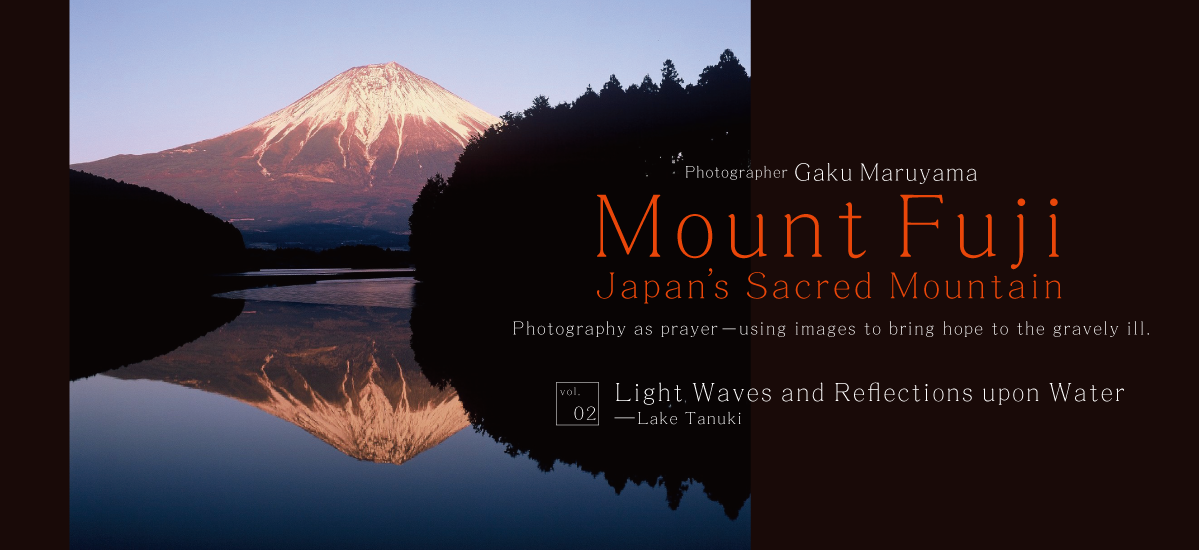

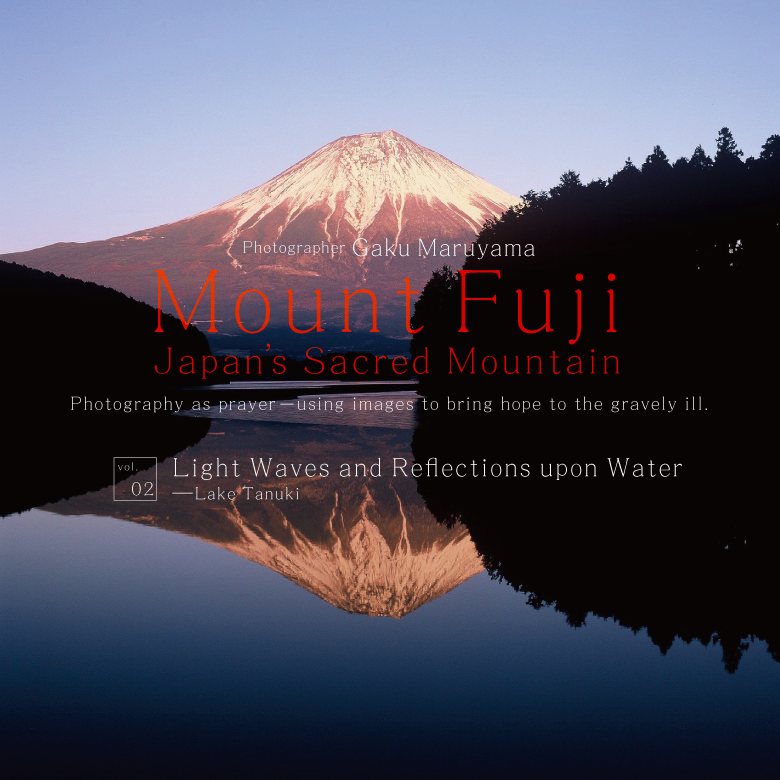

Lake Tanuki is famous for its views of the ‘Diamond Fuji’. In April, and then again in August, the sun rises directly over the apex of the mountain, gleaming as it does so, as if the mountain were a diamond. These days photographers from all over Japan descend on Lake Tanuki in their droves to see this phenomenon – there are even organised bus tours.

