Dr Sheila Cliffe, a Japan-based renowned authority on kimono, bridges the two worlds of fashion and academia with an unparalleled passion for Japan’s national garment. Cliffe firmly believes that kimono, far from being a relic of the past, is a living and ever-evolving art form and fashion statement. In fact, this idea was central to her doctoral dissertation. Over the course of an afternoon at her Tokyo home, Cliffe highlighted the contributions of contemporary designers who infuse kimono fashion with new materials, modern influences, and innovative techniques – in vibrant contrast to the popular notion of kimono as a static traditional garment best seen in museums.

Text : Judy Evans / photo : 小野里保徳 Yasunori Onozato

Keyword : Kimono / Sheila Cliffe

Kimono researcher Dr Sheila Cliffe first came to Japan with the intention of spending the summer learning karate, which she hoped would be useful for the career in acting that she aspired to. However, Cliffe soon came under the spell of kimono; a fascination that would lead her to become Japan’s first non-Japanese kitsuke (kimono dressing) teacher, to an academic career researching and teaching about kimono, to a career as an author of popular books about kimono, and to an unexpected career as a social media “kimono influencer”. The initial one month stay to learn karate grew into a decades-long commitment to Japan, the place that Cliffe considers to be her home.

The Creative Possibilities of Kimono

While kimono is certainly a reminder of Japan’s rich cultural heritage and stands as a beautiful alternative in a world dominated by fast fashion trends, it’s the creative possibilities offered by kimono’s endless variety of colour and pattern that appeal to Cliffe. She’s deeply concerned about what she sees as Japan’s modern obsession with plain, sombre fabrics. “Japan is dull compared to everywhere. Japan likes sad beige. And patterns are disappearing; everything is plain. You can see this in the success of brands like Muji and Uniqlo. This makes it very difficult to for people in Japan to express themselves here with off-the-shelf Western clothes.” This process, this erasure of colour and pattern, began, Cliffe argues, with Japan’s drive to modernise in the late 1800s; a drive that led Japanese men in particular, following the lead of public officials, to turn their backs on the perceived frivolity and femininity of cotton, linen and silk kimono, embracing instead starched shirts and stiff woolen suits in anonymous blacks and browns.

Cliffe herself embodies a time in Japan when people weren’t afraid of vibrancy. She regularly appears on TV and in magazines, or is photographed out and about, in her trademark exuberant style of kimono paired with Western accessories such as hats and jewellery. Each outfit is vividly matched to suit the occasion and her mood. However, contrary to popular perception, Cliffe doesn’t wear kimono all the time. “People think I lead this super glamourous life, but actually I don’t. Gardening or sewing are things I love, and I definitely don’t wear kimono when I’m working in the garden!” Cliffe does, however, wear kimono much of the time and when we meet, she has just arrived home from her sewing class dressed in an understated blue-striped linen kimono – quite a contrast to the flamboyant styles we associate with “Sheila Kimono Style”, the title of the 2018 book showcasing her unique approach to kimono fashion.

