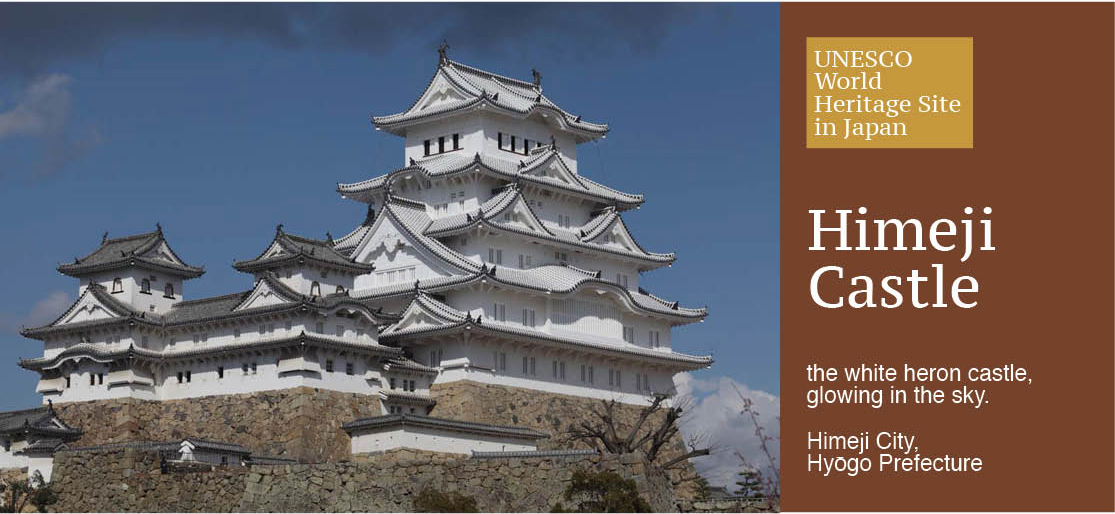

Himeji Castle is considered a masterpiece of early 17th-century Japanese castle architecture. Despite the castle’s elegant external appearance, its complex defence system reveals the castle’s intended function as a strategic military fortress. The significant features of the large scale construction of the early 1600s are still beautifully preserved, and in 1993 Himeji Castle was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photos : 青柳健二 Kenji Aoyagi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Japanese Castles / World Heritage Sites / Himeji Castle / White Heron Castle / Japan World Heritage / Edo Period / History / Hyogo Prefecture / Samurai

An impregnable fortress built to suppress the power of the Toyotomi and their supporters

With its soaring towers and turrets and its pristine white-plastered exterior, Himeji Castle has been likened to the graceful white heron, from which it takes its nickname, Shirasagi-jo (White Heron Castle). In every season and from any vantage point, rising up into the blue sky or riding on waves of cherry blossoms, the castle’s majestic appearance never fails to impress.

Himeji Castle’s present-day appearance was established at the beginning of the Tokugawa Shogunate in the 1600s, but its history as a castle dates back much earlier. In 1333, provincial governor, Norimura Akamatsu, is thought to have built a fortress on Himeyama hill, where the main keep is now located. After that, the ownership of the castle transferred rapidly from one family to another. During the Warring States Period (1467-1603), Hideyoshi Toyotomi took over the castle and set about fortifying the site with a stone wall surrounding a three tiered castle, with the intention of making this his frontline base.

After the defeat of Hideyoshi at the Battle of Sekigahara, Shogun, Ieyasu Tokugawa, consolidated his rule over the entire country. To keep a close watch on the daimyō (feudal lords) of western Japan who maintained allegiance to Hideyoshi, Ieyasu required that they and their retainers and soldiers, along with daimyō from all over Japan, spend alternate years in the new capital at Edo (modern-day Tōkyō). Himeji was a strategic point on the Sanyō Road, along which the daimyō processions had to travel to get to Edo from the west. Ieyasu Tokugawa installed his son-in-law, Terumasa Ikeda, in the region to maintain a close watch over the daimyō of western Japan. Terumasa immediately set about demolishing Hideyoshi’s castle, and spent the next eight years constructing its replacement. Designed to inspire awe and admiration, the new castle, notwithstanding its elegant appearance, was constructed for battle.

