April 2019 saw the opening of the Yumoto Koichi Memorial Japan Yokai Museum (Miyoshi Mononoke Museum) in Miyoshi City, which houses an extensive collection of over 5,000 yōkai objects and pieces of art amassed by one of Japan’s best-known yōkai collectors, Yumoto Kōichi. The city of Miyoshi, located in Hiroshima Prefecture, was the setting of a series of hauntings that formed the basis of a well-known ghost story from the Edo Period. The museum provides the means for Yumoto san to preserve and pass on the yōkai collection that he has spent decades putting together. As Yumoto san was preparing for the opening of the new yōkai museum, he spoke to us about his life’s work and why yōkai continue to hold such a strong appeal.

Text : 村田保子 Yasuko Murata / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Yōkai Storyland / Yōkai / Yumoto Koichi / Night Parade of One Hundred Demons / Miyoshi / Yōkai Museum / Miyoshi Mononoke Museum / Hyakki Yagyō

Yumoto Kōichi

Yumoto Kōichi is one of Japan’s foremost yōkai scholars. During the course of his research, he has built up a collection of over 5,000 yōkai objects and pieces of art. Former curatorial director of the Kawasaki City Museum, Yumoto Sensei lectures at universities on topics related to yōkai, and engages in the supervision of special exhibitions. He has authored numerous books on yōkai. These include the richly illustrated bilingual (Japanese and English) Yokai Museum: The Art of Japanese Supernatural Beings from the YUMOTO Koichi Collection; Yokai Wonderland – More from the YUMOTO Koichi Collection: Supernatural Beings in Japanese Art, and Yokai Storyland: Illustrated Books from the YUMOTO Koichi Collection (all published by PIE International), as well as many books in Japanese.

The Collection Reveals the Extent of Yōkai Culture

I imagine that many people might think of yōkai as being frightening or creepy, but there are actually a lot of yōkai that are unique, cute and even entertaining. It was that element of surprise that first attracted me. While I was researching and collecting documents related to yōkai , I realised how extensive yōkai culture in Japan really is. Previous research had based its case mainly on evidence from verified sources such as emaki (picture scrolls) and woodblock prints, but this didn’t reflect the true extent of yōkai culture. As well as doing research, I felt that it was extremely important to begin unearthing and gathering up items related to yōkai, so that’s how my collection got started.

