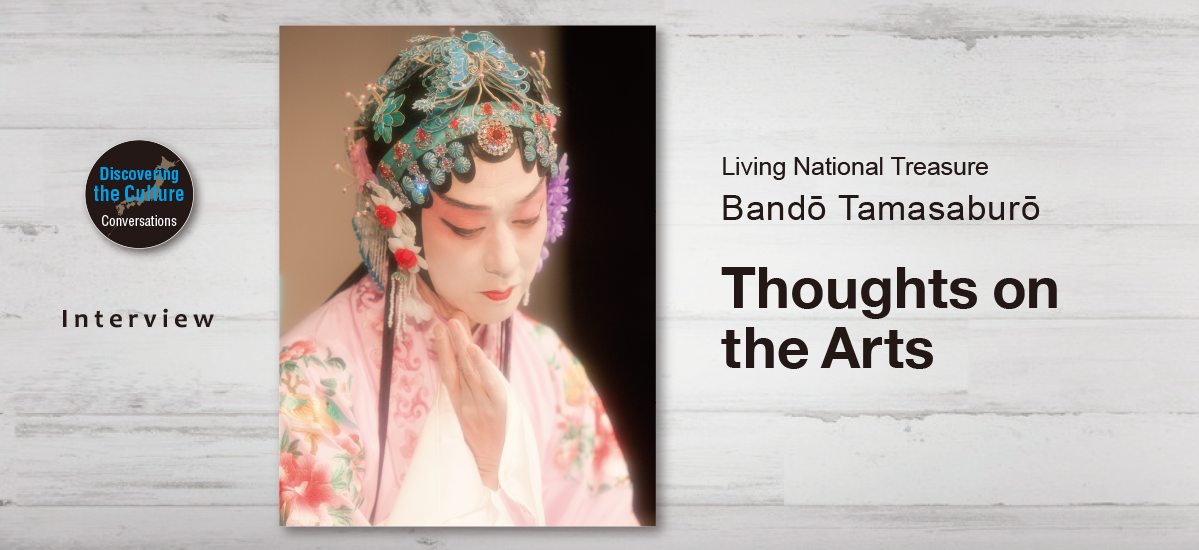

Onnagata, male actors who perform female roles, have been an important aspect of Japan’s kabuki theatre tradition for hundreds of years. Over the course of his long and illustrious career, leading onnagata performer, Bandō Tamasaburō, has held audiences spellbound with his outstanding acting, his beauty, and his convincing depiction of facets of feminine nature.

Actor and director, Kenshow Yamamoto, a former apprentice of Bandō Tamasaburō, talks to the renowned kabuki luminary. Bandō Tamasaburō shares his thoughts on a wide range of topics, from his early childhood to his musings on the theatre, literature, human relationships, and dedication to the Arts.

Below are the translated words of Bandō Tamasaburō, adapted for English-speaking readers.

Text : 山本健翔 Kenshow Yamamoto / Photos : 岡本 隆史 Takashi Okamoto / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Japanese performing arts / Kabuki / Bandō Tamasaburō / Living National Treasure / Shuhari

On Performance

Performance is having sufficient skill to convey the very heart and soul of a character. The skill to communicate this just as smoothly as if one were speaking. This ability stems from the fundamental kata, the basic forms. Once these are completely mastered, the physical expression of an idea comes naturally, unconsciously.

For me, dancing was instinctive. As soon as I could walk, I began moving to music. Somehow I seem to have been moving about with a fan or a tenugui in my hand long before anyone taught me how to dance.

I contracted polio when I was eighteen months old. According to my parents, my favourite part of what I suppose nowadays we’d call rehabilitation therapy, was when the dance teacher would come to the house to work with me. Then, when I was three or four, I started taking dance classes in earnest.

At around the age of six, I became apprenticed to Morita Kan’ya XIV, and made my theatre debut when I was seven. When I was fourteen, I received the stage name, Bandō Tamasaburō V, and was adopted by Morita Kan’ya XIV.

I remember my adoptive father saying, “From now on you’re going to be a professional. The training is going to be very tough – nothing like the lessons you’ve been doing up until now.”

From that point I began training in earnest. The classes I’d been taking for my own enjoyment, I had to start over, practising and practising, to acquire the skills of a professional.

Dance, shamisen, the kabuki instruments, gidayu, tea ceremony, ikebana, piano… Sometimes I even went to two different teachers to learn the same thing. I used to set off at around ten in the morning and finish just in time to get to the National Theatre by quarter past five, when the evening performance began. I carried on like this, I guess, until I was around twenty.

Tragically for me, those six years passed by so quickly! After that I suddenly became really busy, but I still tried to find time to continue at least some of my lessons.

For instance, I used to go to a teacher at the Bunraku-za puppet theatre for gidayu, but also to a teacher of onna-gidayu, where women perform. Actually, lots of well-to-do young gentlemen used to come to the women’s gidayu!

