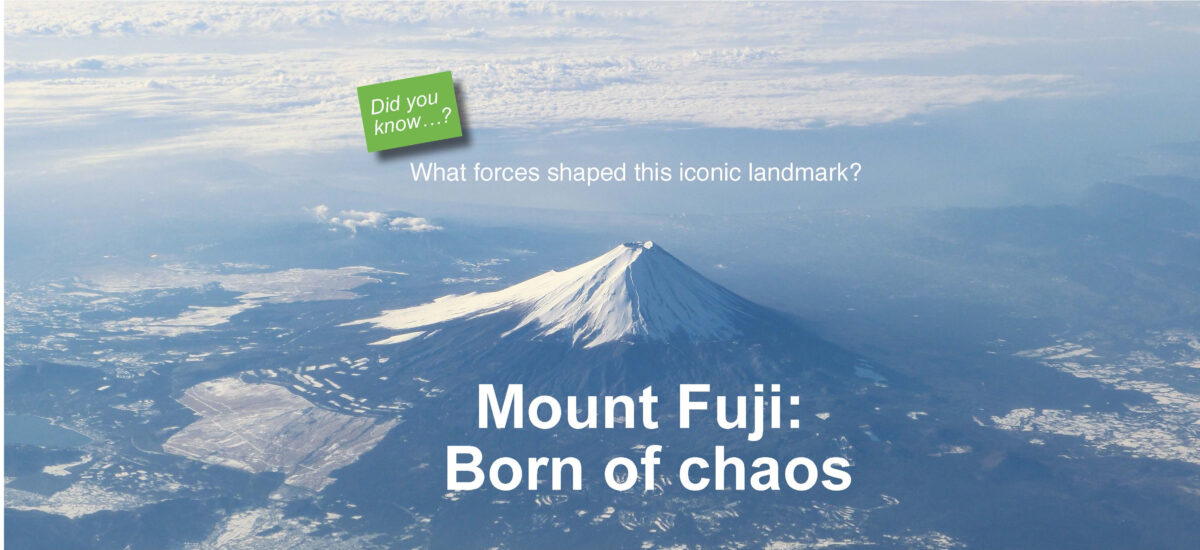

The muse of so many poets and artists, Mount Fuji rises gracefully above her foothills. Bearing the marks of her violent origins all over her body, this vast mountain is a testament to the wonders of nature.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Mount Fuji / World Heritage Sites / Volcanic Activity / Volcanic Eruptions / Landforms

The hidden secrets of Mount Fuji, one of Japan’s most iconic symbols

Mount Fuji’s gracefully symmetrical cone actually conceals three volcanoes buried within. The process of forming the mountain that we know today as Mount Fuji began several hundred thousand years ago with the eruptions of the Mount Hakone and Mount Komitake volcanoes.

At the 5th Station, on the northern slopes of Mount Fuji, the horseshoe-shaped remains of a crater can be seen near Komitake Shrine. This is the peak of the now-buried Mount Komitake. This peak is around 2,300 metres above sea level, but Mount Komitake is thought to have been much higher than that immediately after its eruption. Hundreds of thousands of years of erosion have led to Mount Komitake’s present reduced height.

Approximately eighty thousand years ago, the volcano known as ‘Old Fuji’, on the southern slopes of Mount Fuji, erupted, with intense volcanic activity, often accompanied by massive mud and rock flows, continuing until as recently as ten thousand years ago. Volcanic ash settled over the whole of the southern Kantō area, leading to the formation of the Kantō loam layer. The height of Old Fuji at that time is thought to have been 3,000 metres, but it has since eroded to its present-day height of 2,700 metres.

The present-day Mount Fuji, referred to by geologists as ‘New Fuji’, was formed by volcanic activity that began around one hundred thousand years ago. New Fuji began energetically belching forth mud, rock and ash which all but buried its smaller neighbours, Komitake and Old Fuji, gradually forming the composite volcano that was to become Japan’s highest mountain. The extended sweep that forms the base of Mount Fuji resulted from the gradual build-up of huge amounts lava and debris that flowed from New Fuji and her two adjacent volcanoes. After resting for a period of three to four thousand years, volcanic activity resumed, to form the mountain that we see today.

This unique symbol of Japan also belongs in a category of its own within the field of volcanology. Lava from most volcanoes in Japan is slow-flowing andesitic lava, but unusually, the lava that flowed from Mount Fuji’s composite volcanoes was fast-flowing basalt lava, which shaped the spreading curve of the base of the mountain, and also left curiosities such as lava caves and lava tree moulds that can be seen today.

Mount Fuji’s last eruption, on the heels of a catastrophic earthquake

Mount Fuji’s volcanic activity has continued since the beginning of recorded history, with a dozen or so confirmed eruptions occurring as recently as the mid-Edo Period (1603 – 1868). The first eruption on record took place in 781, and is mentioned in the Shoku Nihongi national history completed in 797: ‘Ash rained down on the land of Suruga, causing the leaves on the trees to wither…’ Records show that the eruptions that occurred in 800, 864 and 1707 were particularly devastating. These are collectively referred to as ‘the big three eruptions’.

The eruption from the crater at the very top of the mountain in 800 continued for a month. Days of darkness were followed by nights where the skies were ablaze with the light of the flames, and huge volumes of volcanic ash were belched into the sky, to the accompaniment of thunderous rumblings. As the ash settled, it buried the Ashigara Pass which connected East and West Japan. Two years later, the new Hakone Pass was opened.

