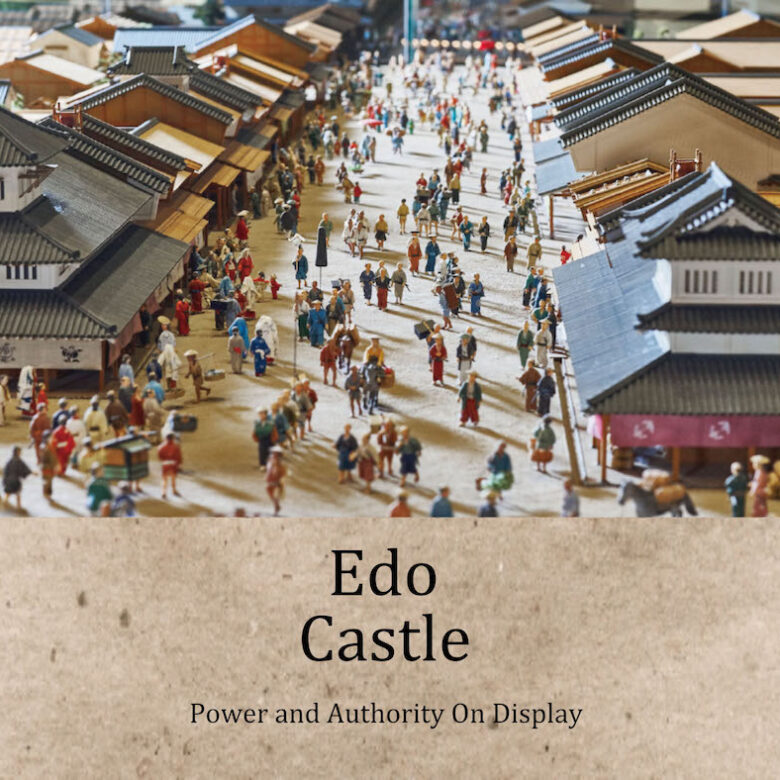

Having unified the warring states of 16th century Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu turned his attention to the construction of a majestic castle on a scale that would fittingly demonstrate the power and authority of the Tokugawa Shogunate. To find out more about this aspect of Tokyo’s history, who better to ask than Edo-Tokyo Museum curator Sugiyama Satoshi. We find out about the tenka bushin system of national civil works that Ieyasu implemented, and events such as disastrous fires and financial setbacks that thwarted Tokugawa ambitions.

Text : Sasaki Takashi / Special Thanks To : 江戸東京博物館・学芸員 杉山哲司 Satoshi Sugiyama / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Ota Dokan / Shogun / Shogunate / Japanese Castles / Tokyo / Tokyo Imperial Palace / Edo / Tokugawa Ieyasu / Edo Castle

16 km Circumference Makes Edo Castle Japan’s Largest

After his triumph at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Tokugawa Ieyasu, now the Commander in Chief of all Japan, began the full-scale upgrade of Edo Castle three years later on the site he chose for his seat of command. The original castle on the site was built by military strategist Ōta Dōkan in 1457, during the Warring States Period. When Ieyasu took over the castle in 1590, it was a comparatively small, shabby structure at the edge of Hibiya Inlet, an area of tidal mud flats connected to Edo Bay.

Part of Ieyasu’s project involved having the castle surrounded on all four sides by a system of waterways with a total circumference of four “ri”, about sixteen kilometres. This included the Sumida River, Tokyo Bay and the outer castle moats. Sugiyama Satoshi, a curator at the Edo-Tokyo Museum, explains the significance of Edo Castle’s vast area.

“Basically, Edo Castle had to be bigger than any other castle ever built. This was as much about consolidating the authority of the shogunate as it was about building an impressive castle. The “tenka bushin” system that Ieyasu implemented to push through his national civil works programme meant that daimyō (feudal lords) from all over the country were forced to gather in Edo and contribute to the construction. This was an important part of clearly demonstrating the power and prestige of the Tokugawa clan to the world.”

