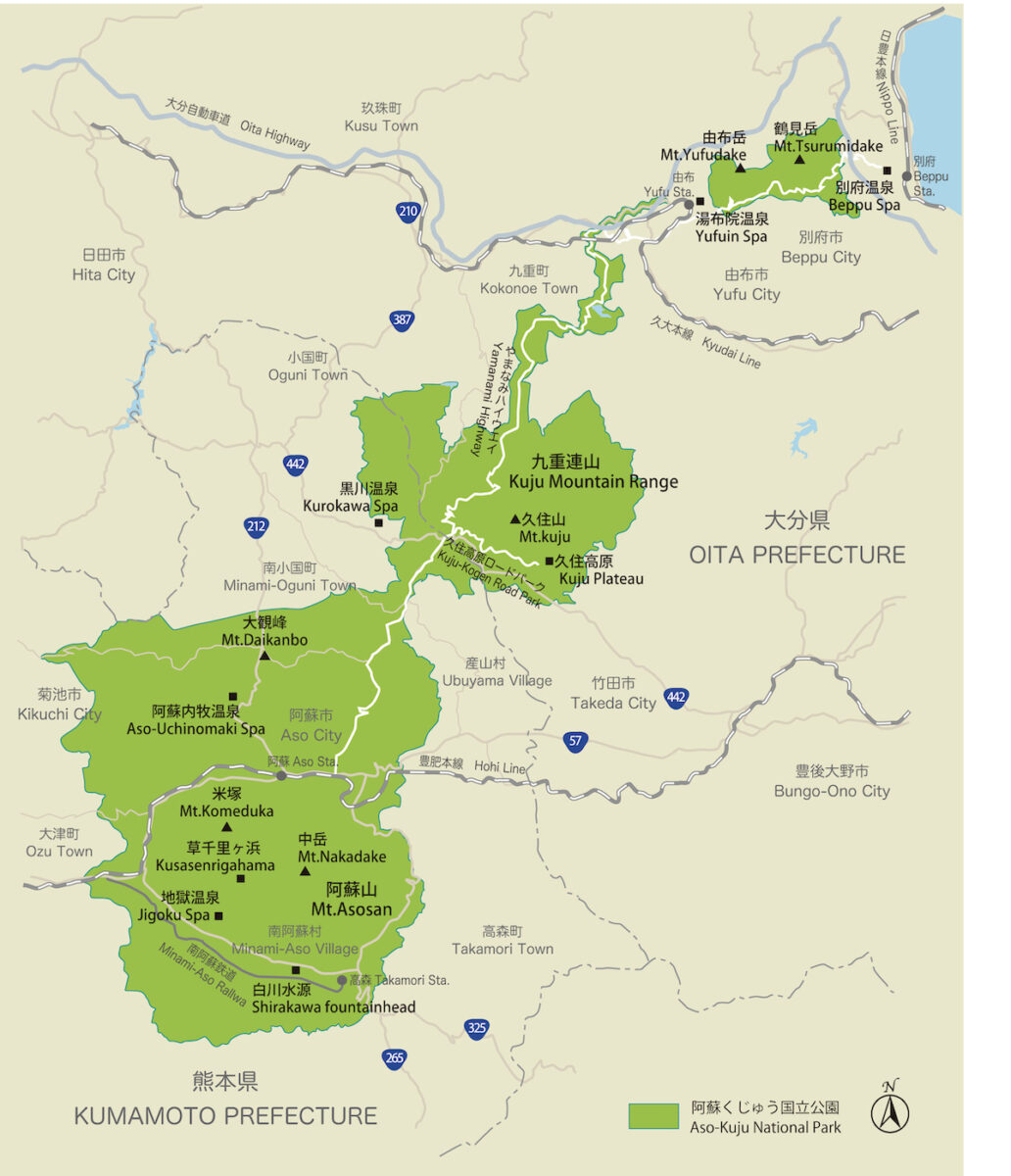

The Aso Caldera, a hollow basin created as the result of volcanic activity, is surrounded by Japan’s most extensive area of grassland. The caldera (the Spanish word for “cauldron”) was formed after magma and gases were ejected from under the ground and the land collapsed into the empty magma chamber beneath. The beautiful landscape of the Aso Caldera rim has been maintained for over a thousand years through a traditional controlled burning technique known as noyaki.

Text : Sasaki Takashi / Photos : 谷口哲 Akira Taniguchi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Noyaki / Akaushi Cattle / Bokuya Guide Project / Visiting Japan's National Parks Series / Farming / Agriculture / National Parks / Aso-Kujū National Park / Controlled burning

Aso’s Vast Grasslands Maintained Through Centuries of Stewardship

Lush grasslands encircle the Aso Caldera, one of the largest calderas in the world. The approximately 22,000 hectares of grassland is comparable in size to the metropolitan area of Ōsaka, Japan’s second largest city.

