In the late 1800s, Tomioka Silk Mill was a state-of-the-art silk reeling facility and flagship factory at the forefront of the new Meiji Government’s measures to promote industry and bring Japan into the modern world. Mass production was implemented at Tomioka Silk Mill and an improvement in the quality of Japanese silk thread was pursued here through the adoption of European equipment and expertise. The 2014 registration of the Tomioka Silk Mill and Related Sites World Heritage Site was an acknowledgement of the historical and cultural value of this extensive mill complex and staff accommodation buildings, and three other sites related to cutting-edge developments in silk production from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photo : 青柳健二 Kenji Aoyagi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Silkworms / Sericulture / Japan World Heritage / World Heritage Sites / Meiji Period / Gunma Prefecture / Tomioka Silk Mill

French Director Paul Brunat Leads Modernization Programme

Silk thread was Japan’s leading export in the 1850s, the final years of the feudal Tokugawa Era. However, silk production was still a cottage industry relying on traditional techniques. Standards varied and not all the silk that Japan exported was top quality. The appearance of inferior Japanese silk thread on the international market began to threaten the country’s reputation. Proposals from foreign business interests to fund and build a modern silk mill were rejected by the Meiji Government, which instead set about building its own mill utilising European know-how.

The new mill complex was to be a state-of-the-art facility for both the production of silk and the development of expertise to support the industry in Japan. The basic concept was to introduce Western technology and employ foreign advisors and instructors. Female workers from all over the country were to be recruited and trained, before returning to their own regions to work as instructors themselves. The mill itself was intended as a model factory, as part of the government’s quest to increase production and disseminate the latest silk-reeling technology nationwide.

French engineer Paul Brunat, a silk inspector with a French company in Yokohama, was engaged as a technical advisor. After investigating a number of possible sites for the new mill, Brunat settled on Tomioka. The region had been a centre for silk production for centuries, making it easy to secure the silkworm cocoons needed to produce silk thread. Another factor was the availability of a large area of land on which to build the factory, and an existing irrigation network that could be used to supply the fresh water needed for silk reeling. As well as this, the coal required to fire the boilers for the steam engines could also be obtained locally.

A Bumpy Start to Japan’s Golden Age of Silk Exports

Construction of the Tomioka Silk Mill began in 1871 and was completed the following year. Auguste Bastien, a French engineer and architect sent to Japan to work on the construction of the Yokosuka Steelworks, was in charge of the design. Construction materials were to be sourced locally and much of the timber came from the government-owned Myōgi-sanroku forest, while the stone was quarried from hills around the nearby town of Kanra. A kiln was built in Kanra to produce the bricks, which were fired by Japanese tile makers from Fukaya, Saitama Prefecture, under the guidance of a Frenchman.

