With around six hundred different species of birds inhabiting the islands of Japan from the subarctic north to the subtropical south, this is a bird-watcher’s paradise. Birds of all shapes and sizes have adapted not only to the wide variety of climate divisions, but also to the vastly different types of terrain, from coastal to alpine and everything in between. In this series, wild bird photographer Gōichi Wada introduces the wild birds of Japan, even the occasional small animal.

Text and Photos : 和田 剛一 Goichi Wada / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Kōchi Prefecture / Yairochō / Fairy Pitta / Birds of Japan Series / Birdwatching / Birds

How Did the Fairy Pitta Get its Name?

The fairy pitta, a migratory bird slightly larger than a sparrow, visits Japan, particularly Western Japan, in the summer. In winter it heads to the warmer climates of Southern China and Southeast Asia. Its various traditional Japanese names, including maboroshi no tori(phantom bird) refer to the ephemeral qualities of the fairy pitta, a rare bird that can be found in only a few areas deep in the forest. Not only that, but this bird is mostly silent, calling only for a brief period of time.

Passerine birds like the fairy pitta breed within a defined territory and use their call in order to defend this territory during the breeding season. Many readers will have heard the song of forest birds such as the Japanese bush warbler (uguisu), the blue-and-white flycatcher (ōruri) or the Japanese robin (komadori) out in the forest.

The fairy pitta also nests and raises its young with a defined territory and the male calls to attract a mate. The call is a richly-toned two note “kwee-wee kwee-wee” that can be heard from a fair distance away. However, unlike other birds of the same order, the fairy pitta almost never calls once it has found a mate. The process of finding a mate can take up to a week, but might sometimes take only a few hours.

Usually, the quickest and most certain way of locating a bird is by listening out for its call. The fact that the fairy pitta rarely ever calls makes it tricky to observe. However, if there are several fairy pitta in the same area, these birds do seem to call in order to keep each other in check, which can make finding them a bit easier.

A Multi-coloured Beauty

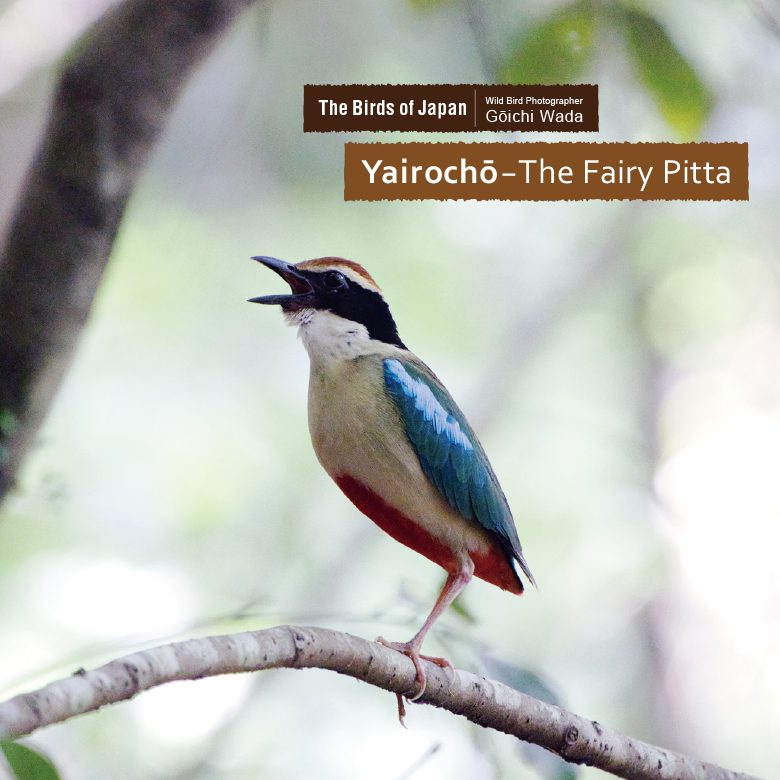

The colourful plumage of the fairy pitta is one of its most distinctive features and, in fact, the Japanese common name, yairochō, means “multi-coloured bird”. These colours include red, black, brown, white, green and cobalt blue.

In Japan the bird’s preferred habitat for nesting and breeding is dense broadleaf evergreen forests but fairy pitta can sometimes be seen in deciduous forests and even in pine or cedar plantation forests. They typically have two house-hunting requirements; one being the gloom afforded by a dense canopy of large trees, and the other being the plentiful availability of the earthworms that they feed their young.

A Dainty Forest Fairy?

The fairy pitta is also known as the “forest sprite” (mori no seirei) or “forest fairy” (mori no yōsei) in Japan. It’s considered to be a mysterious sort of creature because even if you’re lucky enough to catch sight of one in the forest gloom, it’s seldom more than a fleeting glimpse or an elusive flash of brilliant blue.

Clearly the fairy pitta’s elusiveness and brilliant colouring are where it gets its name from, but if you happened to catch sight of this bird during the nesting season, you might have second thoughts about that. As I mentioned, the fairy pitta mainly feeds its chicks on earthworms. Not only is the sight of the adult bird with a beakful of worms fairly grim, so is the sight of the fairy pitta bashing each worm against the ground repeatedly to remove the digestive juices before taking the worms back to the nest. There’s nothing dainty about this fairy!

I was born and raised in Kōchi, Shikoku, an area closely associated with the fairy pitta. Fairy pitta breeding was first documented in the Shimantō River area of Kōchi and there were once many densely populated areas in Kōchi Prefecture. Recently, however, while the number of observations has increased in Western Japan (either due to the increase in the number of observers or to an expansion of habitat), the number of fairy pitta in Kōchi seems to have decreased over the past ten years. I just pray that they continue to breed here and that the chicks return safely each year from their winter journey to the south.