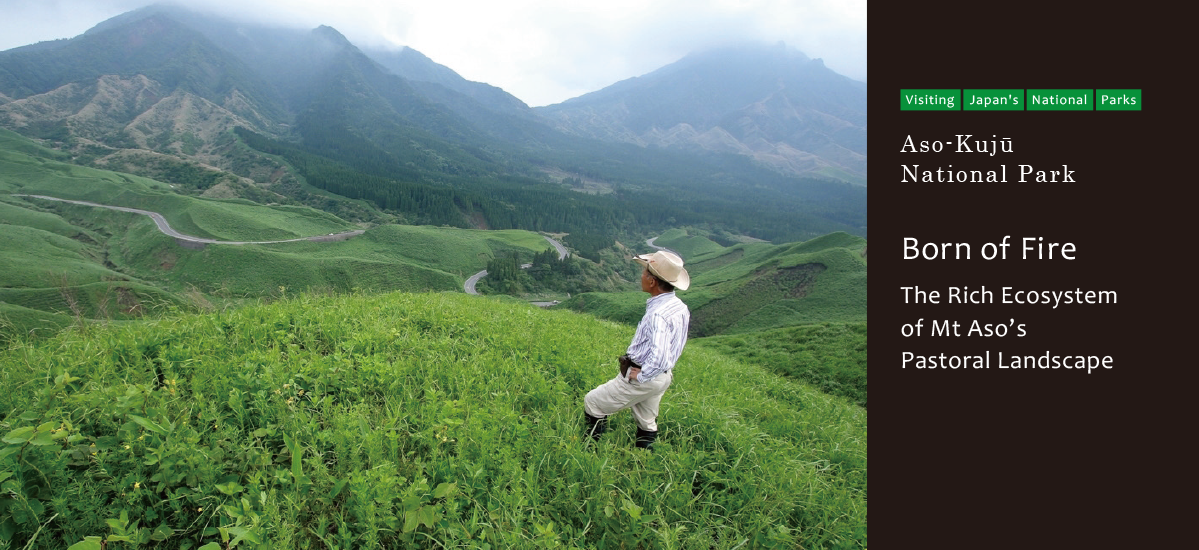

When viewed from elevated spots such as Daikanbō or Kusasenri, the grand scale of these meadows and pastures becomes clearly apparent. Lush grasses ripple in the breeze, a sea of green stretching as far as the eye can see, cloaking the undulating ridges of the caldera rim and the foothills of the caldera’s five central peaks. What makes this quintessential Aso scenery all the more remarkable is that this landscape has been maintained only through centuries of continuous human endeavour.

This is landscaping on a monumental scale.

Keikichi Ichihara, chairman of the Machikoga Bokuya Kumiai, a livestock grazers’ association, explains that without the practice of noyaki (the annual controlled burning that takes place in early spring), the pasture would revert to scrubland within two to three years. To keep the pasture green and lush, continual maintenance is required after noyaki.

As well as raising cattle and growing vegetables in Mt Aso’s eastern foothills, Ichihara san is also involved in a range of activities to educate the public about the importance of the Aso grasslands. His work includes training volunteers to help with noyaki, and taking school children out onto the grasslands to experience the traditional torching of the previous year’s dead grass and weeds. Ichihara san is also involved in the Bokuya Guide project, an initiative that aims to encourage people from all over the world to come and enjoy the landscape. Local guides lead visitors on activities such as cycling and hiking through the grasslands.

The future of Aso’s grasslands is by no means guaranteed. Although a description in the Engi-Shiki (a set of ancient governmental regulations from the Heian Period) shows that this land continues to support a farming lifestyle that dates back over a thousand years, Ichihara san says that the past few decades have seen dramatic changes.

“When I was in my teens,” he recounts, “Aso’s grasslands covered fifty thousand hectares. Now we’re down to less than half that area.”

Ichihara san believes that helping the general public to understand the significance of the grasslands is key to the preservation of this cultural heritage farmland.

Safeguarding the Grasslands for Future Generations through Education

Despite having been born into a farming family and raised amid the grasslands, Ichihara san admits that it is only in the past twenty years or so that he has come to appreciate their true wonder. This realisation began when he took on the task of training volunteers to help with noyaki at a time when a shortage of manpower had begun to make it increasingly difficult for farming associations to carry out the controlled burning without help. The enthusiasm the volunteers had for the grasslands helped him see the importance of the environment he had taken for granted most of his life.

“I learn a lot from the volunteers,” he says. “For instance, there’s a wild plant that grows here called kurara (Sophora angustifolia). Livestock can’t eat it, so farmers just see it as a nuisance. Yet, there’s an endangered butterfly (Shijimiaeoides divinus) that needs this plant to survive, and that’s something I wouldn’t have known, had it not been for the volunteers.”

The Aso grasslands might at first appear to consist of nothing but grass but, in fact, approximately six hundred plant species grow here. The traditional practices of hay mowing and noyaki were originally carried out for farming purposes but one result of the practice was improved airflow and increased sunlight. This enabled the growth of a great variety of flowering plants, and attracted many species of animals, birds and insects.

Ichihara san has an analogy that he likes to make: “Imagine that you had casually picked up a dusty old pebble. After carrying it around in your pocket for ages, you one day discover that it is actually a rare and precious gem! That’s what the grasslands were for me.”

More than just a place of work, the grasslands of Aso are a treasure trove of precious life.

Another thing Ichihara san notices is the mysterious power of the grasslands to unite and heal. He has seen this among school children who come out on field trips to learn about the controlled burning. While some children struggle with learning and behaviour in a classroom setting, Ichihara san has seen them blossom and thrive out in the grasslands, willingly volunteering to help with even the more unpleasant tasks. Bus drivers taking the youngsters back to school after their field trips have commented on how they seem transformed by their experience.

“I’m even more convinced that the grasslands are a treasure for humanity,” says Ichihara-san.

The grasslands themselves are transformed by noyaki. The land is left completely scorched after the controlled burning in early spring. However, new green shoots appear with every fresh shower of rain, and after a month the hillsides glow once more with the fresh green of new life. Without noyaki, the pasture land would remain covered with the dead brown grass stalks left behind by winter.

Aso-Kujū National Park