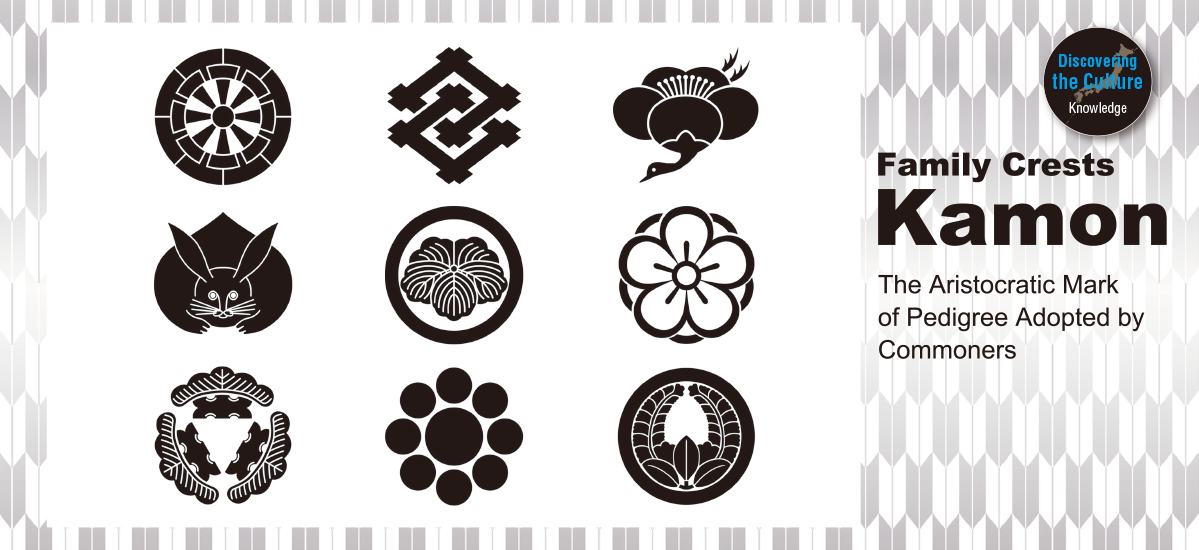

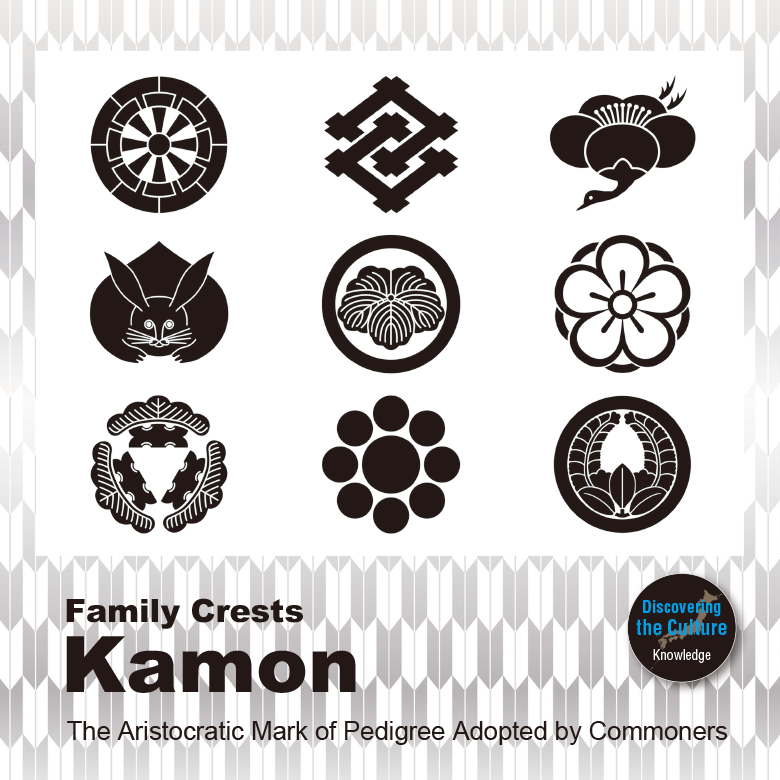

Japanese graphic design abounds with symbolic motifs. Notable among these are “kamon”, family crests that represent a family or an individual. While some kamon serve a similar purpose as the coats of arms used by European nobility, what is seems to be unique to Japan is the fact that here, family crests are widely used at all levels of society, among commoners and nobility alike.

Text : 中島有里子 Yuriko Nakajima / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Edo Period / Edo Design Series / Kamon / Family Crests

The Unique Design Culture that Flourished During Japan’s Edo Period

Originally used as decorative markings for household items such as furniture and tableware, kamon came to be used to indicate an individual’s family pedigree and social status.

During the Heian Period, kamon came to be used by the aristocracy as a display of their aesthetic aspirations and authority. Distinctive motifs were developed, such as the swirling comma-shaped “tomoe” emblem and the “mokkō” emblem based on the quince blossom.