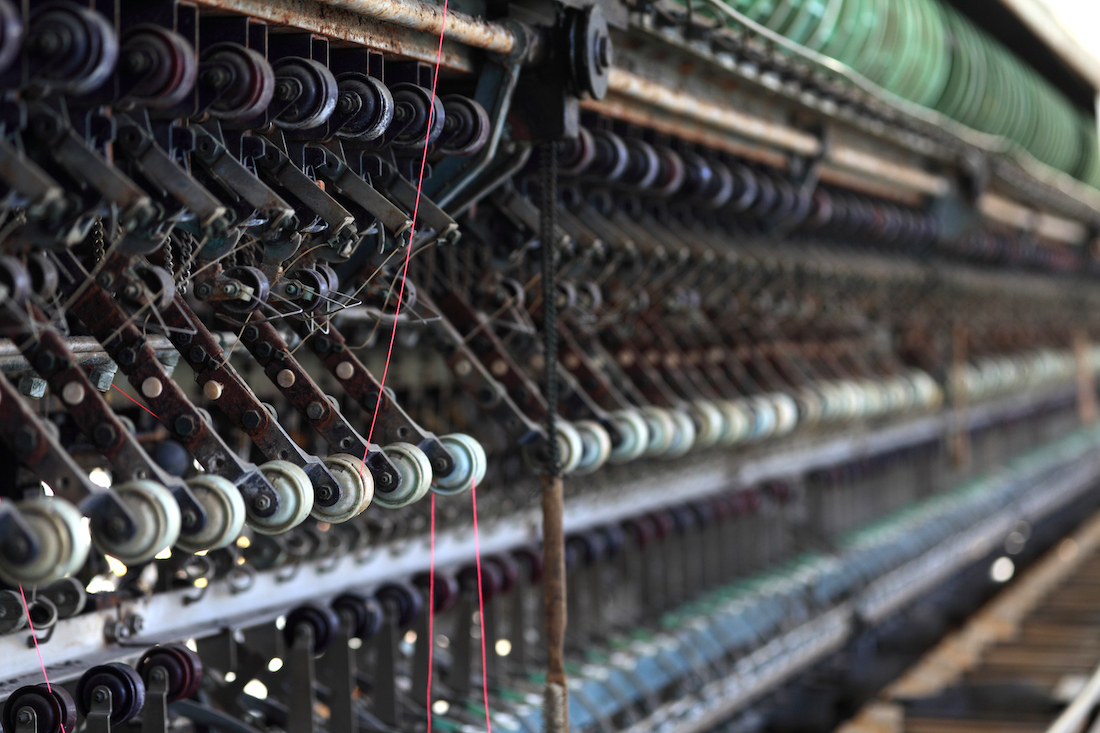

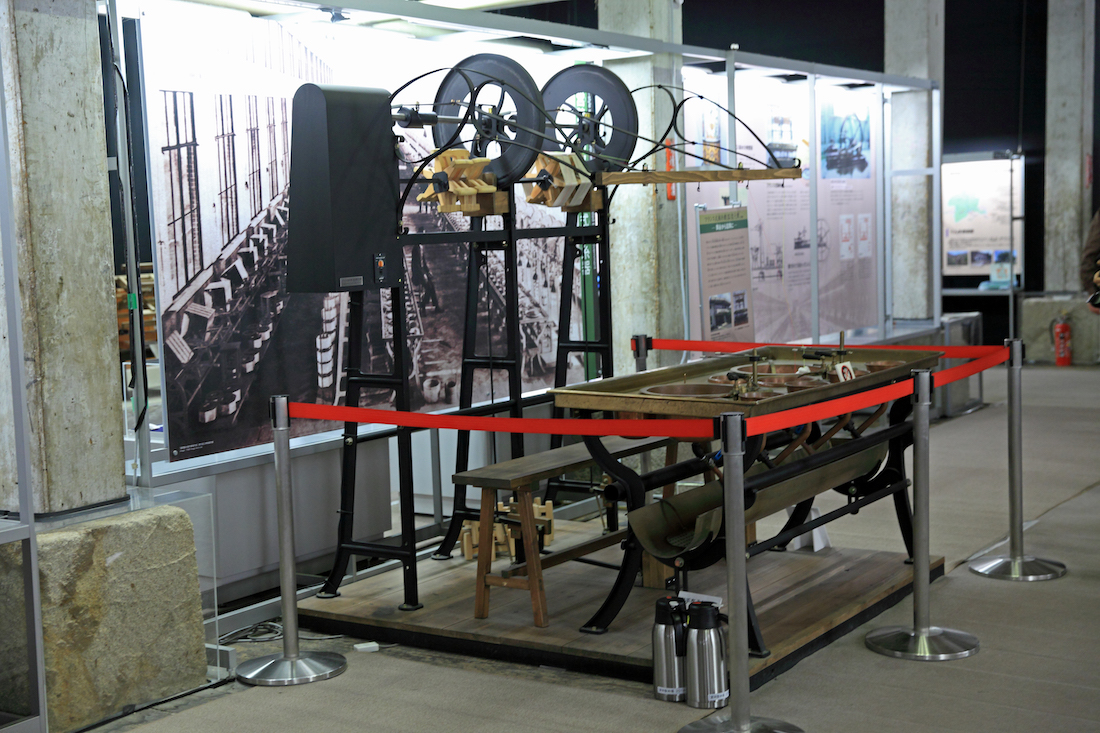

The silk reeling machinery itself was shipped over from France, and Brunat had it adapted to suit the Japanese physique. Once the female instructors (a group of technical experts from France) arrived, the mill was ready to swing into production. However, things didn’t go quite as smoothly as anticipated. The government had envisaged staffing the plant with Japanese women who would train here then return to their own provinces to teach others, but the women on whom this plan hinged were initially reluctant to come on board. Full production wasn’t achieved until a year after opening. Once in full swing though, the results were immediate, with the mill receiving an award at the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair.

Tomioka Silk Mill did not perform well financially at first, and continued to operate at a loss when Japanese managers took up the reins after Brunat and his team of French instructors left in 1875. Ownership of the mill was transferred to the Mitsui family in 1893 as part of the Meiji Government’s privatization programme. Then, nine years later, Tomioka Silk Mill became the property of the Hara company.

The almost four decades that the mill was operated by the Hara Company proved to be the height of silk production in Japan, with silk being the country’s biggest foreign exchange earner. The Hara Company worked to improve quality and increase production by installing additional silk-reeling machines and providing assistance to farmers, while the foreign exchange earned from silk exports stimulated modernization and strengthened Japan’s national power.

The Hara Company pulled out of the business in 1938 and the mill operated independently for a while as the Tomioka Silk Mill, before coming under the umbrella of the Katakura Silk Company (now Katakura Industries) and operating as a subsidiary. When operations at the mill ceased in 1987, Katakura Industries bequeathed the mill complex and all its buildings to the city of Tomioka.

