It is only natural that Japan, a land richly endowed with majestic natural features and an abundance of changing seasonal colour, should be perfectly suited to the creation of beautiful gardens. These gardens, inspired by nature, religion and the intellect, are reflections of the people who created them and the societies in which they lived. The gardens of Japan provide a fascinating window into the wider spiritual and intellectual principles that underpin their creation.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photos : 中田勝康 Katsuyasu Nakata / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : UNESCO / Temples / History / Heian Period / Japanese Gardens / Mōtsū-ji Temple / Iwate Prefecture

Garden Splendour Reflects Dreams of Paradise on Earth

Towards the end of the Heian Period (794 – 1185), there briefly flourished a dazzling Buddhist culture in far flung Mutsu Province. The rulers of this northern province were the Ōshū Fujiwara, the northern branch of Japan’s ruling clan. For around a century, successive generations of Northern Fujiwara drew on their fantastic wealth to build an ideal realm modelled on the principles of Buddhism. Vast resources were pumped into the restoration of the existing Chūson-ji and Mōtsū-ji temples, two of the jewels in the crown of their glittering political and administrative capital Hiraizumi, in modern-day Iwate Prefecture.

The Mōtsū-ji Temple complex was built by second generation Lord Motohira and third generation Lord Hidehira. The site, one of five historic sites in Hiraizumi associated with Japanese Pure Land Buddhism, was granted UNESCO World Heritage site status in 2011. Mōtsū-ji was originally a magnificent Buddhist temple complex comprising a myriad of buildings including forty temples and living and meditation quarters for 500 monks. A large-scale garden was created within the complex, based on the cosmology of Pure Land Buddhism. Pure Land gardens were also created at nearby Kanjizaiō-in and Muryōkō-in temples at around the same time, although for some reason the garden at Chūson-ji Temple was never completed.

The Northern Fujiwaras’ attempts to create an earthly paradise came to an end at the beginning of the Kamakura Period (1885 – 1333), when the clan was defeated by Minamoto no Yoritomo. Tragically for lovers of historical architecture and landscape design, the Mutsu Province realm was laid waste, its glittering capital entirely reduced to embers. The Edo Period poet Matsuō Basho, upon visiting the province in 1689, lamented the pointlessness of the destruction that had taken place there.

