaped leaves look just like the leaves of the garlic chive, and these are sometimes mistakenly harvested together, leading to some nasty cases of poisoning. In common with other Amaryllidaceae species such as snowdrops and spider lilies, daffodils contain the highly toxic alkaloid, lycorine. Ingesting even small quantities of this poison causes nausea and vomiting. To be on the safe side, daffodils should always be grown in a separate part of the garden from edible plants such as garlic chives

Fuki (蕗) – Japanese Butterbur

Plant Family: Asteraceae.

Botanical name: Petasites japonicus.

Common Japanese names: Fuki; Fukinotō; Kantō.

Common English names: Butterbur; Japanese butterbur; Giant butterbur; Sweet coltsfoot.

Place of origin: East Asia, including Japan.

Prefectural plant: Akita Prefecture.

The Tale of the Butterbur Flower and its Grateful Student

Butterbur is thought to be one of Japan’s oldest vegetables. Its botanical name, Petasites japonicus, derives from its broad round leaves. “Petasites” means “wide-brimmed hat”, while “japonicus” pertains to Japan.

In early spring, the rhizomes push the flowering buds, fukinotō, up through the snow to announce the coming of spring – a phenomenon that has given rise to the tale of the butterbur flower and its grateful student.

———Once upon a time, long, long ago, a certain someone, transparent and entirely without colour, gazed wistfully at all the beautiful colours of the flowers and wished that it, too, had a beautiful colour of its own. It went to each of the brightly-coloured flowers in turn, asking them to show it how to make itself as colourful as them. Whether it was that they didn’t want to share their secret, didn’t know how to teach, or perhaps just simply couldn’t be bothered, none of the flowers would help.

The plain white butterbur flower watched as each of the bright flowers refused to help. Moved by this certain someone’s sadness, the humble butterbur offered to help. “If you don’t mind being just an ordinary white colour like me, I’ll try to show you how”, it said.

The simple butterbur gathered up all its ingenuity to teach its new student how to make itself white and, after much trial and error, they finally succeeded. The once transparent and colourless student was now a lovely white.

Not content to be just an ordinary white though, the butterbur’s student kept trying so hard to be the best white that ever was. It worked and worked at it until eventually, it became the most beautiful, most dazzling white that anyone had ever seen.———

Have you worked out who the butterbur’s student was?

———Blanketing the land and plants throughout the winter, it yeilds to the butterbur out of gratitude to its former teacher, melting and disappearing as soon as the butterbur buds begin to push up from the earth. ———

Yes, the butterbur’s student was the snow!

Rōbai (臘梅) – Wintersweet

Plant Family: Calycanthaceae.

Botanical name: Chimonanthus praecox.

Common Japanese names: rōbai; kara-ume.

Common English names: Wintersweet; Japanese allspice.

Place of origin: China.

Language of Flowers: guidance; foresight; kindness.

Wintersweet by any Other Name

Wintersweet, a flowering shrub that blooms in the depths of winter, is one of the “Four Friends of the Snow” (Setchū no Shiyū), four plants that flower in the snow that includes plum, camellia and daffodil. Its Japanese name, rōbai, is written with the characters 臘梅. The first character means “twelfth month” and the second means “plum”. Alternatively, you might sometimes see it written as 蠟梅, which mean “wax” and “plum”. Both are pronounced rōbai though.

Rōgetsu, the twelfth month of the old lunisolar calendar, corresponds to February, which is when wintersweet blooms, so the name rōbai (twelfth month plum) makes sense. Equally plausible though, because the semi-transparent yellow flowers that appear on the bare branches in the heart of winter look just as if they were made from wax, “wax plum” makes sense as well. Regardless of how you write it, wintersweet by any other name would surely smell as sweet!

There at least three different theories that seek to explain why the character 梅, or plum, is used in the name. One holds that it’s because the blossoms resemble plum blossoms; another argues that it’s because the branches resemble those of the plum tree, while a third theory is that it’s because the fragrance of wintersweet resembles that of the plum blossom. Despite its Japanese name though, there is no close botanical relationship between wintersweet and the plum. The English name, wintersweet, derives from the distinctively sweet fragrance of the flowers and the fact, obviously, that it flowers in winter.

In the language of flowers, wintersweet symbolises kindness because of the gentle, soft appearance of its flowers, and guidance and foresight as it is one of the first plants to flower, when the country is still in the grip of winter’s cold.

Jinchōge (沈丁花) – Winter Daphne

Plant Family: Thymelaeaceae.

Botanical name: Daphne odora.

Common Japanese names: Jinchōge; senrikō; rinchōge.

Common English names: Daphne; winter daphne.

Place of origin: China.

Language of Flowers: prosperity; sweet memories; perpetual youth and longevity.

The Fragrance that Travels a Thousand Miles

In Greek mythology, Daphne is the name of a nymph who, in an attempt to escape Apollo’s amorous advances, was transformed into a tree. This tree was known as daphne to the ancient Greeks, but we know it in English as bay laurel, the shrub that gives us fragrant bay leaves for our stews. Apollo is depicted wearing a crown of laurel, and laurel wreaths were awarded to champion athletes, including at the ancient Olympic Games. The leaves of the bay laurel and what we now know as daphne do bear a certain resemblance, so perhaps this is why the name daphne transferred from the bay laurel to the Daphne species.