Haunted by vengeful spirits, the castle tower begins to tilt

Himeji Castle has a rare layout. It straddles two hills, Himeyama Hill and Sagiyama Hill, giving it prominence and unobstructed views over the otherwise flat land on which it is sited. Three moats were dug to provide additional protection. The inner moat, which is still visible today, encloses the castle itself. A second moat encircled the samurai residences, while the townspeople lived within the third, outer moat. Very few castles were designed to allow townspeople to live within the castle enclosure. Two other examples would be Osaka Castle and Odawara Castle.

Immediately after the completion of the castle, word began to spread that the main keep was leaning to one side. The chief carpenter, apparently distraught at the news, is said to have leapt to his death from the top of the castle. The ground nevertheless continued to subside, and people feared that this was caused by his tormented spirit. This state of affairs continued until modern times, when the subsidence was finally resolved with the major restoration work undertaken from 1956–1964.

The main castle tower sits atop Himeyama Hill, with the Honmaru (main enclosure) and Ninomaru (second enclosure) sections descending from this point like a staircase. The Nishinomaru (western enclosure) section atop Sagiyama Hill was left uncompleted by Terumasa Ikeda, but completed by his successor, who constructed the Nishinomaru Palace residence and the Keshō Yagura watchtower, completing the entire layout.

The main keep of the castle complex has five distinct tiers, which contain six floors and a basement. Three smaller keeps to the east, west and northwest, are connected to the main keep by a system of corridors and watchtowers. The main keep sits atop a fifteen-metre-high stone wall. The building itself measures a further thirty-one metres in height. The entire building is constructed around two massive supporting pillars that extend from the basement to the top floor.

Defense mechanisms disguised as ornamental details

The truly remarkable aspect of Himeji Castle is the way that so many creative methods have been employed in the defense of this vast castle. A wide range of contrivances intended for the defense of the castle itself appear as simple ornamental details. For instance, the decorative gables and lattice windows had a secret space large enough to hide a soldier, and the basement was fully provisioned to withstand a siege, with cooking areas and even toilets in place.

The strategic Sanyō Road, which connected east and west Japan, and along which the daimyō processions had to pass, was routed right through the castle complex. All travellers had to proceed through the massive castle gates. The distance from the Ōtemon Gate into the San-no-Maru section and on to the main keep is less than two kilometres. However, travellers had to pass through a complex series of twists and detours and even dead ends that controlled the flow and pace of traffic, and which meant that gaining access to the castle was not easy. Moreover, the road at each of the ten gates placed on the route turned through a sharp right-angle on each side of the gates, making it easier to attack invaders from the sides. In addition, the route was lined on both sides with seemingly never-ending earthen walls which obstructed the lines of sight. Tiny openings in the walls enabled the defenders to fire at invaders, leaving no chinks in the castle defenses.

An Unparalleled Masterpiece of Timber Design and Construction

What gives Himeji Castle its distinctive shape is the decorative gables and eaves of its many roofs. The way that the differently shaped gables on each level and each side of the tiered roofs have been skillfully arranged is one of the most striking aspects of the exterior appearance of the castle buildings. Variety is added to the appearance of the white-plastered exterior through the use of either curved bell-shaped katōmado windows or rectilinear lattice windows.

With the Meiji Restoration and the fall of the feudal shogunate, Himeji Castle passed into private ownership and the buildings fell into disrepair. In 1882 fire destroyed the buildings of the Bizen-maru, directly below the main keep. Fortunately though, the fire burnt itself out and the main keep remained unharmed. This incident led the townspeople to demand that the castle be properly maintained, and in 1912 it became a municipal park.

In 1931, the castle complex was designated an ‘Old National Treasure’, and major restoration work was begun. This work was halted when Japan entered the Second World War. The city of Himeji was bombed twice, and an incendiary bomb even fell on the castle itself. However, the fire bomb failed to detonate and the castle was once again spared.

In 1951, the castle was again designated as a National Treasure, and restoration work was completed in 1964. Himeji Castle was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1993 as ‘the culmination of Japanese castle architecture in wood, [with] outstanding universal value’. Another major restoration of the entire castle complex was completed in 2015, and the castle was returned to its former gleaming splendour, much to the delight of visitors.

Location:

Himeji City, Hyōgo Prefecture

Website: http://www.city.himeji.lg.jp/guide/castle.html

Access:

A 20-minute walk from JR Himeji Station or Sanyō Himeji Station, or catch the bus from the Shinki Bus Terminal near the north entrance of JR Himeji Station and get off at the ‘Otemon-mae’ bus stop.