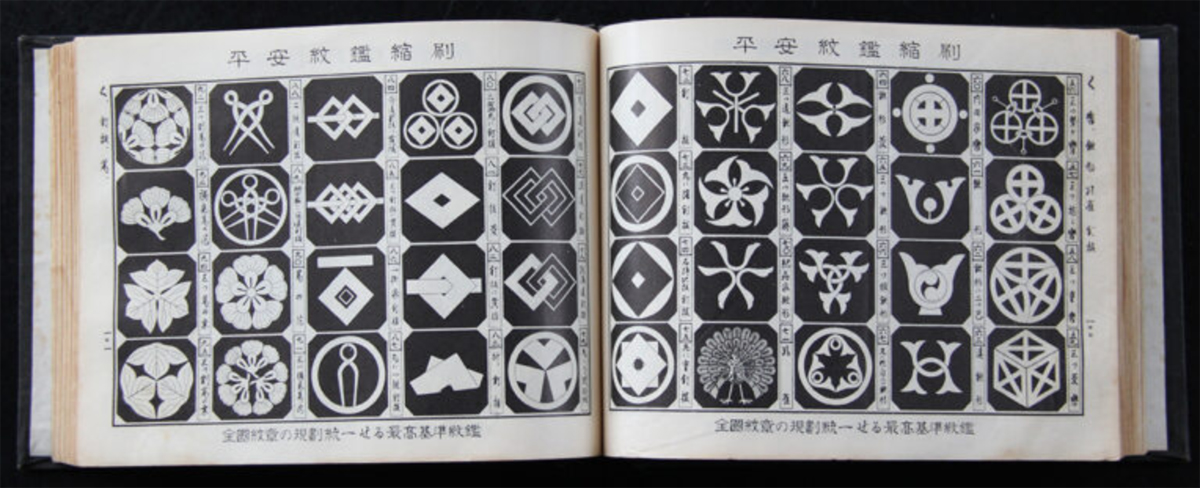

When power shifted from the aristocracy to the military samurai class during the Kamakura Period, a practical way of differentiating the often-warring samurai clans from one another was needed. In order to distinguish themselves and draw attention to their own performance on the battlefield, clans adorned their battle standards and marked out their camp enclosures with striking symbols. These needed to be simple enough that they could be quickly and accurately painted by hand on the battlefield, and distinctive enough to be easily recognisable. Examples are the Ashikaga Clan’s double-stroke “futatsu hikiryō-mon” crest consisting of two horizontal lines contained within a circle, or the Shimazu clan’s “marujūji-mon” crest – a plus sign inside a circle. By the middle of the Kamakura Period, family crests had become an established part of samurai culture, with almost all samurai families having their own crests.

Once the samurai had overthrown their aristocratic masters to become the ruling class, social stratification between the four official non-aristocratic classes (comprising samurai, artisans, farmers and merchants) was strictly adhered to and social mobility between these classes was forbidden. Samurai family crests, representing elite social status and family lineage, came to be synonymous with power and authority.

During the two and a half centuries of peace ushered in by the Edo Period, and in the absence of any need to distinguish oneself on the battlefield, samurai families decorated their distinctive formal attire such as haori (short coats) and kamishimo (two-piece ceremonial dress consisting of sleeveless overvest with extended shoulder pieces and matching hakama trousers) with their family crests. This is when the use of kamon started to spread among common folk. While the public use of family names was forbidden to the non-samurai commoner classes at this time, there was no law one way or the other regarding the use of kamon, and the use of these family crests was eagerly adopted by all commoners seeking to distinguish themselves.

By the end of the 1600s, after close to a century of peace under the reign of the Tokugawa shogunate, not only successful merchants and wealthy farmers, but even the most ordinary peasants, townspeople and artisans were using family crests. Popular entertainment flourished during this time and ukiyo-e paintings depicting actors and courtesans were widely circulated and much sought after. Kabuki actors began to sport crests to show which house they belonged to and these emblems were handed down through various theatre families, along with performance techniques and traditions. Large crests were even added to theatrical costumes, distinguishing the actors from the story, catching the eye of the common folk and enhancing the prominence of popular actors.

The Second Paris International Exposition of 1867 saw the introduction of Japan’s kamon designs to a European audience. The simple yet powerful motifs featured on clothing, swords and furnishings immediately struck a chord with audiences, becoming part of the Japonisme craze. It’s even speculated that the iconic Louis Vuitton monogram, composed of geometrically arranged stylized flowers and letters and which debuted in 1896, may have been inspired by Japanese family crests introduced to the West at the Paris Exposition.

In modern day Japan, kamon are employed as logos for commercial enterprises and public organisations, and are recognised the whole world over. Mitsubishi Corporation’s three-diamond emblem, chosen by Mitsubishi founder Yataro Iwasaki, combines the three stacked rhombuses of the Iwasaki family crest and the triple-leaf crest of the Yamauchi family, Yataro Iwasaki’s first employer. Meanwhile Japan Airlines’ red-crested crane in flight (resembling a Mōri clan crest and designed 1958 by Jerry Huff of the airline’s American advertising agency) is a familiar and welcome sight to travellers to and from Japan.

There are thought to be over five thousand distinct types of kamon in Japan, a tradition that continues into the present day. These uniquely Japanese and deceptively simple visual symbols embody centuries of historical bloodlines and family ties.