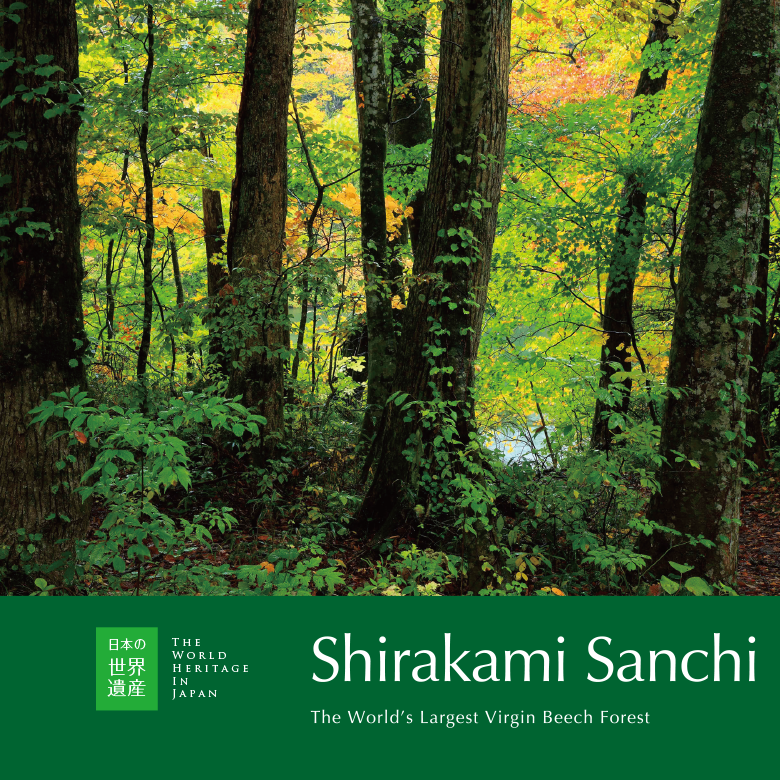

Facing the Sea of Japan in the remote north-west of Honshū lies the Shirakami Sanchi, a rugged and mountainous region straddling the prefectures of Aomori to the north, and Akita to the south. Protected for thousands of years by harsh winters and precipitous ridges, this pristine area was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993, ensuring that the precious ecosystem and diverse vegetation of the virgin Japanese beech forests that grow here remain intact into the future. Together with Yakushima Island in the seas south of Kyūshū, Shirakami Sanchi was the Japan’s first World Heritage Site.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photo : 石橋睦美 Mutsumi Ishibashi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Japan World Heritage / World Heritage Sites / Akita / Shirakami Sanchi / Aomori

Hardy Trees in a Harsh Environment

Shirakawa Sanchi, a vast forested wilderness of endless steep ridges interspersed with deep interlacing river valleys, stretches inland from the Tohoku region’s Japan Sea coast, encompassing the border between Aomori and Akita Prefectures. These ranges, with summits between 1,000 and 1,200 metres, are believed to have been uplifted from the seabed around 2,000,000 years ago, a time when there was considerable movement in the Earth’s crust. The mountains are still on the move and continue to be pushed up even now. Mukai Shirakami-dake (1,243m), the highest point, gains 1.3 millimetres in height each year.

Being located near the Sea of Japan coast, the Shirakami Sanchi region bears the brunt of the weather coming across from the Asian continent. In winter, dry continental winds pick up water vapour from Tsushima Warm Current as the air flows across the Sea of Japan. This moisture-laden air results in vast amounts of heavy, wet snow being deposited in the mountains and valleys of Shirakami Sanchi. The mountains fall silent as the temperatures drop to minus 15℃. The annual precipitation here is around 3,600 millimetres; three times that of the surrounding lowlands. Of this, up to 1,500 millimetres falls as snow.

The harsh environment of Japan’s northern provinces has sustained the forest here since ancient times; the cold, damp climate providing favourable conditions for Japanese beech (Fagus crenata). Known as buna in Japanese, these huge deciduous broadleaf beech trees are widely distributed throughout the country, from Hokkaido’s Oshima Peninsula in the north to Kyūshū’s Ōsumi Peninsula in the south. The trees feature a smooth, grey bark and grow to a height of thirty metres, with a trunk circumference of up to 1.5 metres. Differences have been observed in the growth habit of trees on the Sea of Japan side of the region, compared to those growing on the Pacific Ocean side. Trees in the high snowfall Sea of Japan area develop tall, straight, single trunks, while those in the high rainfall Pacific Ocean area tend to branch from near the base into multiple sturdy trunks. The leaves of the trees are ovate and approximately eight centimetres in length, being slightly bigger and more rounded on the Sea of Japan side of the island compared to those that grow on the eastern side.

A Perpetual Forest, Untouched and Unexplored

Studies reveal that beech forests have covered this region for 8,000 years or more, dating back to at least the mid-Jomon Period (14,000 – 300 BCE), the same time that the culture of eastern Japan began to develop. The people of that time were hunter-gatherers, so it goes without saying that the rich forests throughout the country played a vital role in their survival.