On Literature

We used to have the expression, “machi no shishōsan”, professional teachers of the arts, who could take on apprentices and students. That term is probably obsolete nowadays, though. In those days, young ladies preparing for marriage would take lessons in dance, tea ceremony, flower arranging, that sort of thing, while young gentlemen might learn gidayu or ko-uta(traditional ballads). Some of these young ladies ended up becoming professionals themselves, as did some of the young gentlemen. Ordinary folk became the ones to carry the arts forward. In this way people and the arts were interconnected.

The joy of reciting Japanese is something that seems to be very rare these days. The time when there were professional teachers in the cities was long ago, during the pre-war era of literary culture.

It seems to me that the flow of Japanese literature was interrupted by the Second World War. Now I get a sense of chaos and confusion.

The kabuki playwright, Tsuruya Nanboku IV (1), lived through times of chaos in the late Edo Period. He wrote tales of ghosts, love, and revenge. And while you might not call his works “literature”, they really do seem to resonate with Japanese people. We take comfort in seeing both the good and the evil in humanity. At the root of this is a religious worldview, a kind of moral lesson.

Tsuruya Nanboku’s play, Sakurahime Azuma Bunsho (2), is a tale of crime and retribution in the midst of confusion surrounding good and evil. Even as the audience enjoys the romantic and, at times, macabre storyline, they’re being treated to a moral sermon.

This aspect is present in literature from other cultures, too. Whether it’s Shakespeare, Greek tragedies, or Chekhov. It’s also this aspect that I strive to express in Izumi Kyōka’s work.

I worked on The Idiot with Andrzej Wajda (3), a novel that reflected Poland’s national character; that of a people who had borne the aggressions of several countries. But Wajda believed the work needed to appeal on an emotional level to people of any nationality. So, we sought to honour the essence of Dostoevsky’s work, using drama to find a kind of common language to express that which ordinary words cannot.

I think it’s difficult, at the moment, to have a shared ownership of literature that transcends borders. But I continue to explore various means of doing so, to preserve literature for the future. The Peony Pavilion (4) came about in this way. Although, I never imagined I’d be performing it in Chinese!

(1) Tsuruya Nanboku IV (1755 – 1829) was an Edo Period kabuki and kyogen playwright.

(2) Along with Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan, the play Sakurahime Azuma Bunsho is one of Tsuruya Nanboku IV’s best known works.

(3) Andrzej Wajda (1926 – 2016) was a Polish film director. In 1988 he directed the play, Nastassja Filippovna, an adaptation of the last chapter of Dostoevsky’s novel, The Idiot. Bandō Tamasaburō played the parts of both Prince Mishkin and Nastasja. In 1994, the play was made into a film titled Nastazja, also directed by Wajda and starring Tamasaburō.

(4) The Peony Pavilion is a famous Chinese play written by Tang Xianzu (1550 – 1616). The play is said to be the greatest masterpiece of Chinese opera.

On East-West Differences

The West and Japan are very different. For instance, one mustn’t really stoop or crouch in a Western-style gown, but one may in kimono. In the West, activities are mostly performed standing, occasionally sitting. Likewise, plays are mostly performed standing, with the actors only occasionally seated. In Japan, activities tend to be carried out while sitting on the floor, with people only standing up to move to another spot. Because we live differently, the way we think is also different.

In China people also stand, but their feet remain on the ground. Performers don’t defy gravity as they do in the West. If you look at ballet you’ll know what I mean.

Western theatre is fundamentally existential, although there are some fantasy plays. In a sense, Eastern theatre brings into being things that don’t exist. When a performer muses on something that isn’t real, when the audience joins in that musing, this is where a sense of empathy develops and the unreal becomes real in their imaginations. There’s a sort of “theatrical pleasure” to be discovered here; the pleasure of a shared understanding that has no need of words. This is an important aspect of Eastern theatre.

Reaching this shared understanding is one of the challenges for me when it comes to working with Western plays. In order to accomplish a shared understanding, it’s necessary to understand the Western psyche, Western values and attitudes, ideas about religion. In short, you have to have a window into their soul. If you have this understanding, the precise details of a play become less important. To draw a comparison with the process of literary translation, rather than adhering strictly to the word of the original, the translator needs to understand where the writer is coming from, and needs to be able to express those ideas appropriately in language that resonates with Japanese readers. In order to do that, to find the appropriate cultural references, you have to be even more well-versed in the arts of Japanese language and literature, than in the language of the original.

On Shuhari

Morita Kan’ya, my adoptive father, often used to say that unconventionality is something reserved only for those who have mastered the conventions, or the kata. He’d say that anyone who tries to innovate without having mastered those traditional forms is just someone who hasn’t mastered the basics.