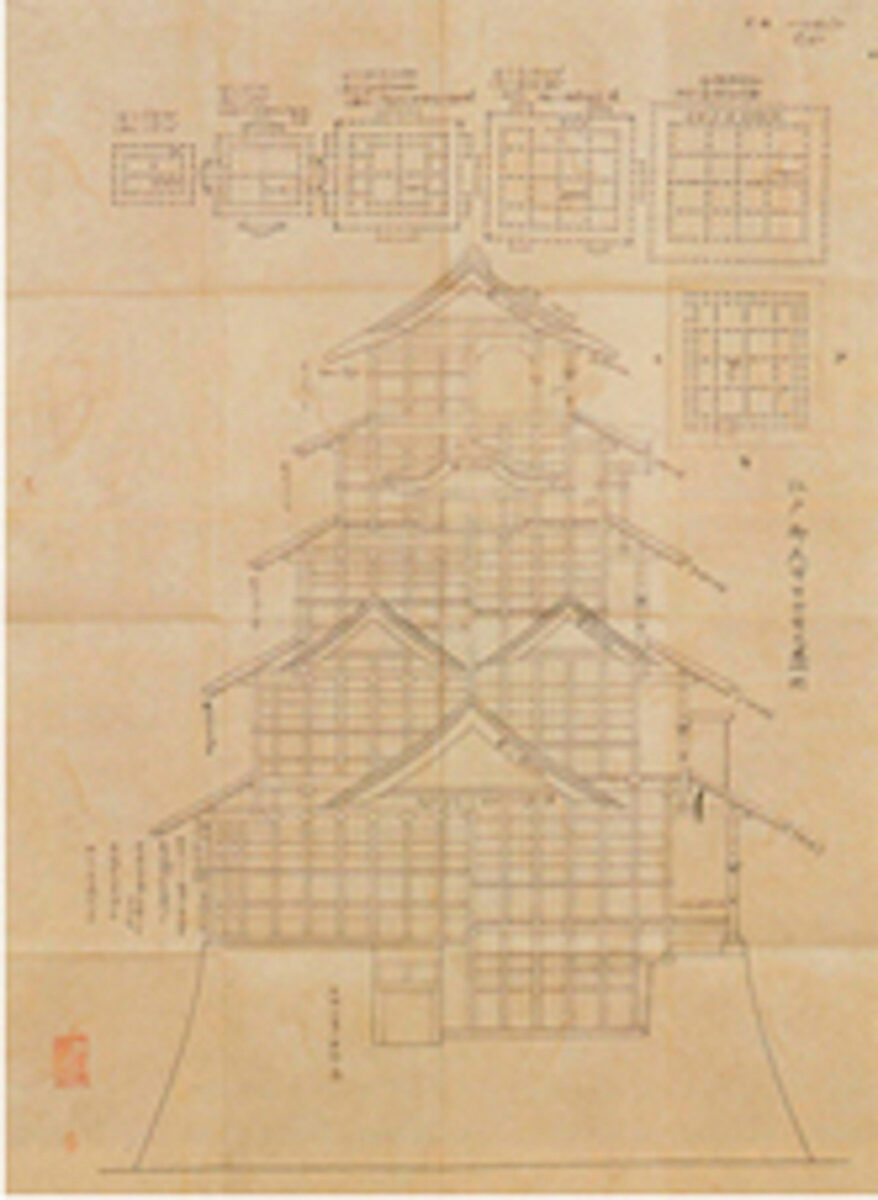

The construction of the tenshu, Ieyasu’s main castle tower, was completed in 1606. However, the tower was rebuilt twice more over the next thirty years, as subsequent shogun’s stamped their own authority on Edo Castle.

“The main tower building of the castle was rebuilt each time the shogun changed, first from Ieyasu to Hidetada (the second shogun), then from Hidetada to Iemitsu (the third shogun), getting larger with each new generation. It seems as if they wanted to show that the shogunate’s power was now even greater than it had been under the previous generation.”

“Known as the Kan’ei Keep, the magnificent castle tower, completed in 1638 during the reign of third shogun Iemitsu, consisted of five tiers with six floors, and reached a height of 59 metres. That would be equivalent in height to a twenty-storey building today.”

Great Fire of Meireki Deals a Devastating Blow

The Great Fire of Meireki struck Edo in 1657, just nineteen years after the completion of Iemitsu’s tower. Most of Edo was burnt to the ground and up to 100,000 lives were lost in the conflagration. Edo Castle did not escape the fire. Almost the entire complex, apart from the Nishi-no-Maru, was destroyed. Iemitsu’s magnificent tower and the extensive palace buildings surrounding it were incinerated.