Printing Advances Bring Yōkai into People’s Lives

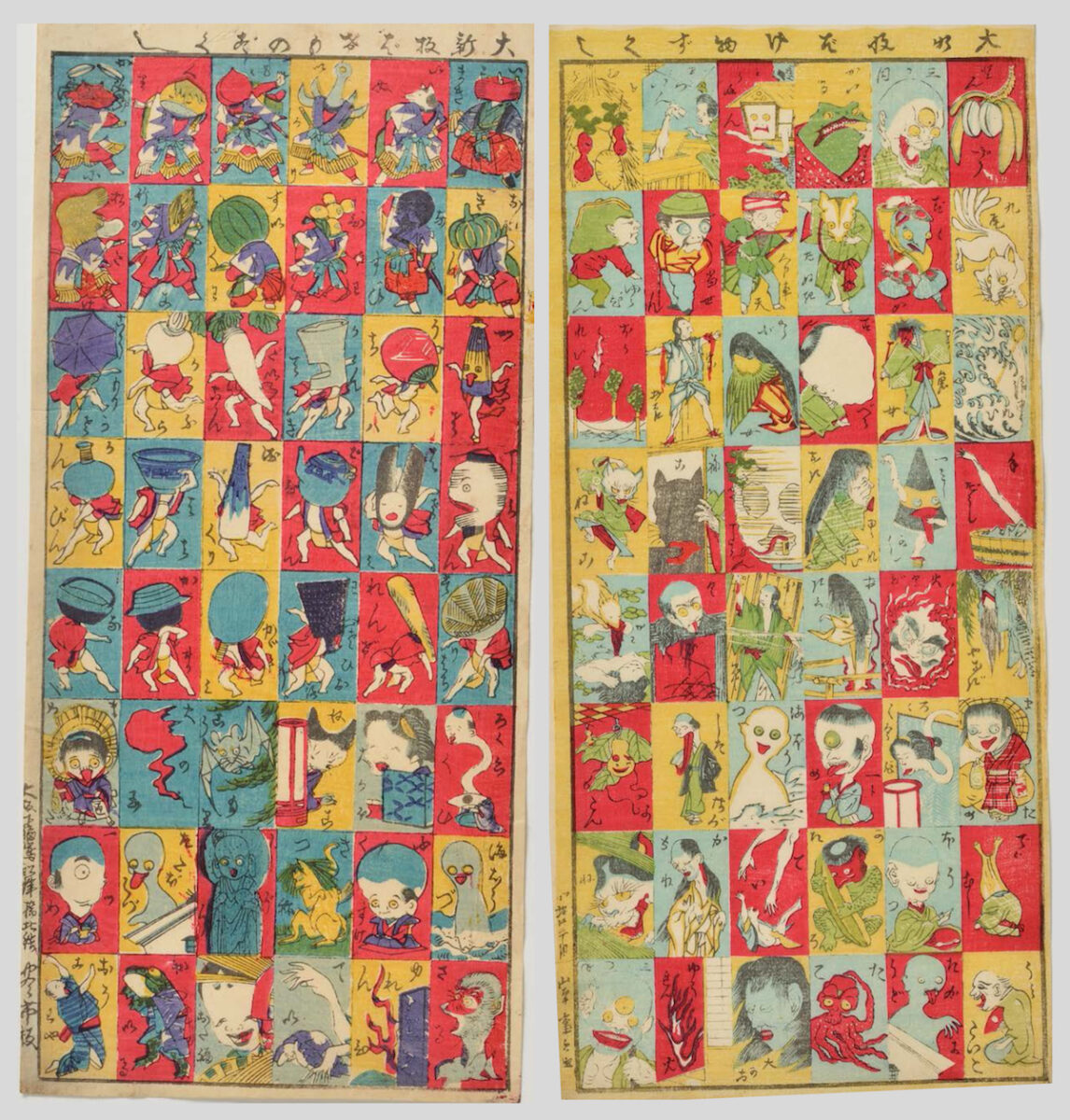

Historically speaking, it was during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) that yōkai came to be depicted as being not only frightening, but also cute. yōkai had previously appeared only in emaki scrolls, but in the Edo Period they became an accepted part of daily life, featuring as patterns on kimono or as netsuke, and even on children’s sugoroku board games and playing-cards. Collecting such things enabled me to see the bigger picture of Japan’s yōkai culture; the way that yōkai had gone from being something frightening to becoming something familiar. After all, if people had considered them frightening, yōkai wouldn’t have been used on clothing or board games – nobody would have wanted anything to do with them. But that wasn’t the case. They were completely accepted by the people of the Edo Period as companions or friends.

It was the spread of woodblock printing in the Edo Period that enabled yōkai to become such familiar characters. Previously, paintings of yōkai had existed as single, one-off pieces, each one painted by hand and prohibitively expensive. Ordinary folk wouldn’t have been able to afford them. But the widespread use of woodblock printing meant that all kinds of pictures and printed stories could be enjoyed by anyone. Yōkai benefited from this move towards mass printing, with stories and picture scrolls becoming widely circulated. I believe that this move released yōkai from the curse of the old mind-set that they were to be feared.

The Modern Yōkai Boom – A Continuation of an Old Tradition

Although yōkai became a familiar part of life in the Edo Period, that doesn’t mean that people suddenly stopped being scared of them. That familiarity is just one aspect of the yōkai story, but it’s not like a game of Othello, where you can turn all the black pieces into white. It was more complex than that. Even as yōkai were becoming more familiar, they still retained, in parallel if you like, the ability to inspire fear.

