Inden-ya, Kōfu City, Yamanashi Prefecture

Text : 塩野米松 Yonematsu Shiono / Photos : 菅原孝司 Koji Sugawara / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Kōfu City / Yamanashi Prefecture / Handcrafts / Artisans / Traditional Skills / Leatherwork / Deerskin / Inden

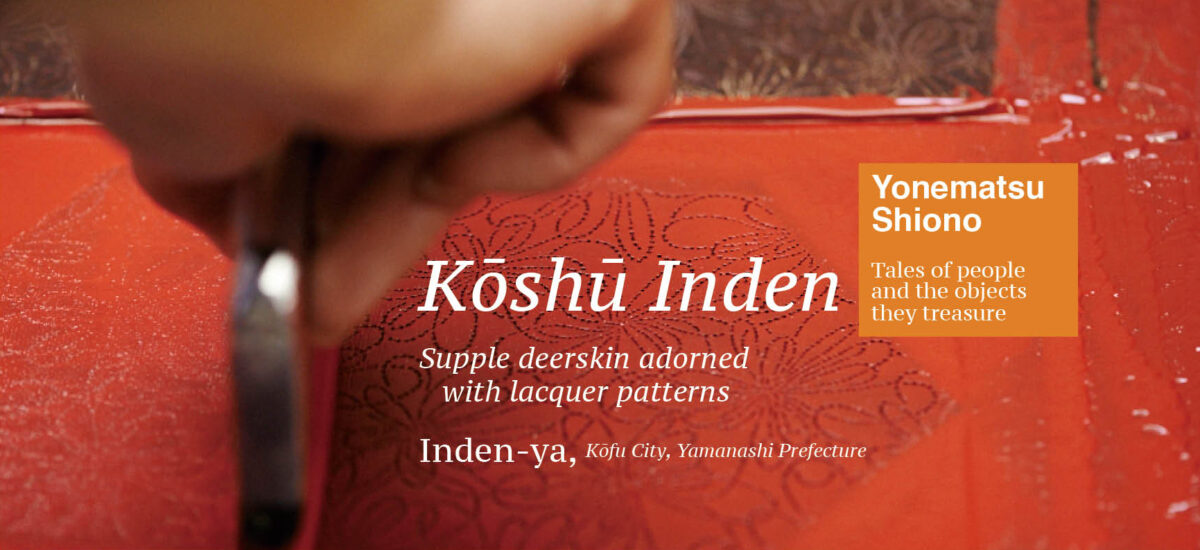

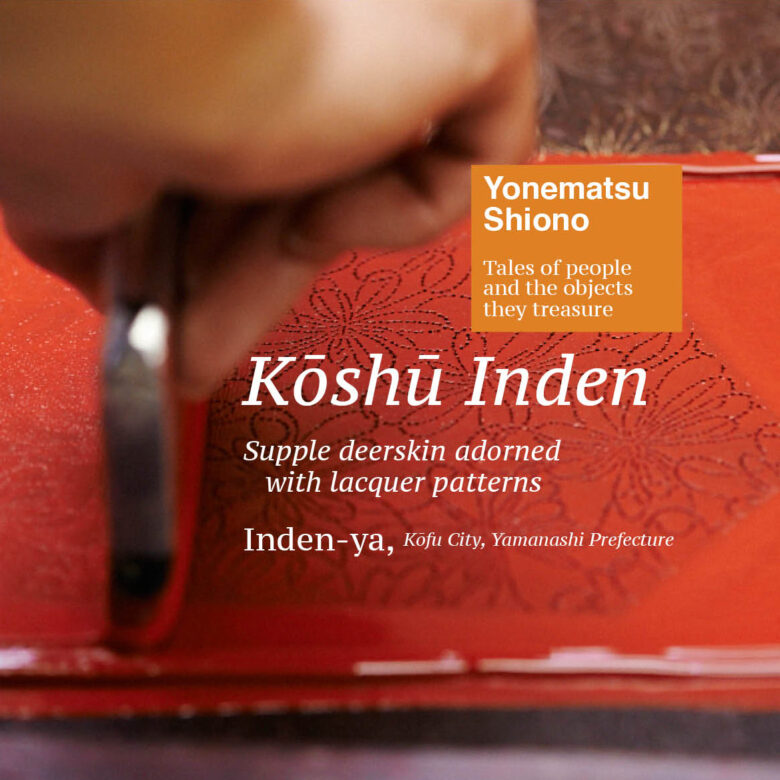

Supple deerskin adorned with lacquer patterns – a secret technique

Inden is the name given to deerskin items decorated with lacquer. The term, inden, is a relatively recent one, believed to have been coined in the early 1600s, when a gift of printed leather from India was presented to the shogunate. However, examples in the collections in the Shōsōin Repository and Tōdaiji Temple, both in Nara, dating back over a thousand years, indicate that techniques used to create supple, durable and beautiful decorated deerskin have been around for a long time indeed. The Shōsōin collection includes tabi socks, while Tōdaiji has deerskin-bound cases for holding correspondence. The inden technique has long been used to decorate harnesses and saddlery for horses, as well as armour and helmets, most likely in all parts of Japan. By the Edo Period (1603 – 1868), the technique was being used to produce stylish accessories such as drawstring tote bags and tobacco pouches.