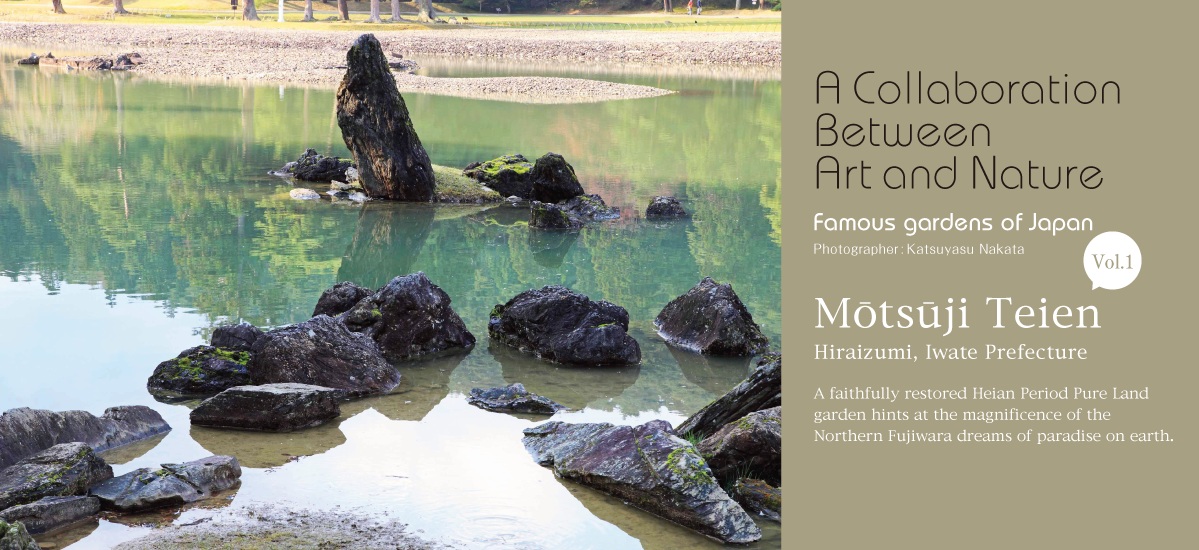

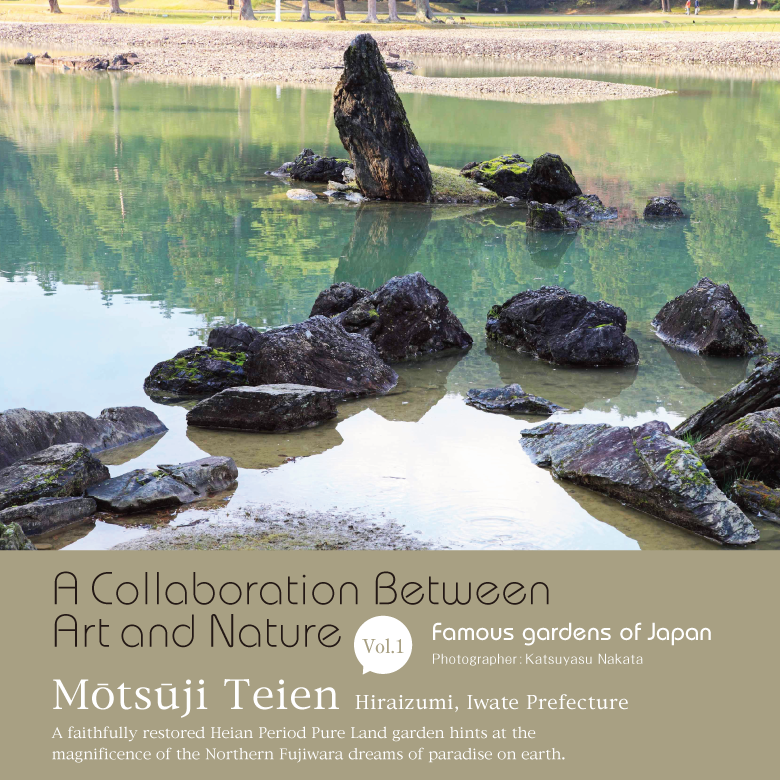

Graceful Curves of the Pond Accentuated by Carefully-Placed Rocks

The grounds of Mōtsūji lay neglected for centuries until archaeological work began in the 1950s. Analysis revealed that the site had once been a magnificent temple complex consisting of a main temple hall surrounded by a numerous other temple buildings. The garden was found to contain a large pond, Izumi-ga-Ike, with two islands. Although little now remains of the original main hall other than its foundation stones, it was accessed by bridges that lead from the great south gate across the pond via the central island, linking the world of people to that of paradise.

Later analysis revealed that the circumference of the pond was constructed to resemble a beach, entirely paved with small, round rocks. Excavations on the eastern side of the main hall uncovered a Heian-style yari-mizu watercourse. This narrow, slightly meandering stream, 70 metres long and around 1.5 metres wide, flows once again into the pond from the north.

The shoreline of Oizumi-ga-Ike pond describes a series of loose curves. On the southern banks several groupings of rocks have been placed to represent the windswept and weathered rocks of the Iwate coast. On a small rocky islet further out in the pond, a standing rock set on an angle creates a powerful dynamic and serves as a focal point from several different parts of the garden. The eastern banks of the pond were constructed to resemble gracefully curving rocky shoals. A karesansui-style stone garden on a rocky outcrop constructed on the south-western bank creates interest, contrasting with the gentle curves of the pond.

The restoration of Mōtsūji Teien was completed in 1992. Although little remains of the former magnificent temple complex, the faithfully restored garden is one of the few preserved Heian gardens in the country. As befits the historical significance of this garden, Mōtsūji Teien once again plays host to a series of seasonal events and festivities, recreating the pomp and splendour of the Heian Period.

Mōtsūji Teien Garden

Heian-style chisen senyū-shiki Buddhist Pure Land garden/ historical landmark/ place of special scenic beauty

Address: Ōsawa-58, Hiraizumi-chō, Nishiiwai-gun, Iwate Prefecture 029-4102

Phone: 0191-46-2331

Website: http://www.motsuji.or.jp/en (In Japanese and English)

Hours: 08:30 – 17:00 (08:30 – 16:30 from November 5 to March 4)

Admission: 500 yen

Access: JR Tohoku Main Line – 10 minutes on foot from Hiraizumi Station. Tōhoku Expressway – approx. 10 minutes or 3 km from Hiraizumi-Maesawa Interchange.