Many buildings in the Edo Castle complex were reconstructed following the fire, with the exception of the castle keep. Reconstruction of this grandiose tower was opposed by Hoshina Masayuki, half-brother of the previous shogun Iemitsu and counsel to the fourth shogun Ietsuna (who was only sixteen years old at the time).

Rebuilding Edo More Urgent Than Restoring the Castle

Hoshina Masayuki’s argument was that, since the castle keep had never been employed in battle, it really had no purpose other than as a tower from which to get a better view of the city below. Rather than squandering manpower and resources on a vanity project, he counselled that efforts be put into rebuilding the devastated city of Edo. As a result, the reconstruction of the keep was put on hold for the time being.

Plans to reconstruct the castle keep were reprised in 1712 by Arai Hakuseki, an advisor who was working on governmental reforms. However, this project ended before it began, with the death of the seventh shogun Ietsugu and Hakuseki’s loss of power. Subsequent financial difficulties experienced by the shogunate meant that reconstruction plans were not considered again.

The Tokugawa government was content to continue conducting its political affairs from its “castle without a keep” for over 200 years—from the time of the 1657 Meireki fire until the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown in the 1867 Meiji Restoration. Sugiyama san explains that a clue as to why this was so can be found in the changing nature of politics itself during this period.

“As the Tokugawa shogunate became more and more firmly established, emphasis was increasingly placed on ceremonial aspects of politics, rather than on displays of military might. The shogun’s authority was demonstrated in more subtle ways. For instance, when daimyō had an audience with the shogun, there were strict rules around how close they were allowed to get, based on their rank. Low-ranking daimyō would have to sit at such a distance that they would scarcely have been able to glimpse the shogun. This was also a way of emphasising authority, without the need for a towering castle.”

Traces of Edo Castle in the East Gardens of Tokyo’s Imperial Palace

Edo Castle, seat of power for the Tokugawa Shogunate for over 260 years, became the Imperial Palace in 1868, after the shogunate was overthrown. In addition to the residence of Their Majesties the Emperor and Empress, the extensive former castle grounds now also contain palaces used for ceremonial occasions, and the buildings of the Imperial Household Agency.

Many remains of the original Edo Castle can be seen in the East Gardens of the Imperial Palace, which, along with Kōkyo Gaien National Garden and Kitanomaru Garden, are open to the public.

Passing through the same main Ōte-mon gate that the daimyō of the feudal era would have used, one is struck by the magnificent stone walls lining both sides of the approach to the former castle. Particularly impressive is the Honmaru Nishinomon gate (the structure itself has been lost but the stone foundations remain), constructed of enormous hewn stones, each taller than a person, perfectly fitted atop one another without any gaps. Seeing this, one can begin to appreciate the manpower, resources and technical skills that went into the construction of this once-magnificent castle under the tenka bushin civil works system.

At the top of the slope past the Hyakunin-bansho and Ō-bansho guardhouses, one finds oneself in a vast open space. This is the site of the former Honmaru Palace. At the far end of this extensive grassy space stands the tenshu-dai, the base of the former castle tower. The tenshu-dai that we see today was rebuilt the year after the Great Fire of Meireki, by the Maeda clan of the Kaga Domain. The stone base measures 45 metres north to south, 41 metres east to west, and is eleven metres high.

Looking up from the base of this huge stone structure, one can imagine the grandeur of the former Edo Castle tower. From the top of the tenshu-dai, one can look out over the Honmaru Palace site, the woods surrounding the Imperial Palace buildings, and even the glass and steel skyscrapers of Tokyo’s financial district to the east, built on former castle land inside the outer moat (now buried) where feudal lords once had their Edo residences.

There are numerous other attractions within the Imperial Palace East Gardens, including the site of the Ō-oku palace, where the Tokugawa women resided, and the immaculately manicured Ninomaru Garden. Among the trees to the immediate southwest of the Honmaru Palace site, an engraved stone and a signboard mark the location of the former Matsu no Ōrōka grand corridor. A sidewalk now lines the outside of the former inner moat, encircling the Imperial Palace and its extensive grounds. One lap of this popular walking and jogging course is about five kilometres and provides further insight into the size and scale of Edo Castle.

* Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum is currently closed for a major renovation and is scheduled to reopen in 2025. Details here: https://www.edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp/en/