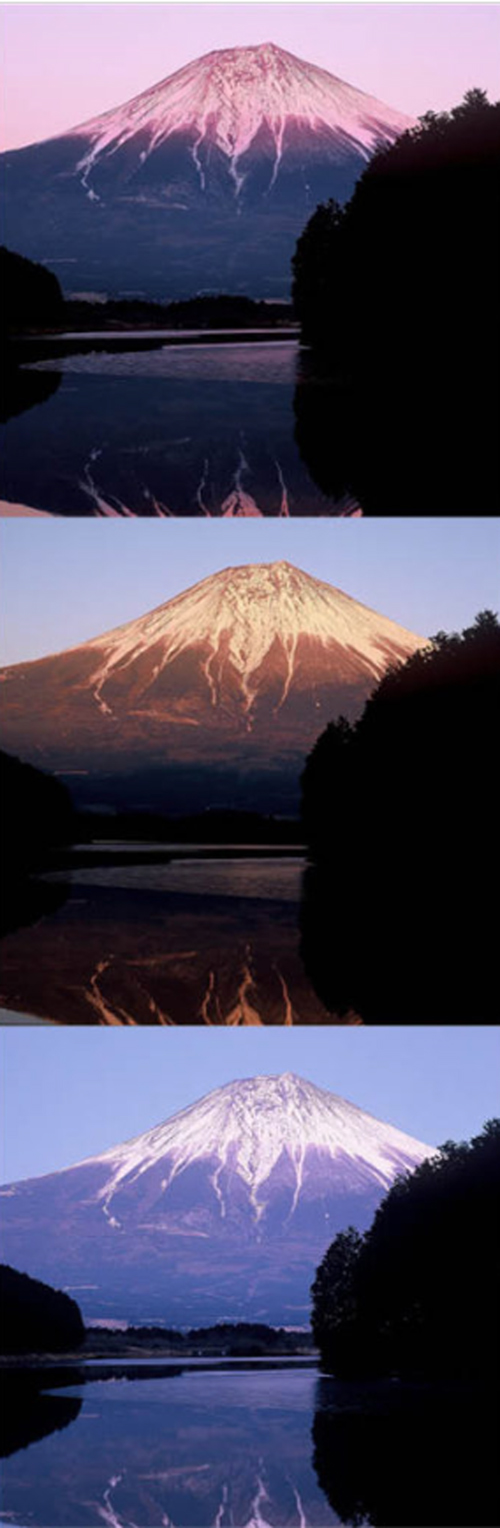

Earlier in the year, visitors come to see the mountain at twilight. From February to early March, the colours change through red, gold and blue as the setting sun catches the snow on the mountain, in a way that is absolutely captivating.

If you’re lucky you might even see Fuji reflected upside-down in the still waters of the lake. Moments such as these offer a calm sense of stillness and clarity. Time seems to slow down and, for a fleeting moment, worldly cares melt away as people feel at one with nature.

Photos and Text : 岳 丸山 Gaku Maruyama / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : photography / Mount Fuji Photography Series / Lake Tanuki

Capturing Mount Fuji

Anyone who photographs Mount Fuji over the years is bound to encounter various natural phenomena that will give cause for wonder. I had a moment like this at Lake Tanuki, where I experienced first-hand the theory of light wavelength.

From late January to early March, conditions for photographing Mt Fuji are at their peak. The colder it is, the clearer the atmosphere, and the sharper the light. Here at Lake Tanuki, a once-a-year marvel reveals itself during that time. On Japanese TV programmes about Fuji they often talk about ‘miraculous scenery’, but a lot of that’s just tired old clichés. What I’m talking about is the real thing!

The curtain rises on the drama just before sunset and the scene continues to play out for around 20-30 minutes after the sun has gone down. The colour of the mountain changes depending on the wavelength of the visible light – the longest wavelength being red and the shortest, violet. The arc of the rainbow has these wavelengths nicely lined up from longest at the top of the arc, to shortest at the bottom: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. When the wavelength of light is longer or shorter than the visible light spectrum, then that light is invisible to humans. During the mid-winter twilight at Lake Tanuki, you can actually experience the phenomenon of the different light wavelengths with your own eyes.

I’ve been lucky enough to come across this scene just once. In early February, when the weather was really cold and the skies were crystal clear, I judged my chance had come and headed for Lake Tanuki. It takes about an hour from my house to Lake Tanuki, which is near enough for me wait at home until I’m certain the weather conditions are right, and still get there in time. However, I hadn’t taken the crowds into account! When I got to the lakeside observation deck where I’d intended to set up my gear, there was already a huge crowd of people there. Trying not to be rude or pushy, I slowly inched my way to a spot at the very front, taking advantage of every little gap that opened up for me. There were photographers there of varying degrees of experience – you can tell how long people have been doing this by looking at their tripods!

Once I’d made it to where I wanted to be, I set up my camera and waited for the big moment. First came the red light, the longest wavelength, colouring the snow on the top of the mountain pink. Next, a distinct change and the yellow light appeared, making the snow sparkle with gold. The light continued to subtly change colour until it began to fade.

Having captured the red and gold, and quite pleased with myself, I was making preparations to return home, along with everyone else. After all, that’s what we’d all come for. Just then though, the elderly photographer beside me gruffly said, ‘Just wait a bit longer, you! There’ll be another colour change’. By this time, most people had finished taking photos and were leaving, satisfied with their efforts. Apart from the elderly gentleman and me, only a handful of others remained on the deck.

After ten or so minutes more, I suddenly understood what the elderly photographer had meant. The colours on Mt Fuji’s snowy peak, which had been cooling down to a monochrome, gradually began to change again. This time to a brilliant indigo. Not just the snow on the mountain, but the entire atmosphere was bathed in blue. Right there in front of my eyes was a scene I had never come across before, not even in a photo.

While I do more or less understand light wave theory, this was the first time I’d ever seen such vivid colouration. I would have expected the colours to change smoothly, one after the other, as the wavelengths changed – so why did we have to wait for over ten minutes before the final colour appeared? Is there something about the topography of Lake Tanuki that causes this? Does Lake Tanuki somehow cause the light to refract in a unique way? Or is this just how long it takes for the light to change from yellow to indigo? I still haven’t found a satisfactory answer to these questions. And I’ve been trying and trying to capture this phenomenon ever since, but as yet I’ve had no luck.

There are plenty of views all around Mt Fuji that are so spectacular they’ll cause you to doubt your own eyes. I’m sure that photographers who’ve been taking pictures of Mt Fuji for years must have encountered these spectacular scenes any number of times. And I’m also pretty sure that this is what lures these people back to the mountain time and again, day in and day out.

Mt Fuji – Japan’s sacred mountain – is addictive!