As the times and fashions changed, these once treasured items gradually went out of style and began to disappear. However, in Kōshū, a city in central Japan that achieved renown for the production of inden goods more than four hundred years ago, the tradition is still maintained and has come to be known as Kōshū Inden.

Not far from Kōshū, in neighbouring Kōfu City, foremost among inden artisans is the venerable ‘Inden-ya’ workshop which has continued the tradition for thirteen successive generations. Each successive head of the household, right up to the present, has not only inherited knowledge of the inden technique, but has also adopted the name, ‘Uehara Yūshichi’.

Secret techniques made public to safeguard the future of inden

Formerly, knowledge of the inden technique was only ever transmitted orally. However, both the knowledge of the technique and the wonderful objects themselves have, over time, been gradually erased. The current head of Inden-ya, thirteenth generation Uehara Yūshichi, concerned that the traditional secrecy surrounding the technique was a threat to its survival, decided to make the knowledge public. This daring move was made in the belief that the more people who knew about inden, the more assured its survival as a technique would be.

Besides which, guarding the technique from competition no longer has the same relevance as it did in the past. There is no longer much danger of imitation. The skill continues to be passed from experts to apprentices, who spend many years honing their expertise. What’s more, the materials and equipment are not easy to come by, and neither is the ability, developed over many years, to discern the extremely subtle differences that make up pieces of the finest quality.

An important aspect of the technique that can never truly be captured or recorded is the knowledge that resides within the hands and the bodies of the craftsmen themselves. Inden is a technique that works to a human rhythm. The trained body moves intuitively and responsively and the finest pieces only ever come to life in the hands of the most experienced artisans.

Ultimately though, it is the customer who will determine whether or not inden has a viable future.

Each Step of the Process the Product of Years of Experience

There are two main techniques employed in the production of Kōshū Inden.

The first is kusube (smouldering), a technique that uses smoke to colour the deerskin and bring out the patterns that have been applied to it. The second is using stencils to apply patterns to the deerskin with lacquer.

Smoke from smouldering straw tickles your nose when you step into the space where kusube takes place. White smoke billows from a kiln that looks for all the world like an old-fashioned Japanese earthen cooking stove.

The kiln has been filled with rice straw, and how well the smoke forms depends on the way in which the straw has been stacked inside the kiln. Too much air space within the stack, and the straw will catch on fire and burn up. The whole point of kusube is to produce smoke, as opposed to heat, so the straw needs to smoulder, not burn. This kiln has been designed for precisely that purpose.

A cylindrical frame called the taiko rotates above the kiln. Pieces of deerskin are stretched around the taiko, attached with fine nails.

The artisan responsible for maintaining the quality of the smoke and rotating the taiko frame is known as the kusube no tantō.

The kusube no tantō has to build his own kiln. Experience is required to be able to build a kiln that will produce continuous plumes of smoke. There is an ideal form for the kiln, but this cannot be replicated according to any formula. Learning the technique involves a process of trial and error and constant back and forth between the new kiln and the kiln of the predecessor, trying to work out where the differences lie and why the new one may not work as well as the old one. An added complication is that all the valuable deerskin being worked with is destined to fill important orders, so despite any misgivings he may have, there is no choice other than to get it right!

Kusube is the most ancient aspect of the inden technique. As the deerskin absorbs the smoke, it gradually takes on a brown colour. A pattern emerges as the colour deepens. This is due to paste or threads that were applied to the deerskin before smoking to prevent colouration of some portions of the leather, much like the dye resist technique. Once the kusabe process is complete and the paste is peeled off, patterns, lettering, or company logos stand out clearly in white against the now brown background.

This traditional technique showcases the special properties of deerskin, which does not require the processing needed for pigskin, sheepskin or cowhide. Once removed from the taiko frame, the deerskin is soft, supple and does not crease.

Nurturing People – the Secret Behind the Tradition

The secret behind Kōshū Inden’s continued success might be in the way they nurture people and make best use of their skills. It is people, after all, who have inherited these skills and passed them down through the generations.

Through the support of other traditional craftspeople, Kōshū Inden’s continuity has been possible. The stencils used are Ise Katagami, which itself is designated one of the Important Intangible Cultural Properties of Japan. Layers of washi (handmade Japanese paper) are bonded together with persimmon tannin and designs carved out using traditional blades, chisels and punches, to create katagami stencils. As many as a hundred and eighty different stencil designs are used.

The Uehara family has its own distinctive way of creating patterns on the coloured deerskin. In addition to stencilled designs in a single colour, multi-coloured sarasa patterns are created by layering several stencils, each in a different colour.

All the craftsmen perform their work in silence.

Kōshū Inden’s artisans must be sensitive to atmospheric changes. The lacquer used to create the patterns is a living thing and its consistency varies, depending on factors such as air temperature and humidity. The artisans have to be able to make constant subtle adjustments when printing with this natural pigment.

Once the kusube and stencilling are done, the deerskin is sewn and the finished products are complete. From here they go to high-end retail stores in Tōkyō, Ōsaka and Nagoya, or to Inden-ya’s flagship store in Kōfu City.

Inden-ya Uehara Yūshichi Co. Ltd.

(Museum and Flagship Store)

Address: 3-11-15 Chuo, Kōfu City, Yamanashi Prefecture 400-0811

Phone: 201 055-220-1660

Website: http://www.inden-ya.co.jp/