The eruption of 864, according to records from the old Suruga Province to the south of the mountain, was accompanied by a medium-intensity earthquake. The records mention that the eruption continued unabated for more than ten days, with rocks falling from the sky like rain. Meanwhile, lava flowed down the north-western flank of the mountain into Se-no-Umi Lake, splitting this large lake into three smaller ones, known today as Lake Motosu, Lake Shōji and Lake Saiko. Interestingly, the water level across these three lakes is always the same, and it is thought that they remain connected by underground waterways.

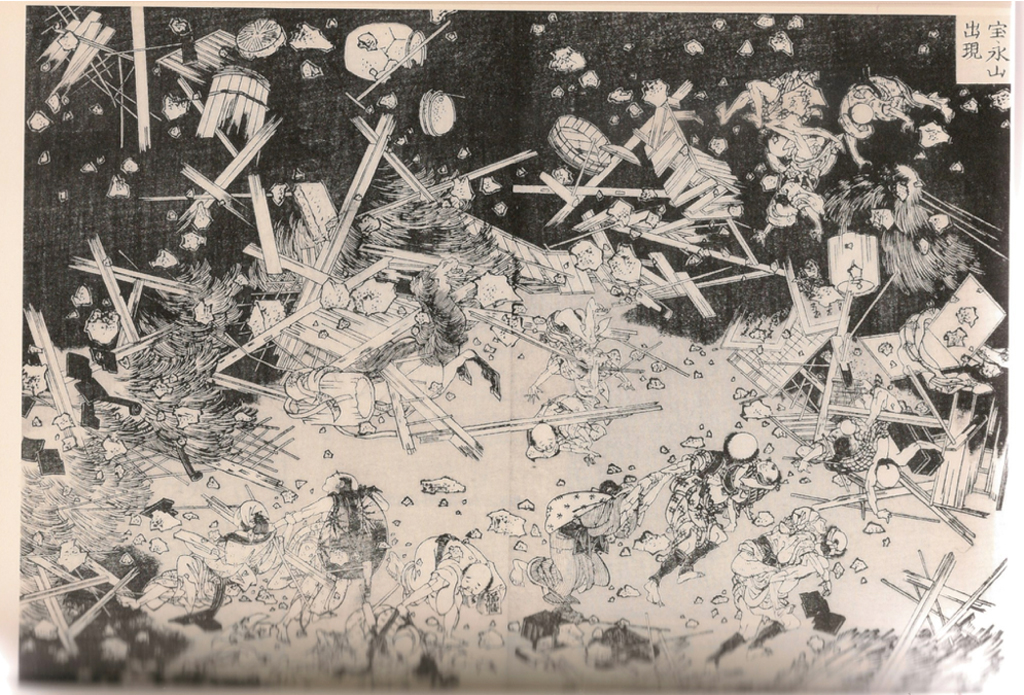

Mount Fuji’s most recent eruption was in 1707. Pumice and ash fell all over the southern Kantō region, and magma forced sediment up from underground, forming the volcanic cone adjacent to Mount Fuji that we now call Mount Hōei. Two months before the eruption, in October, a catastrophic Magnitude 8 earthquake had occurred in the Tōkai area, followed by swarm earthquakes. In December, loud reverberations were heard, and plumes of smoke began to billow from the south-eastern flank of Mount Fuji, continuing for more than two weeks. Volcanic ash is recorded to have fallen as far afield as the city of Edo (present-day Tokyo), covering the city in a layer of ash more than a centimetre thick.

Most records of these volcanic eruptions are based on official histories or journals from temples and shrines, however, researchers note that well-known works of literature such as the Man’yōshū and the Sarashina Diary also contain fascinating descriptions of the eruptions.

The Hidden Charms of an Active Young Volcano

Evidence of Mount Fuji’s long period of volcanic activity is scattered in various forms all about the flanks of this vast mountain. The Fuji Five Lakes that extend from the north-eastern part of Yamanashi Prefecture to north-western foothills were formed as the result of dams created by lava flows. As there are no significant rivers flowing into these lakes, it is thought that they maintain their water level from ground water that flows from beneath Mount Fuji itself.

Among the most interesting curiosities that have resulted from Mount Fuji’s volcanic activity are the lava caves and lava tree moulds. Lava caves generally only form within basalt lava, and in Japan they are most concentrated here at Mount Fuji. The longest of the caves, more than two kilometres in length, is Mitsuike Cave near Fujinomiya City, Shizoka Prefecture. Caves form during a lava flow, either when pockets of volcanic gas form large ‘blisters’ within the lava, or when the outer surface of the lava flow solidifies, forming a tube that the still-molten lava continues to flow through. Once the lava has ceased to flow, the hollow tube remains.

Lava tree moulds occur when lava swallows a forest. As the engulfed trees are incinerated within the hardening lava, tree trunk-shaped cavities are left in the solidified rock. Trees that were standing when they were encased leave vertical cavities, while trunks that were lying on the ground leave horizontal cavities. Some of the lava tree moulds on the Yamanashi Prefecture side of the mountain measure more than three metres in diameter, but most of them are in the range of around one to two metres across. Lava caves and tree moulds provide scientists with useful information such as the direction and speed of the lava flow and its level of viscosity, as well as information about the type of vegetation that was present at the time of eruption.

Aokigahara Forest, in the north-western foothills, is a primeval forest growing on top of hardened lava from the 864 eruption. Because of the low fertility of the soil here, plants take a long time to establish, and the area is covered with predominantly coniferous forest. Curiously, the lava rock underfoot is magnetic, so can potentially play havoc with a compass if it is close enough to the ground..

Mount Fuji is still a young, active volcano and plenty of questions about its volcanic mechanisms remain unresolved. With so much yet to discover, the results of future research are eagerly anticipate