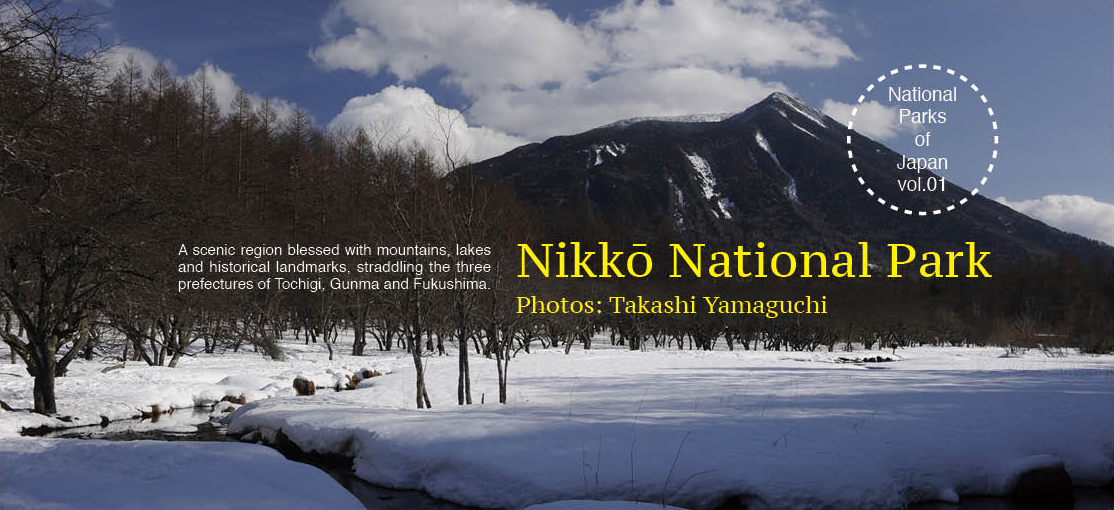

Nikkō National Park, blessed with a remarkable variety of natural features from marshlands and highlands to the lakes and valleys nestled within the peaks of the Nasu Volcanic Zone is set within a scenic region straddling the three prefectures of Tochigi, Gunma and Fukushima. The national park receives a steady flow of visitors throughout the year, drawn to its world heritage sites and the profoundly restful hot springs dotted across the region.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photos : 山口高志 Takashi Yamaguchi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Nikko National Park / Fukushima Prefecture / Gunma Prefecture / Nikko / Tochigi Prefecture / National Parks

Traces of volcanic activity etched into majestic scenery

An active volcanic zone, the remarkably varied and picturesque scenery of Nikkō National Park resulted from the eruptions of three different volcanoes. A stream of heated rocks and ash produced by the eruption of Mt Nantai (2,486 m) in the Nikkō volcanic group dammed the Yukawa River and led to the formation of the Senjōgahara Marshlands and the Ryūzu no Taki Falls (Ryūzu Falls). The same pyroclastic flow also blocked the Daiyagawa River, forming Lake Chūzenji and the Kegon no Taki Falls (Kegon Falls). Interestingly, with a circumference of around 22 kilometres and a depth of up to 163 metres, Lake Chūzenji’s depths far exceed the height of the Kegon no Taki Falls that flow from the lake to the Daiyagawa River below. In contrast to the formation of lakes from rivers, the Senjōgahara Marshlands were originally a lake that became silted up with deposits of sediment and peat and evolved into the wetland area that we see today.

Also in the Nikkō volcanic group, the eruptions of Mt Sannōbōshi (2,077 m) and Mt Tarō (2,368 m), formed the twin lakes Karikomi and Kirikomi, as well as Lake Yunoko, while lava flows from Mt Nikkō-Shirane (2,578 m), the highest peak in north-eastern Japan, led to the formation of Lakes Marunuma and Suganuma in Gunma Prefecture. Far from extinct, Mt Nikkō-Shirane produced rumbles and plumes of smoke as recently as 1952.

Roughly 20 kilometres north-east of the Nikkō volcanic group is the Takahara volcanic group whose most prominent peak is Mt Shakagatake (1,795 m). Exploration of the lava covered northern slopes reveals four eruption fissure vents of up to 300 metres in width and six kilometres in length. Also due to volcanic activity, sedimentary layers of volcanic ash in the nearby Shiobara Hot Springs area, believed to have once been part of the sea, have yielded large quantities of plant fossils.

Journeying another thirty or so kilometres to the north of Takahara, we find the still-active Mt Nasu volcanic cluster, a massif aligned from north to south. Smoke still billows from the western side of Chausu Peak (1,915 m), one of the cluster’s five peaks, and small-scale eruptions were observed there in 1953 and in 1960.