Breathing New Life into Old Kimono

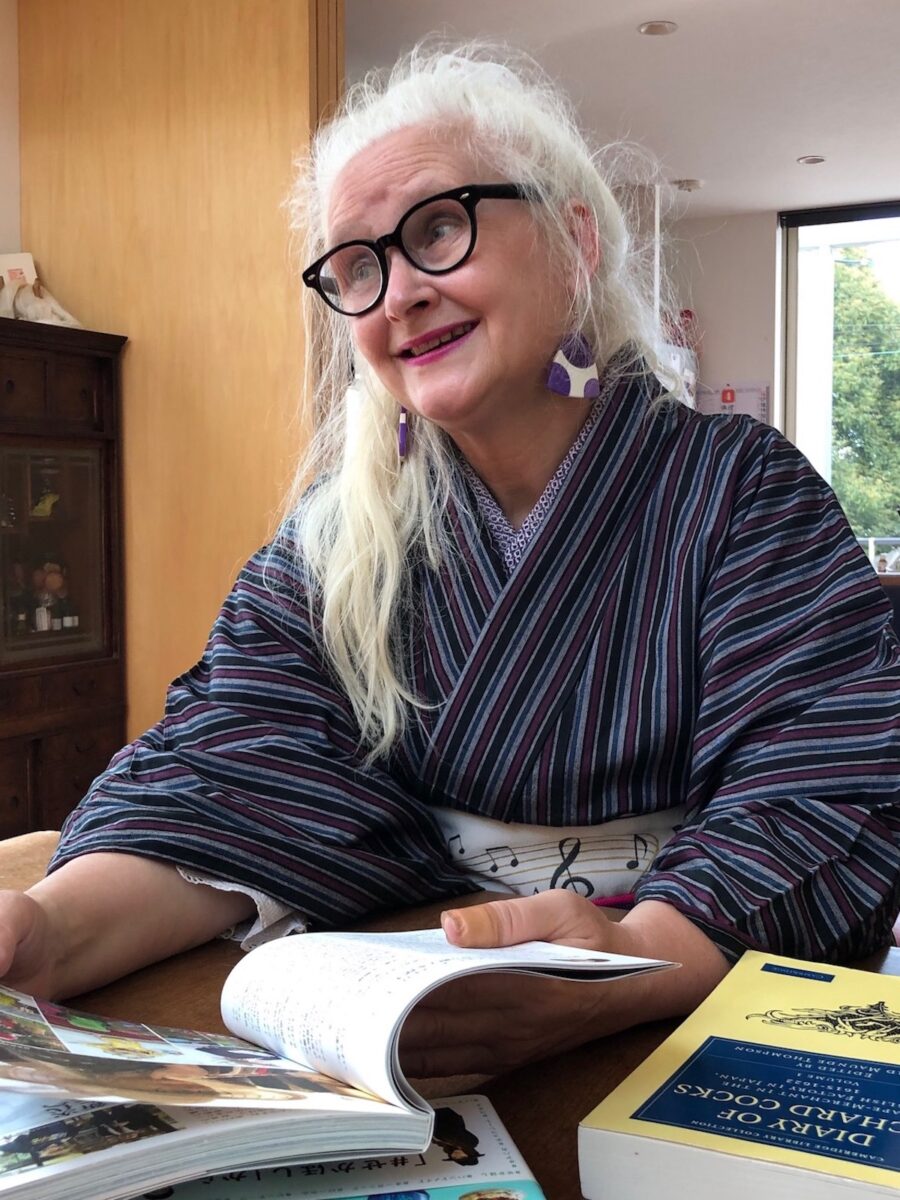

On the topic of sewing, Sheila has attended a popular kimono sewing class for some years now, and was in the process sewing herself a kimono from a bolt of reproduction meisen cloth when we spoke. Meisen is a machine-woven silk that gained popularity around a century ago, and features bold geometric shapes and abstract motifs inspired by the Western modernist art movement. The piece Cliffe is working with features a penguin design. As wacky as penguin-patterned kimono cloth may sound, the modern reproduction in green and brown hues is muted compared to the original. “This design was around in the Taisho Period. There’s an antique piece of this fabric in the Meisen-kan in Chichibu, but it’s in really wild colours – pink and yellow and turquoise.”