It’s through ongoing training that the kata are completely mastered.

We have the term, shuhari (守破離) that describes how mastery is attained through following the teachings of an expert. First comes shu (守) or “obey”. In this first phase we learn, or obey, the fundamentals. Next, with ha (破) or “tear”, having learnt the kata from our teacher, we are exploring and developing insight into the underlying principles. Ri (離) is “to separate from”. This is when the performer is able to separate, or transcend, creating his own approaches. Yet, no matter how much we separate, or innovate, we don’t abandon those underlying principles. We remain anchored by shu, those fundamentals that we first mastered.

Andrzej Wajda said that the arts follow a repeated cycle of inheritance and development. We inherit from our predecessors and pass on to our successors. When it comes to development, we break with convention, using the past as a springboard towards new ideas and techniques. This, in essence, is the shuhari cycle.

And it’s precisely that initial training that makes this cycle possible. Whether you call it shuhari as we do in Japan, or inheriting and developing as Wajda-san did, there can be nothing to pass on if nothing is developed, and nothing to develop if nothing is passed on.

With theatre, I believe the fundamentals we adhere to are the literature; essentially, the scripts. Without being able to read the scripts, there would be neither acting nor direction. So for me, shu relates to the scripts.

Take buyō for instance. The basis of buyō dance is classical poetry. The question is, how to express the essence of the poem in movement?

These days, with the traditions of literature, poetry and language having been ruptured, there is nothing to adhere to and nothing to break from. So there can be no shu; no ha. All we’re left with is ri, separation. But this is separation without foundation. Performing arts of any real substance these days are few and far between.

At the moment, in terms of following the path of the arts, of passing something on, the future does seem bleak to me. People are more concerned with the end result than with the process of getting there. We live in a world of instant gratification.

I’m not saying there’s necessarily anything wrong with getting things done easily. For instance, we can buy ready-made deli foods without having to be there for the harvesting and cooking. But we’ve separated from our traditions entirely, to the point where money can buy us anything we want. The use of cards instead of cash is becoming widespread. Everything has been reduced to data, endless streams of data, and all we have to do is switch on and switch off, on and off. It’s instant. I don’t see any pathway for the arts here.

On Redeeming the Human Soul

The concept of michi or dō, the tradition of following a prescribed pathway towards mastery of an art, has become increasingly rare. I genuinely do think that we live in grave times.

One thing I can say is that whenever I come across people who are striving for their art, I want to share my knowledge with them to the best of my ability. This, to me, is en (5), which I believe is the most important thing we have.

An example is the Kodō taiko drumming group (6). They shut themselves away from the rest of the world on Sado Island, devoting all their energy to perfecting their art. I’d say what they have is mental fortitude, but it can be really hard. And not just Kodō, but others like them.

What I’m trying to say is that in order to regain the human spirit, people need to seek out and appreciate real-life experiences.

Get out and meet people. And if that’s difficult, go and watch people performing on stage. Even in doing that, there’s a human connection. Especially for people these days whose main source of human interaction is online and anonymous, it’s just so important to get out there and have real experiences, real connections.

(5) En, the Buddhist concept of destiny and human connection.

Bandō Tamasaburō

Bandō Tamasaburō V. Japanese actor. Film and theatre director. A leading kabuki onnagata performer. Maintains the traditional succession of numerous important roles, while breaking new ground in kabuki. Has been invited to perform in major international theatres, collaborating with world-leading artists such as ballet dancer and choreographer, Maurice Béjart; cellist, Yo-yo Ma, and dancer and actor, Mikhail Baryshnikov. As a film and theatre director, he creates worlds of exquisite beauty. In 2012 he was named a Living National Treasure, and in the following year received the French Commander of the Order of Arts and Literature medal for his achievements in arts and culture.

Thoughts on my mentor, Bandō Tamasaburō

Yamamoto Kenshow

To me, the arts are all about mentorship. Becoming accomplished in the arts begins with studying under an expert. For me, that person was Bandō Tamasaburō. I am not a kabuki actor, not even in that league, but I’m convinced that the time I spent studying with Tamasaburō is what led me to where I am now.

When I was training under him, from each and every one of his reactions, his values and aesthetics were drilled into me. This was shu, of course. For the thirty years since that time, I’ve been continually repeating the cycle of shu-ha-ri.

I hadn’t had the opportunity to meet with Tamasaburō for quite some time and I was filled with a kind of thrill that was part nervousness, part excitement. My feelings towards him are not something that I can easily put into words.

Once, at a time when I was feeling discouraged and disheartened, my mentor reminded me of the importance of en. His words gave me such comfort. I didn’t have the opportunity to meet him in person again after that, but I continued to follow him, to go and watch his performances. Because, en, those human encounters that many believe are a kind of destiny, lies not only in our direct encounters with each other, but also in our encounters with people’s work.