Winter daphne flower buds begin to appear in December, biding their time through the coldest months. By the end of February and early March, the buds tire of waiting and begin to open when the weather gets a little warmer. Because it blooms in early spring, daphne is depicted as one of the “San no Kimi”, along with plum blossom and the daffodil.

Daphne flowers appear as a dozen or more florets arranged in an elegant spherical cluster. The flowers of some varieties are entirely white, while others have flowers whose petaloid sepals (daphne doesn’t have true petals) are white on the inside and a reddish purple on the outside, giving the flower cluster a gentle pink hue.

Daphne is considered one of the three top fragrant plants in Japan, along with gardenia (kuchinashi) and fragrant olive (kinmokusei). In connection with its strong scent, its Chinese names translate as “seven-mile fragrance” and even “thousand-mile fragrance”, emphasising just how powerful the fragrance is perceived to be. Daphne’s scent comes from the aromatic compound, daphnin, a plant toxin, and has a fragrance similar to that of agarwood (jinkō), a costly top-grade incense ingredient. The flowers are similar in shape to those of the clove spice flower (chōji). Cloves, incidentally, have long been used in Japan to add fragrance to bintsuke-abura, a traditional hair oil, as well as being used in fragrance sachets, and as deodorisers and insect repellents.

Because of daphne’s similarities to agarwood and clove, the Japanese name for daphne, jin-chō-ge, is actually made by combining the first syllables of jinkō (agarwood) and chōji (clove).

Nanohana (菜の花) – Rapeseed Flower

Plant Family: Brassicaceae.

Botanical name: Brassica napus.

Common Japanese names: nanohana.

Common English name: Rapeseed flower.

Place of origin: Coastal Mediterranean.

Prefectural plant: Chiba Prefecture.

Language of Flowers: Vigour; unexpected encounters.

Rapeseed Flower – More Than Just a Pretty Face

Swathes of bright yellow rapeseed flowers growing en masse in fields and parks throughout Japan delight sightseers from late February through early April. One might be forgiven for thinking this spectacle was created just for sheer enjoyment but, in fact, the rapeseed plant has an important role to play in the health of the Japanese countryside.

Like mustard, rapeseed is grown as a green manure crop. It matures quickly, growing to its full size by early April when farmers are preparing their land for spring planting. The green parts of the rapeseed plant are worked into the soil, where they are broken down by microorganisms to provide nutrients for the crops that follow. Starches and proteins in the stalks and leaves encourage the proliferation of beneficial microorganisms, prompting a flurry of underground activity. This activity improves the soil texture, creating more air-filled pore space and greater moisture retention, all for the benefit of that season’s crops.

Plants grown as green manure crops need to offer more than just nutrients for crops, and there are sound reasons for choosing rapeseed to do this important job. Not only does rapeseed mature in time to be used as a spring green manure crop, farmers have noticed that crops such as sweet potatoes, for example, are less susceptible to disease when grown in soil that’s been prepared with a rapeseed green manure. In common with other brassicas such as mustard and cress, rapeseed contains glucosinolates, organic compounds containing sulphur and nitrogen. Enzymes convert these glucosinolates into isothiocyanates, which in turn work to suppress harmful microbes and nematodes in the soil, providing protection for the roots of the crops.

So clearly, as lovely as it is to look at when it’s in flower, rapeseed is more than just a pretty face!

Text: Osamu Tanaka

Emeritus Professor at Kōnan University, Kōbe. Born in Kyōto, 1947. Studied in the Faculty of Agriculture, Kyōto University, where he earned his doctorate. Post-doctorate activities include a doctoral research fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution (United States), before becoming a lecturer in the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Kōnan University in Kōbe. A prolific author, Dr Tanaka has written many, many books, including Fushigi no Shokubutsugaku (The Wonders of Botany), Shokubutsu wa Sugoi (Plants are Amazing!), Shokubutsu no Himitsu (Plant Secrets), and Zassō no Hanashi (Speaking of Weeds), published by Chūōkōron-shinsha; Nyūmon Tanoshii Shokubutsugaku (Fun Introductory Botany) and Furūtsu Hitotsu-banashi (Tales of Fruit), pub. Kōdansha; Arigatai Shokubutsu (Plants to be Grateful for), pub. Gentōsha; Shokubutsu no Kashikoi Ikikata (Clever Plant Behaviour), pub. SB Shinsho; Shokubutsu no Ikiru Shikumi ni Matsuwaru 66-dai (66 Topics Related to Plant Life Systems), pub. Science Eye Shinsho; and Shokubutsu wa Oishii (Plants are Delicious), pub. Chikuma Shinsho.

Please note: The book title translations in parentheses are literal translations of the Japanese titles, provided for the benefit of our English-speaking readers. These translations are not actual published book titles.