Yakushima Island, in the warm seas south of the Japanese mainland, is a rich microcosm of Japan’s remarkably varied flora. Regions of both subtropical and subarctic forest can be seen on the same mountainside, their boundaries clearly delineated according to the elevation at which they sit. Recognised as a valuable natural heritage site with one of the largest remnants of ancient broadleaf forests and primeval coniferous forests containing Japanese cedar trees thousands of years old, Yakushima Island, together with the Shirakami-Sanchi mountains of northern Honshū, became Japan’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993.

Photos : 石橋睦美 Mutsumi Ishibashi / Text : Yūji Fujinuma / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Jomon sugi / Yakushima / Yakusugi / World Heritage Sites / loggerhead turtle / Ramsar wetland

Plentiful rain and steep terrain – a recipe for spectacular scenery

Blessed with warm ocean currents and lush greenery, Yakushima Island lies around 60 km south of Cape Sata, the southernmost point of Kyūshū. The granite that forms the bedrock of the island is thought to have been uplifted due to tectonic plate movement around 14 million years ago. This roughly circular island, the seventh largest in Japan, has a circumference of just over 130 kilometres, an area of around 500 square kilometres, and is the seventh largest island in Japan.

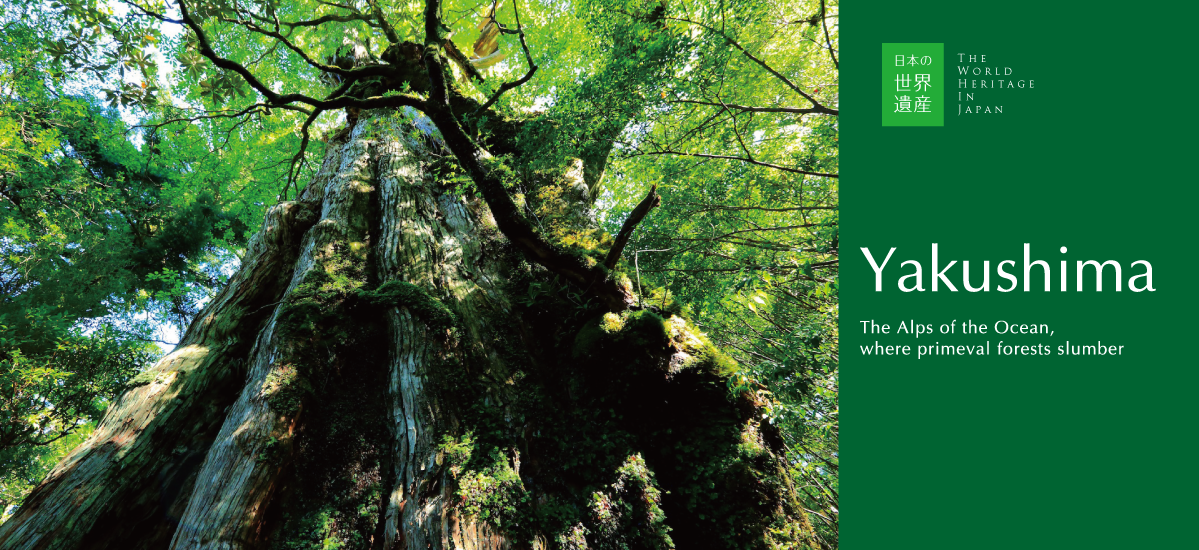

Viewed from aboard the ferry, Yakushima appears as a mass of forest-clad mountains rising straight up from the sea, which is how the island came to be known as ‘the Alps of the Ocean’.

Spreading out from towering Miyanoura-dake (1,936 m) in the centre, the island is dominated by mountainous terrain, with just a few pockets of flat land here and there around the coastline. Miyanoura-dake is the highest peak in the Kyūshū region (which extends from the island of Kyūshū itself, all the way south to Okinawa). In addition to Miyanoura-dake, there are at least forty peaks over 1,000 metres in height, and countless others over three hundred metres.

Locals say it rains thirty-five days a month here, and it’s not hard to see where that expression comes from! The low-lying coastal areas receive a massive 4,000 mm (157 in) annually. That’s wetter than the Amazon rainforest, and on a par with the wettest parts of tropical Borneo. The amount of precipitation more than doubles up in the mountains, with up to 10,000 mm (393 in) annually. Some of this falls as snow in winter, transforming the mountain landscape into an ethereal world of silver and white. But the high rainfall does more than just support lush plant growth. Water runoff from the peaks has carved a complex system of valleys and waterways that radiate out from each peak and join together to form fast-flowing rivers and spectacular waterfalls that tumble down the steep mountainsides.

Step from subtropical rainforest to subarctic alpine forest

Here on Yakushima, it’s possible to experience all four seasons in one day. With a difference in elevation of almost 2,000 m from the coast to the top of the mountains, the weather can be warm down around the coast, but cold and wintry up in the mountains. This has led to a vertical distribution of forest types on the mountainsides, with distinctly different plant types growing at each elevation.

At sea level, subtropical rainforest species like mangroves (Kandelia obovata), fan palms (Livistona chinensis) and Chinese banyans (Ficus microcarpa) flourish. Broadleaf evergreens such as Castanopsis species and willowleaf oak (Quercus stenophylla) are encountered at elevations between 100 and 700 metres. With many warm-temperate broadleaf evergreen forests having disappeared from the world, this extensive forest remnant in Yakushima is globally significant.

