In this series we explore the four seasons in Japan and the poetic nijūshi sekki (twenty-four seasonal divisions) of Japan’s ancient calendar, expressed in the waxing and waning of the moon and the movement of the sun across our skies.

Text : 鈴木充広 Michihiro Suzuki / Illustrations : Aso Yuriko / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Japan’s Ancient Calendar / Japan's Ancient Calendar Series / New Year / Traditions

Vol.02. Setsubun and the New Year

The Western calendar is so much a normal part of Japanese life nowadays that hardly anyone ever gives it a passing thought. However, when one stops to think about where traditional events or the changes of the seasons sit on the calendar, here in Japan there’s a sense that they don’t quite fit as they should. For example, the characters 新春 (shinshun), meaning ‘new spring’, are often written on New Year’s decorations and greeting cards, but this seems to make no sense at the beginning of January when winter is just getting underway.

This state of affairs came about because of the calendar reform that saw the adoption of the Western (Gregorian) calendar in 1874, as part of the Meiji Era (1868 – 1912) drive to modernise Japan. The adoption of the Western calendar resulted in New Year’s Day, which in the traditional calendar had coincided more or less with the beginning of spring, being shifted to January 1st.

New Year in the Kyūreki – Japan’s Old Calendar

For over a thousand years prior to the Meiji reforms, Japan had followed the old kyūreki calendar, also sometimes referred to as the risshun-shōgatsu calendar. Risshun means the start of spring, and shōgatsu is the new year. The use of the term, risshun-shōgatsu, indicates that according to this traditional calendar, the start of the new year coincided with the beginning of spring. This contrasts with the Gregorian calendar, which places New Year’s Day soon after the winter solstice, which occurs in late December.

The timing of New Year’s Day in the old kyūreki calendar was, however, quite variable. Although we tend nowadays to think that the beginning of the year always coincided with the beginning of spring in the kyūreki, closer examination of the old calendar reveals that this was not always the case. In fact, the timing of New Year’s Day (determined by the phases of the moon) could fluctuate by as much as two weeks either side of the beginning of spring, which is determined by the position of the sun. Nevertheless, it’s safe enough to say that New Year’s Day occurred at approximately the same time as the beginning of spring, which is why spring greetings were offered along with New Year’s greetings in the old days.

Risshun and Setsubun

So, where does Setsubun fit into the scheme of things? Risshun is the day traditionally designated as the first day of spring and Setsubun is the day before that – ‘Risshun Eve’, if you like.

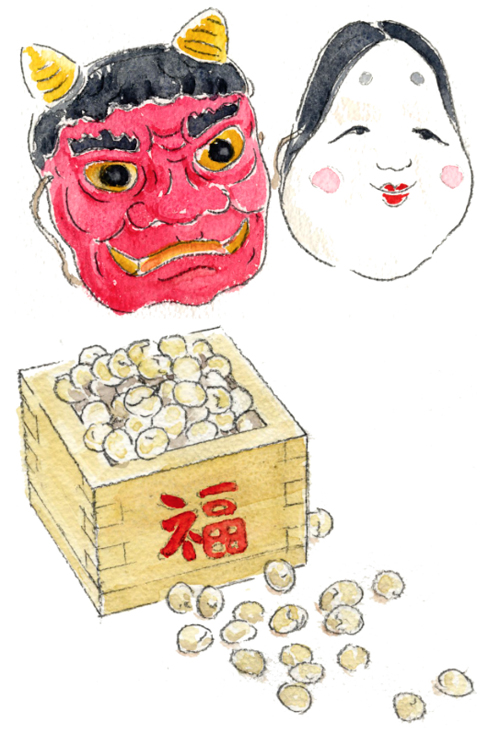

Although it isn’t a holiday, Setsubun, observed at the beginning of February, is when families all over Japan celebrate with special food and boisterous rituals. Children chant “Oni wa soto! Fuku wa uchi!” (Demons out! Good fortune in!), while throwing roasted soybeans out the front door to drive out evil spirits and bad fortune. Adults dress up as oni (demons), much to the delight of the little ones who get to throw beans at them. Setsubun has now completely overshadowed risshun, which isn’t really marked by any special events at all.

An often forgotten fact is that Setsubun actually occurs four times a year. The literal meaning of ‘setsubun’ is ‘division of the seasons’ – Setsubun is a day inserted between the seasons to mark them off from each other. Accordingly, there is a Setsubun the day before rikka (立夏 traditionally the first day of summer, approx. May 6th), before risshū (立秋 first day of autumn, approx. August 8th) and one before rittō (立冬 first day of winter, approx. November 8th).

Rituals that were (and still are) enacted at Setsubun such as mame-maki (bean throwing), or yaikagashi (placing grilled sardine heads and holly at the entrance to the house), were intended to ward off malign energy that might prevent the coming of spring. All four Setsubun days throughout the year would have been celebrated in some similar way in the past, but sadly all that remains now is the spring Setsubun, the other three having been forgotten over time.

Setsubun and New Year’s Eve

At some point in the distant past, Setsubun, a spring rite, also became a de-facto end-of-year ritual, because it so often coincided with the traditional New Year’s Eve. Similarly, this Setsubun-New Year’s Eve cross-pollination meant that in return, some of the year-end rites came to be associated with Setsubun, rather than with New Year’s Eve.

One such end-of-year ritual that has now come to be associated with Setsubun is the driving out of demons. There used to be a ceremony on the last day of the year called oniyarai (banishing the demons), during which ‘demons’, symbols of any shame or disgrace incurred during the year, were cast out. This ritual, which originated in tsuina (追儺 a court ceremony to drive out evil spirits) allowed everyone to start the new year with a clean slate, at least in a spiritual sense.

A separate practice that was part of Setsubun rituals to welcome spring involved scattering soybeans, symbols of new life and the approaching spring. At some point these two separate rituals got combined, so that we now throw the beans at demons during Setsubun!

Even the massive ehō-maki sushi rolls that have recently become a popular part of Setsubun have a connection with former New Year’s rituals. Ehō means ‘lucky direction’. At the end of the year in the old days, people would conduct a ceremony dedicated to Toshitokujin (the goddess of lucky directions) to welcome in good fortune (hence the ‘fuku wa uchi’ chant we now hear at Setsubun). Again, this is another rite that originated as a New Year’s ritual and has now become a beginning-of-spring ritual.

Setsubun and New Year’s Eve in the Modern Era – Even the Demons are Confused!

There were certain years in the kyūreki when New Year’s Day and risshun (the first day of spring) did coincide, so logically, Setsubun and New Year’s Eve would have occurred on the same day in those particular years as well. Even when they didn’t coincide though, the two festivals were generally only a few days apart. So, given that they occurred at around the same time and had a similar purpose, it’s hardly surprising that spring rites and New Year’s rites got a bit muddled.

However, now that New Year’s Day is celebrated on January 1st and Setsubun not until a whole month later, New Year’s Eve ceremonies such as the casting out of demons and the welcoming in of fortune have become disconnected from year-end festivities both in time and in significance, and are only ever thought of now as Setsubun rituals.

As our rituals and ceremonies take on new characteristics and change in accordance with the modern calendar, there may come a day when we no longer even know why we banish demons or eat ehō-maki during Setsubun. And what of the poor old demons themselves? They must wonder why they keep getting chased out of the house when it’s not even New Year’s Eve!