Buildings Recall the Heyday of Japanese Silk Production

Various buildings associated with the Tomioka Silk Mill are located on the sprawling site of almost five and a half hectares (thirteen acres), largely unchanged since the time the mill was in operation. The design of the factory buildings relied on a well-established European construction method that utilised both Japanese and European skills and traditions. The timber-framed brick-infill construction consists of a structural skeleton of timber posts and beams for walls and roof, with sections of brickwork laid between the timber uprights to form the walls.

The main building, the silk-reeling plant itself, stretches 140 metres east to west and is around twelve metres in width. The orientation of the building allows plenty of natural light through the many south-facing windows, a vital aspect of the design considering that there was no electric lighting in Tomioka at the time of construction. The interior is a large airy space designed without any internal pillars that would get in the way of operations. As many as five hundred women worked here at one point, operating the three hundred silk-reeling machines. The east and west cocoon warehouses, each 104 metres long and twelve metres wide, are placed at either end of the silk reeling building, with the three buildings together forming a U-shape. The cocoons were stored on the upper floors of the cocoon warehouses, which could be opened up to allow air to flow through and keep the cocoons cool in summer.

Taking pride of place is a riveted iron water reservoir with a 400-ton capacity, the oldest domestically-produced iron structure in existence, and a valuable artefact from the early days of the silk-reeling mill. This water tank, originally used to provide water for the mill’s steam engines, was designated an important cultural property in 2006. Other remnants of the original Meiji Era factory include a boiler plant containing the steam engines that once powered the factory, and the original brick waste-water drainage system.

Brunat House, the residence of the first director Paul Brunat, is a stylish building designed in the American Colonial style, although Japanese architectural influences are evident throughout. The residence features a Japanese-style tiled roof and a veranda-like corridor that encircles the house. A nod to the home’s French connections can be found in the basement, which is an extensive brick cellar built to store food and, of course, wine.

Sericulture Sites Tell the History of Silkworm Farming

Tomioka Silk Mill and Related Sites comprises four properties, with three others in addition to the silk mill complex. One of these, the Tajima Yahei Sericulture Farm in Isezaki City, is an experimental farmhouse modelled as the ideal space for raising silkworms. The innovation here was architectural design features that allowed just the right amount of ventilation to keep the silkworms cool in summer. Silkworms were raised on the upper level of the farm house, and efficient cross-ventilation was ensured through the use of openings on all four walls, as well as a ventilation structure known as a sō-yagura running the length of the roof ridge. This consists of a section of raised roof ridge with sliding panels that can be slid open or shut to control the flow of air.

The third site, Takayama-sha Sericulture School, an educational institute in Fujioka City, was established by former village head Takayama Chōgorō, who developed and taught the seion-iku sericulture method, which relied on careful observation and control of temperature, ventilation and humidity levels in the rooms where silkworms were raised. Takayama’s method combined the strengths of two other sericulture systems, ondan-iku (raising silkworms in a warm room), and seiryō-iku (a method that relied on ventilation for cooling). The level of instruction at the Takayama Sericulture School was internationally renowned and silkworm farmers who came here to study were able to return to their regions and share what they had learnt. Although few of the original school buildings remain, their stone footings can still be seen and the main school building and the nagaya-mon (a front wall combining a covered entrance gate and farm buildings) are still here to tell the history of the school.

The fourth property that comprises the World Heritage Site is the Arafune Cold Storage facility in the mountains of Shimonita. This is a natural refrigeration facility where silkworm eggs were kept cool to prevent them from hatching. Taking advantage of natural vents in the mountainside where cold air blows out from between the rocks, the facility was built by a former Takayama-sha student. Earthen-walled store houses were built over the cold air vents, supported by stone masonry foundations. The air blowing from the vents is a constant two degrees, even in summer. Three such natural refrigeration facilities were built, making it possible to store silkworm eggs and delay their hatching until needed, which made sericulture possible all year round. The store houses themselves no longer remain, but their stone foundations are still intact.

The demand for silk has dropped dramatically in recent decades and the Japanese silk industry, once the world leader, is today in decline. With each farmer that gives up rearing silkworms, a small piece of Japan’s cultural heritage disappears. This makes the Tomioka Silk Mill and Related Sites World Heritage Site, where Japan began its journey towards becoming a modern industrial state, all the more important when it comes to preserving knowledge of Japan’s traditional silk culture.

Tomioka Silk Mill and Related Sites

Tomioka Silk Mill, address: 1-1 Tomioka, Tomioka City, Gunma Prefecture

Official Website:

http://www.tomioka-silk.jp/tomioka-silk-mill/