Cherry blossoms and azaleas in spring, autumn leaves in fall: the gloriously coloured four seasons of Nikkō

The varied terrain and differences in altitude from one part of Nikkō National Park to another support a wide variety of plant life. The beech trees, Mongolian oaks and maples in the mixed deciduous broadleaf forests of the foothills give way to fir trees and other conifers once we reach altitudes of 1,600 metres. At over 2,300 metres, we encounter dwarf shrubs and alpine plant varieties. On Mt Nasu in particular, clusters of dwarf stone pine can be seen even below 2,000 metres, giving the area a distinctly alpine feel. Meanwhile, a rich abundance of alpine plants can be found near the summits of Mt Nikkō-Shirane and Mt Nasu, where species such as iwa-kagami (Shortia soldanelloides) and Rhododendron metternichii varieties form plant colonies.

Seasonal changes attract sightseers to Nikkō all year round. In spring, cherry blossoms, deciduous azaleas and Lysichiton lilies are in full bloom. Famed for its wetland areas, one characteristic of this park is the striking plant growth and seasonal variation in its marshlands. From early summer, the marshlands of Odashirohara and Senjōgahara and the western foothills of Mt Nasu are festooned with the fluffy white flowers of cotton grass, as well as the blooms of a remarkable variety of other flowering wetland species.

Nikkō National Park is renowned for its autumn colours, when the mountains and hillsides are ablaze with the crimson foliage of maples and sumac, the yellows and golds of Japanese larch and the burnished tints of wetland grasses. Autumn spans a long period in Nikkō, beginning mid-September in far-flung Yumoto and, as autumn deepens, descending on Senjōgahara by mid-October, before finishing up on the stunning Iroha-zaka Slope where the scenery can be appreciated from the incredible winding roads. Regardless of when in autumn visitors come to Nikkō, it is a safe bet that the autumn colours will be at their peak somewhere in the national park.

Blessed with abundant forest habitat, the park is also home to a variety of wildlife, including Asian black bears, the ‘goat-antelope’ or Japanese Serow, deer and monkeys, and in recent years even wild boar are making a comeback. A bird-watcher’s paradise, the region’s forests, marshlands and ravines are home to around 180 bird species, including many species of waterfowl. In the mountain lakes and waterways the enormous Japanese giant salamander flourishes, and even the distinctive croak of the male Kajika frog can sometimes be heard.

Protecting historic buildings and the natural landscapes that surround them

Historic buildings and sites such as Tōshōgū Shrine and Futārasan Shrine, designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites as part of the ‘Temples and Shrines of Nikkō’, are situated not far from the city of Nikkō and serve as a connection to Japan’s spiritual origins, while the Italian Embassy Villa Memorial Park and Nishi-Rokuban Park on the shores of Lake Chūzenji are reminders of Japan’s early years of modernization in the Meiji period, when foreign diplomats and business people spent their summers here. These sites are now considered the historic cornerstones of the Takahara resort area. And, as to be expected in a geothermal area forged by volcanic activity, plumes of steam rising up from within the many valleys nestled within the national park give away the location of some of Japan’s best hot springs. In this rustic ambience it is not hard to imagine oneself back in the early Heian period, when this area first became renowned for its hot springs, more than 1,200 years ago.

The rich wildlife habitat has, however, created issues for those tasked with preserving the natural landscape, and many of these problems have been posed by the wildlife itself. Numbers of deer have increased significantly, and in certain areas their browsing has led to the disappearance of numerous valuable plant species, while at the same time, plants that are unpalatable to deer, often noxious weed species, have increased in dominance. Tremendous damage has been done to trees and saplings and potential loss of forests is a major concern. As is the growing range and habitat of leeches, which are spread by deer; an issue for not only the agricultural and forestry industries, but also affecting residential areas. In addition, wild boar have been spotted in areas that they have never previously inhabited, and bears and monkeys make frequent incursions into built-up areas.

Governing authorities have responded by constructing fences to try and control the movement of the deer and by attempting to manage their numbers, with one head of deer per square kilometre being the target population. The authorities are also trying minimise the risk posed to both visitors and locals by bears and monkeys by raising public awareness of the dangers associated with contact with these wild animals.

For further information:

Kanto Regional Environment Office

18F, Meiji Yasuda Seimei Saitama Shintoshin Building

Shintoshin 11-2

Chuo Ward

Saitama City

Saitama Prefecture

Japan 330-6018

Phone: 048-600-0516 Fax: 048-600-0517

https://www.env.go.jp/en/nature/nps/park/nikko/index.html