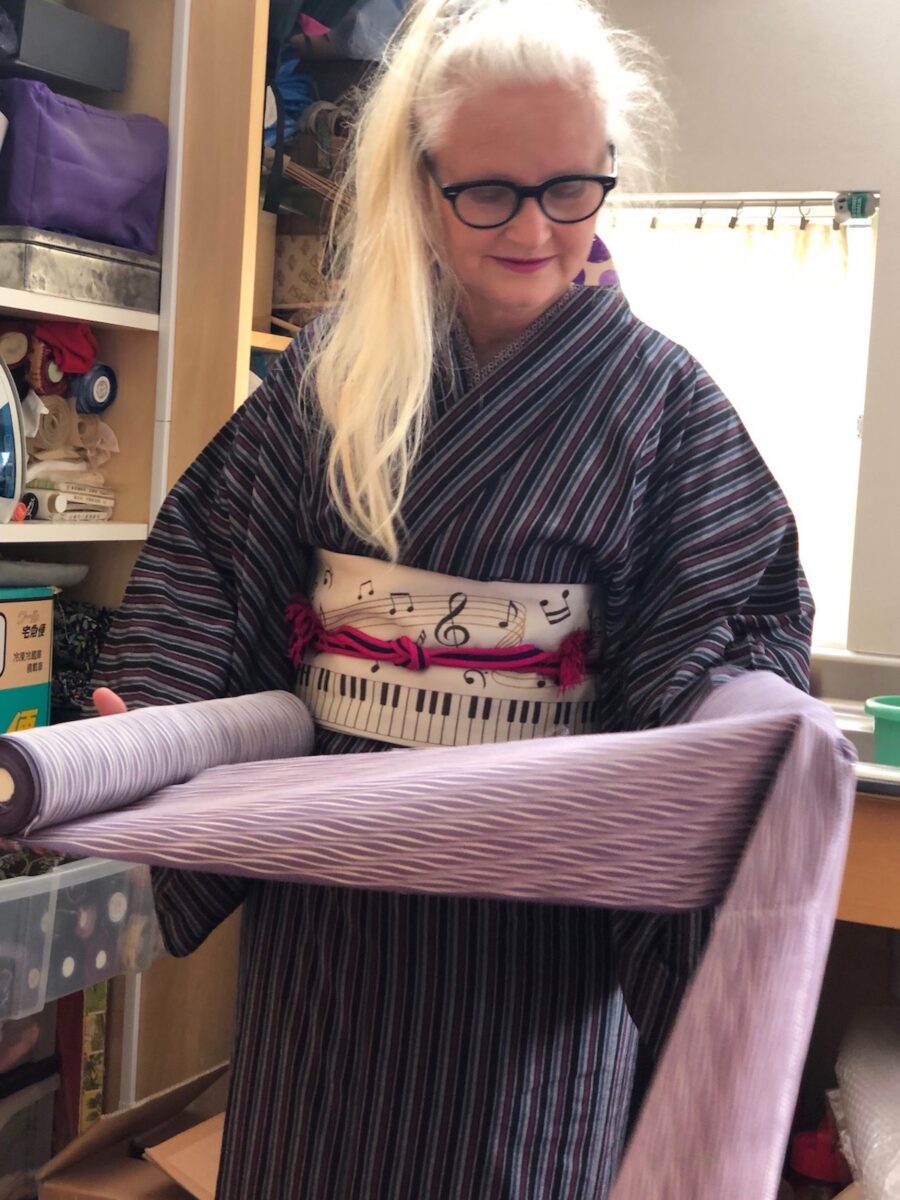

Cliffe’s cupboards are brimming with bolts of kimono fabric from old kimono that she has painstakingly unpicked. After each kimono is deconstructed, the individual pieces are reassembled into the shape of the original bolt of fabric that they were cut from and sewn back together, much like putting a jigsaw puzzle back together. This is so that the fabric can be washed and stretched back out. “A kimono is very modular. You cut all of the pieces out of a twelve-metre bolt of cloth. You can take a kimono apart at the seams and piece the original bolt of cloth back together perfectly. There’s no waste at all. There are no offcuts. It’s all there.”

Next, the bolt of kimono fabric is sent out for “araihari”, a specialist process where the fabric is professionally washed and stretched back to its original shape. This is a vital process to preserve the shape and colour of silk fabric, particularly chirimen, a type of silk crepe woven from tightly twisted silk yarn, that can shrivel to less than half its size when placed in water.

As well as the bolts of fabric that Cliffe has ready to be sewn back into kimono, she has plenty more kimono that she wants to unpick and remake – “enough to last me quite a few years”. She doesn’t buy new kimono, sourcing used kimono instead from antique markets and second-hand shops. And this is where the sewing lessons come into the picture. “If you pay for someone to sew it up for you, it costs between 20,000 yen and 40,000 yen, depending on whether you’re having it lined and how much fabric there is, but you can do that yourself as well. And if you multiply that amount by this number of bolts, that’s a lot of money that can be saved. So, this is what I spend a lot of my time doing.” It’s labour-intensive but satisfying work.

How to Wear Kimono Appropriately

Does Cliffe’s penchant for mixing Western accessories with kimono mean that she’s a bit of a rule-breaker? “I don’t see myself too much as a rule breaker. The important thing is to separate between the formal and the informal. If you’re going to a wedding or some formal event, it’s appropriate that you wear formal wear and wear it fairly formally. Wearing informal kimono to a formal event would be like going to a wedding in jeans, it just isn’t appropriate.” The issue as Cliffe sees it is that nowadays, in the eyes of many, kimono is strictly reserved for formal occasions, so is only ever worn formally. However, there’s a growing movement of people, particularly young people, wearing kimono casually and wearing it for fun. “I call it redemocratization when people start to wear it again just because they like it, because they want to. Not just because they have to, or just because somebody is getting married.”