Broadleaf trees begin to make way for conifers at 700 metres, and this is where Japanese cedars (sugi in Japanese, or Cryptomeria japonica) and other conifers such as Japanese hemlock (Tsuga sieboldii) appear alongside broadleaf trees. The mixed broadleaf and coniferous forest belt persists until 1,200 metres elevation, above which comes the ‘yakusugibelt’. Yakusugi is the term given to Japanese cedar trees over 1,000 years old. If this were the Japanese mainland island of Honshū, the zone above 1,600 metres would be taken up by beech species, but due to a quirk of nature, these are not found on Yakushima. In their absence, this narrow zone up to 1,700 metres is given over to yakusugi with patches of Yakushima rhododendrons (Rhododendron yakushimanum). The mountain tops above this level take on a very alpine aspect. Forests give way to bamboo grass, with any trees that do manage to take root, dwarfed and hugging the ground.

Wildlife

In contrast with its many and varied plant species, Yakushima has only a small number of endemic mammals, including the yaku-zaru (Yakushima macaque) and yaku-shika (Yakushima deer), but none of the native wildlife such as rabbits and wild boar typically found in mainland Japan. The endangered loggerhead turtle lays its eggs on the beaches in the northwest of the island, with Nagata-hama being its main nesting ground in the Northern Pacific region. In 2005 this area gained protection under the Ramsar Convention, an international treaty that provides a framework for wetland conservation.

The secret to longevity deep in the forest

The stars of Yakushima are undoubtedly the ancient Yakusugi. The longevity of these trees is due, rather unexpectedly, to the challenging growing conditions on the island. The granite bedrock and steep terrain mean that there is little topsoil to support the trees. To compensate, they are forced to sink their roots directly into the bedrock to gain a toehold and to find nutrients. An additional challenge is the high rainfall, which, while keeping the roots moist, constantly leaches out the limited nutrients available. The result has been that on Yakushima sugi, generally a fast growing softwood, grow extremely slowly. With very little girth added to the trunk year on year, the annular rings are closely spaced and the resin content is high. This results in decay-resistant trees with unusually hard wood, which are far less susceptible to the natural age-induced decline that affects the rest of their species.

The oldest dated tree, Daiō-sugi (King Cedar), is believed to be over 3,000 years old. The biggest of the sugi, with a height of 25 metres and a circumference of 16 metres, is the Jōmon-sugi, which, because of its size was thought to have been as old as 7,200 years. However, the Jōmon-sugi has recently been dated at something over 2,000 years old. Other sugi well-known enough to have been given their own names include the Yayoi-sugi and the Sandai-sugi.

How to coexist in harmony with this precious environment

Many of the ancient yakusugi that remain today survive because they were either inaccessible or unsuitable for milling in days gone by. Yakusugi timber has a beautiful wood grain, high in resin and resistant to decay. It has long been used in construction and boat-building. In the late 1500s, under the Toyotomi administration, yakusugi timber was used in the construction of Hideyoshi Toyotomi’s pet project, Hōkō-ji Temple in Kyōto. Later, during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) when Yakushima came under the exclusive control of the Satsuma Domain in Kyūshū, the people of Yakushima, unable to pay their feudal tithes in rice, paid in yakusugi timber extracted from the island’s mountains. Most of this high-value timber was in turn shipped to Kyōto, and was an important source of income for the Satsuma Domain.

Yakushima’s supreme value globally is the way that the people of this island have, from one generation to the next, lived within and cared for its spectacular natural environment. Now though, the environment is facing a very different danger from the logging that threatened the yakusugi in the past. Visitor numbers have soared since the island became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Issues such as rubbish and human waste, as well as degradation of hiking paths have come to the fore. Even if visitors can be persuaded not to drop their rubbish in the forests, hundreds and hundreds of people every day hike into the mountains to see the yakusugi and are bound to need to answer the call of nature at some point in the day, raising the question of what do with human waste out in the wilderness.

With so many visitors, the paltry soil around the trees has become trampled, and the roots are becoming exposed. Boardwalks have been constructed, but these in turn enable greater numbers of people to access the area, and people need to step off the paths to allow others to pass. These issues are difficult to solve and have become a burden on local financial resources. This is a dilemma faced by small communities all over the world where undeveloped natural environments suddenly become wildly popular tourist attractions. While tourism is a boon to local commercial operators, the environmental degradation it causes cannot be ignored.

In Yakushima, the town council has initiated an environmental conservation fund and hopes that visitors to the island will choose to support this initiative. Now that visitor numbers are beginning to threaten the very environment that tourists are coming to see though, perhaps a visitor contribution needs to be mandatory rather than just being optional. Indeed, it may even be necessary to cap the number of visitors during peak times in order to protect and preserve this magnificent World Heritage Site for the benefit of all, present and future.

Access:

Ferries and fast hydrofoils run from Kagoshima. Several flights per day land at Yakushima Airport. Excellent information in English is available here

https://www.japan-guide.com/e/e4651.html

Visitor Information in English:

Yakushima Town website:http://www.town.yakushima.kagoshima.jp/en/

Visitor guide: http://www.kagoshima-kankou.com/for/areaguides/yakushima/index.html