One way that adults during the Edo Period liked to get a thrill was the Hyaku Monogatari Kaidankai. This was a kind of parlour game where they’d light candles, and guests would take turns telling ghost stories, blowing out one of the candles after each story. When the final candle was blown out, some sort of frightening supernatural occurrence was supposed to take place. Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, children were playing yōkai board games. We may not be conscious of it, but this contradictory approach to yōkai, horrifying on the one hand but cute on the other, continues to this day. For example, while we shudder at the tales of the supernatural we see on television in those ubiquitous summer ghost specials, we don’t think twice about having yōkai smartphone accessories.

This is a continuation of that same multi-faceted yōkai culture that existed in the Edo Period. It didn’t suddenly stop one day. Anyone who’s grown up in Japan knows exactly what a kappa looks like, but I don’t imagine this is something that’s explicitly taught at school or in the home. It’s as if this knowledge is somehow naturally absorbed along the way. Without us being aware of it, yōkai culture, in all its various aspects, has been with us all along.

This tradition has provided fertile ground for the works of pioneers of the modern-day yōkai boom, such as manga artist Mizuki Shigeru or mystery writer Kyōgoku Natsuhiko, to achieve their success. Similarly, the children’s yōkai boom, as seen in popular anime like Yōkai Watch, is likely part of that phenomenon. Works such as these are the product of our own time, so it’s hard for us to look upon them objectively. But in a few hundred years they’ll be looked at through a more objective lens and I believe they’ll find their place within the stream of yōkai culture.

A Comprehensive and Diverse Collection Preserved for Posterity

The oldest picture scroll featuring yōkai is said to be the Hyakki Yagyō (Night Parade of One Hundred Demons), painted in the Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573). This scroll had a big influence on subsequent yōkai culture, with other artists continuing to paint these same yōkai long afterward. You could call this a starting point for yōkai research, but when we say that this is the oldest source, we’re actually referring to two things. Firstly, that this is the oldest source still in existence (that we know of) and secondly, that it’s the oldest work that features only yōkai. Stories about yōkai, such as the Tsuchigumo Sōshi scroll or the Shuten-dōji Emaki scroll, did exist prior to the Hyakki Yagyō scroll, but these were really about how Minamoto no Raikō (Minamoto no Yorimitsu) slayed these demons. These examples were written to highlight the bravery and heroism of Minamoto no Raikō, so they’re not really about the yōkai as such.

At the museum (the Yumoto Kōichi Memorial Japan Yōkai Museum), exhibitions will be organised thematically, displaying yōkai materials and objects of various types, ranging from old scrolls like the Hyakki Yagyō, to kimono, netsuke and children’s games.

Putting on displays for people’s enjoyment is an important part of the museum’s role, but these visual representations of yōkai are only a tiny part of the yōkai world. Each one of these stories began as an individual’s response to an uncanny encounter, which then became hearsay and gossip before becoming part of a greater oral tradition. The visual representation of yōkai came much later, when this oral tradition inspired the creation of the emaki picture scrolls that we have today. Behind each emaki are hundreds of individual stories that are lost to us, meaning that the world of yōkai must be very profound indeed. This world is what we hope to give people a glimpse of. We plan to hold special exhibitions four times a year that look at various aspects of yōkai, opening a window onto this rich and fascinating world.

It’s taken more than thirty years to put this collection together, finding pieces in rare bookshops and antique stores, through art dealers and through relationships I’ve formed with various people. As my activities became known, more and more people came forward with information and items, and the collection expanded. By donating the collection to the city of Miyoshi and having it housed in a museum, I hope to preserve it for posterity. I feel that I’ve been tasked by future generations with taking good care of these materials, so I have to look after them and hand them back to the future in good condition.

Holding exhibitions for the purpose of education and enjoyment is obviously a part of that, but the role of the museum is also conservation and restoration, as well as compiling a database and enabling further investigation and research. This is my vision for the Yumoto Kōichi Memorial Japan Yōkai Museum (Miyoshi Mononoke Museum).