Satellite imagery acquired through the Landsat programme shows that the Shirakami beech forests extend some 45,000 hectares over the Shirakami Sanchi region and its environs. Of that, around 16,000 hectares consists of pristine, virgin beech forest. This untouched area comprises the World Heritage Site, which, including its surrounding buffer zone, covers 16,970 hectares.

Successive generations of beech trees have grown undisturbed in this perpetual forest for thousands of years. Japanese beech trees have an average lifespan of around two hundred years, but here it is not unusual to find trees as much as three hundred years old. Trees of all ages and stages exist side-by-side, from saplings to mature trees; from ancient trees to the fallen logs of trees that have died.

When an ancient tree dies, light fills the area that was previously shaded by its enormous spreading branches, and new life begins. This constant cycle of beginnings and endings is what has sustained the beech forests of Shirakami Sanchi for so long.

The Cycle of Life: Survival Against the Odds

Beech trees grow slowly and survival is tough. Surviving into adulthood is by no means easy for a budding young beech tree. Even if a seed germinates, it can quickly die without seeing a ray of sunlight. Many of those that do sprout will be promptly devoured by browsing wildlife. Even a seedling fortunate enough to take root in a spot that the sunlight reaches, will only grow around twenty centimetres each year, and even then might wither after two or three years.

Prospects are much improved for saplings that survive four or five years, but they still have a long road ahead. After forty years, the young tree can expect to attain a height of only five metres, with a trunk diameter of little more than ten centimetres. And the tree is still a long way off bearing fruit. That won’t happen until it makes it to the age of seventy or eighty years. Even then, mature trees bear fruit only once every three years or so, and it is only every seven or eight years that a significant proportion of the trees flower and bear fruit at the same time, resulting in a bumper crop of beech fruit and seeds.

Foliage thickly covers the wide-spreading branches of the mature trees in spring, preventing the spring rains from directly hitting the forest floor and damaging the delicate soil structure. Then, in summer, the leaf canopy protects the soil from moisture evaporation. The fruit drops to the ground just before the leaves do in autumn, ensuring that the seeds are covered in a rich layer of leaf litter as the tree sheds its leaves. This leaf litter is estimated to amount to around 2.8 tons per hectare, annually. These fallen leaves have an important job to do, breaking down into a rich humus that absorbs and stores moisture from the rain and from the thawing snow. The decaying leaf litter also provides the perfect habitat for insects and microorganisms. Essential nutrients for germinating trees and plants are also provided by decomposing fallen logs, which contribute to the maintenance of a rich forest ecosystem.

Strict regulations protect the precious forest ecosystem

The virgin beech forest cloaking the mountains of Shirakami Sanchi is the largest in the world, with natural features that have been of great academic interest for hundreds of years. Rich in biodiversity, the forest is home to over 500 different species of plants. A great variety of plant communities co-exist here, including many large deciduous broadleaf trees such as katsura, harigiri (Kalopanax septemlobus) and Japanese hop-hornbeam (Ostrya japonica), in addition to the beech trees.

Over two thousand species of animals, birds and insects inhabit the forest. The Japanese serow, designated a “special natural monument” thrives here, having been brought back from the brink of extinction. Two other inhabitants with natural monument status are not so fortunate. Both the golden eagle and the black woodpecker are endangered species. In contrast, and far from being threatened, the native sika deer has made quite a nuisance of itself in recent years and rapid measures are being taken to control its numbers in order to maintain the balance of the precious ecosystem.

As part of the plan to preserve this natural wilderness, no tracks have been cut into the heart of the Shirakami Sanchi area, and there are no plans to establish any in the future. Since becoming a World Heritage Site, access to the central part of the area has been restricted. Access is strictly prohibited on the Akita Prefecture side, while the Aomori Prefecture side can only be entered with permission.

However, the protected core of this World Heritage Site is not the only place in the Shirakami Sanchi where the beech forests can be seen. There are many giant trees over 200 years old along the Shirakami forest hiking trails around the protected area. These hiking trails offer scenery similar to that in the centre and are open to visitors. The Jūniko Lakes are a cluster of thirty-three lakes and ponds nestled within the vast beech forest, that delight visitors with their mysterious other-worldliness and incredibly clear water. Additionally, the World Heritage Site beech forests in the foothills of Mt Shirakami-dake can be seen in the distance from the Shirakami Line, a gravel road (part of Prefectural Route 28, closed in winter) that traverses the northern section of the Shirakami mountain ranges.

Location

Aomori Prefecture: Ajigasawa-machi, Fukaura-machi and Nishimeya-mura. Akita Prefecture: Fujisato-machi.

Enquiries

Shirakami Sanchi Visitor Centre

Kanda 61-1, Nishimeya, Nakatsugaru-gun, Aomori Prefecture, Japan

Phone: 0172-85-2810

http://www.shirakami-visitor.jp

Access

40 minutes by car from JR Hirosaki Station