Hokkaidō’s Shiretoko Peninsula, one of Japan’s coldest and most remote natural environments, is a treasure trove bursting with life. Here in Shiretoko, where the mountains thrust straight up out of the sea, it is entirely possible to spy on wild bears after breakfast and still have time to go whale watching before lunch. In recognition of its diverse natural environment, much of the Shiretoko Peninsula was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005, cited as an outstanding example of the interaction of marine and terrestrial ecosystems.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photo : 青柳健二 Kenji Aoyagi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Japan World Heritage / Shiretoko / Hokkaido / Sea Ice

Formed by Volcanoes and Sculpted by the Sea

The Shiretoko Peninsula, a narrow strip of land jutting out into the Sea of Okhotsk at Hokkaidō’s north-easternmost point, was formed as the result of undersea volcanic activity over eight million years ago.

Volcanic activity then began on the peninsula itself half a million years ago, and the peninsula’s two active volcanoes, Rausu-dake (1,661 m) and Iōzan (1,562 m), first erupted around 250,000 years ago. These volcanoes remain active, with the most recent eruption having occurred within living memory.

The peninsula is widest at its base, measuring twenty-five kilometres from the Shari-chō area on the western side to Shibetsu-chō on the eastern side. The land tapers away to a point at Cape Shiretoko, seventy kilometres away. The World Heritage site covers 71,100 hectares, including the land from the central part of the peninsula to Cape Shiretoko at the tip. The surrounding marine area, extending three kilometres from the shore out to the two hundred metre depth mark, is also included in the site.

Eruptions have occurred at Shiretoko’s active volcanoes in recent times. Travel journal illustrations from the late Edo Period (1603 – 1868) show a pall of smoke hanging over Iōzan. When Iōzan erupted in 1880 and 1936, hundreds of thousands of tons of pure molten sulphur poured out of the mountain – an extremely rare type of eruption compared to lava flows. Sulphur mining operations were set up to take advantage of this bounty. Over on Rausu-dake, the lava dome at the top of the mountain is known to have formed when the volcano erupted in the late Kamakura Period (1185 – 1333).

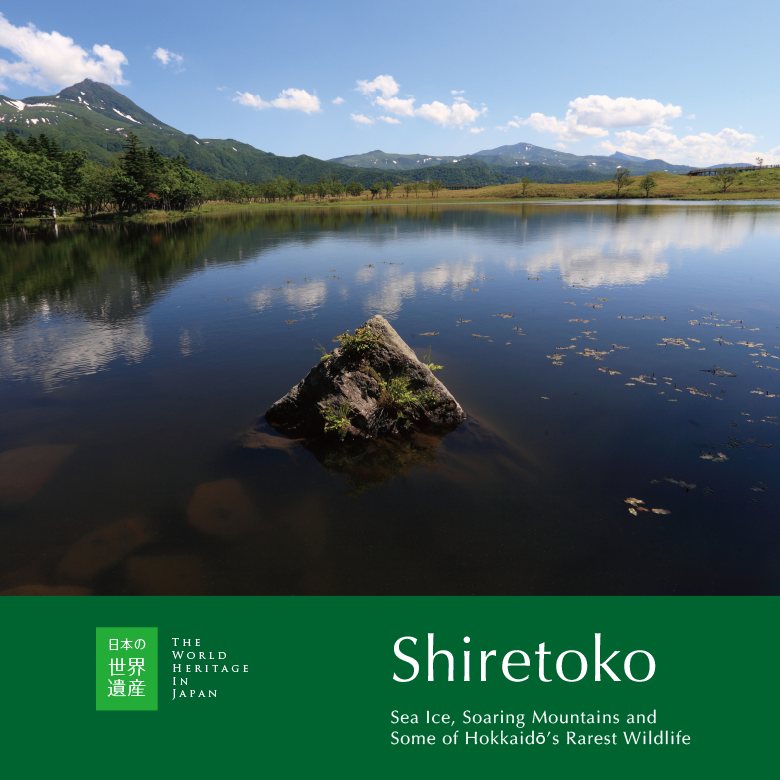

Hundreds of thousands of years ago, lava flowed out of Shiretoko’s erupting volcanoes and into the sea. On the Sea of Okhotsk coast, the tips of the solidified lava flow were eaten away by waves and drift ice bashing against the rock, resulting in sheer cliffs. Not far from the coast, subterranean water channels feed the Shiretoko Five Lakes, while the lava plateau that formed at the base of nearby Rausu-dake is now densely covered in old-growth forest.

Land and Sea Bursting with Life

In late January, ice floes come drifting across the Sea of Okhotsk, completely covering the sea around Shiretoko. Consisting of frozen sea water, this drift ice contains enormous amounts of phytoplankton. In spring, when the ice melts and the upper layers of the sea warm up, this phytoplankton multiplies rapidly, causing a plankton bloom that in turn triggers an explosion in the population of the marine life that feeds on plankton, including the krill that whales love to eat.

The nutrient-rich sea makes the perfect habitat for all manner of creatures. The Steller’s sea eagle arrives on the drift ice, and white-tailed eagles nest here. The peninsula attracts sea lions and seals in winter, with the spotted seal giving birth and raising its young here.