Where’s the line between “playing dress-ups” and wearing kimono in a way that’s culturally appropriate? Cliffe believes it’s important to know the basic rules, “but I also think it’s important not to be hung up on the rules. People think it’s some very mysterious, complex thing, and actually, it doesn’t have to be – there’s loads of information online now.” Cliffe suggests taking a look at ayaayaskimono on Instagram for inspiration, as well as for some innovative ways to tie obi. She also recommends beginning with yukata (informal summer kimono often worn at festivals), and even wearing kimono over Western clothes first, “on top of jeans or leggings, with a collar or a turtle neck. Because then you don’t have to worry about the kimono collar underneath, which is a little bit difficult.”

The Evolution of Kimono Today

For kimono to remain relevant, and not just museum pieces whose evolution is frozen in time, it’s important that designers and wearers continue to experiment and innovate and that the story of this evolution continues to be told. Museums hold the power to educate and engage the public, both domestically and internationally, in the rich heritage of kimono. “The museums in Japan will try to tell you that kimono’s story stops with meisen, but meisen is not the end of the story and so that is really frustrating for me. It’s like they’re saying, after meisen we wear Western dress and that’s the end of it.” Sheila’s frustration stems from the the missed opportunities to convey the full story of kimono’s evolution, as well as that of the contemporary designers and craftsmen currently pushing the boundaries of kimono fashion. In neglecting to tell this story, she says, museums fail to showcase kimono’s relevance in modern society, inadvertently perpetuating the notion that kimono is a relic of the past. This is in stark contrast to the story told at Victoria & Albert Museum’s “Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk” exhibition held in London in 2020, and then at Zurich’sMuseum Rietberg from September 2023 until January 2024. “The V&A didn’t stop in 1920 with meisen. They included that whole century between then and now – how people wear it now, how it’s been shown in films, how it’s influenced popular culture, such as the Star Wars costumes, which were very strongly influenced by kimono. And they featured famous contemporary crafts people from around Japan.”

Kimono Style for Men

Cliffe is excited by the innovation happening in the men’s kimono market and speaks enthusiastically about the potential for this aspect of men’s fashion. “Men don’t want to be confined to always wearing muted colours like navy blue, black and brown and things are starting to change. They’re getting more colourful. People like Rumi Rock are designing for men. Also that whole group of designers I introduced to the Victoria and Albert exhibition. Robe Japonica in Harajuku specialises in men’s kimono, and it’s very bright and colourful – they’re even making these perspex geta [sandals] and they’re so gorgeous!” The geta Cliffe shows us combine new materials with traditional craftsman’s skills. “The Kyoto company, Wagizen-Shizukuya, is experimenting with a lot of different materials, even leather – some with a metallic finish. It’s kind of a “Star Wars” look, experimenting with different kinds of hakama, different kinds of coats and cloaks, and bags. They’re masculine; masculine colours, but all kinds of fabrics and textures – hairy-looking fabric with bits hanging off them, even lace!” In his store in the upmarket Ginza 6 shopping centre, Jotaro Saito has kimono for both men and women, with signature lines in denim and jersey knit. “He has some really interesting designs, like sanma, the fish, and jellyfish. So yes, I feel that there’s a lot of potential for men’s kimono. Men want to be stylish too. You can’t hide in a kimono, it attracts attention!”

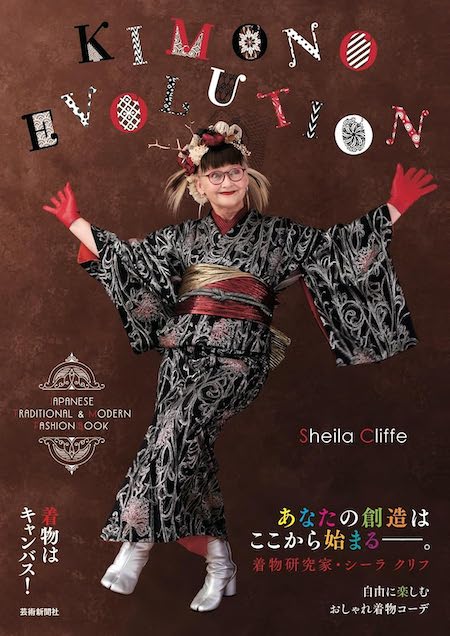

Cliffe continues to challenge prevailing attitudes in Japan and seeks recognition for kimono as an evolving art form; one that bridges the past and present. Her latest book, “Kimono Evolution” invites young Japanese readers to take an active part in the evolution of kimono by using kimono as the canvas for their imaginations.

“Kimono Evolution”, published by Tankobon (in Japanese).

Publisher:GeijutsuShinbunsha Co., Ltd.

https://www.gei-shin.co.jp