Japan’s unique landscape is filled with breath-taking beauty and vistas that inspire and delight. In this series, photographer Kenji Aoyagi brings us significant landscapes, rich with history and worthy of preservation.

The time we head off to explore the canals and wetlands of Ōmihachiman, a historical castle town and Edo Period centre of commerce not far from Kyōto, in Shiga Prefecture.

Text and Photos : 青柳健二 Kenji Aoyagi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Important Cultural Landscape / Canals / Japan's Significant Landscapes Series / Edo Period / History / Ramsar wetland / Shiga Prefecture / Wetlands / Ōmihachiman

A Stroll Back in Time

Ōmihachiman, a small city located on the eastern side of Lake Biwa, Japan’s largest lake, is known as the birthplace of the famed Ōmi merchants. These merchants and financiers, who emerged in Ōmihachiman and whose activities spread throughout Japan, were renowned not only for their commercial know-how, but also for their business ethics and social responsibility. Some of the lovely old former residences and warehouses of the Ōmi merchants around the Hachiman-bori canal have been converted into museums, galleries or shops and are open to the public, offering a glimpse into the distant past. Known collectively as the “Ōmihachiman Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings”, the area along the Hachiman-bori canal, including Himure Hachiman-gū Shrine and the merchant buildings on Shinmachi-dōri and Nagaharachō-dōri, is a nationally designated Important Preservation District for Historical Buildings.

It was a public holiday on the day I visited Ōmihachiman, and the streets around Hachiman-bori, with its white plaster-walled warehouses and former residences of the wealthy Ōmi merchants, bustled with visitors. The old streets and buildings here are regularly used as film locations for period dramas such as Asahi Television’s long-running series Abarenbō Shōgun (“The Unfettered Shōgun”) or the 2012 live-action version of the samurai manga epic , Rurouni Kenshin. Strolling these Edo Period streets, it’s easy to imagine you’ve taken a step back in time.

As I wandered about the old town, dropping down from street-level to walk beside the canal, popping up and down stone steps, crossing bridges or ducking under them, I came to realise that exploring the historical quarter of Ōmihachiman is a three-dimensional interactive experience!

Still an Important Part of the Economy into the 20th Century

In 1585, young feudal lord Toyotomi Hidetsugu was given the governance of Ōmi Province. He established Ōmihachiman, a castle town at the base of Hachimanyama, the hill where his uncle, Toyotomi Hideyoshi had built Hachimanyama-jō Castle. To protect the hilltop castle and the administrative buildings below it, Hidetsugu had a moat excavated, drawing water from nearby Lake Biwa. The Hachiman-bori moat and canal measured roughly fifteen metres wide and six kilometres long, and linked the town of Ōmihachiman to the lake.

The role of the Hachiman-bori moat and canal system was both defensive and commercial. Ōmihachiman was located strategically near the Nakasendō Highway that connected Edo to Kyōto, and the Lake Biwa shipping route that brought goods from the Sea of Japan to Kyōto — two of the most important trade routes of the feudal era. Ships using the lake were required to call in at Ōmihachiman, meaning that Hachiman-bori played a major role in the growth and prosperity of the town.

Toyotomi Hidetsugu met with an unfortunate end only a few years after establishing the castle town, and the castle itself was abandoned and demolished soon after. However, due to the free market and open guilds policy that had been implemented by Oda Nobunaga, Ōmihachiman and its successful merchants continued to grow and prosper long after the demise of the Toyotomi family. In the heyday of Ōmi Province, Ōmihachiman was as busy as the city of Ōtsu, now a major city and the Shiga prefectural capital.

Hachiman-bori continued to support the local economy until after the Second World War, when the rise of road and rail transport saw the canal fall into disuse. Once canal maintenance such as silt removal ceased in the late 1950s, the water quality quickly deteriorated and by the 1960s, the canal had fallen into disrepair. The once clean waterway was choked with weeds and had become little more than a putrid open sewer. There was even talk of filling the canal in and getting rid of it entirely.

Japan’s First Designated Important Cultural Landscape

However, 2006 saw a huge reversal in Hachiman-bori’s fortunes. In January 2006, the canals and waterways of Ōmihachiman, collectively known as Ōmihachiman no Suigō (the Ōmihachiman Riverside District), were selected as the first of Japan’s newly categorized “Important Cultural Landscapes”. The Ōmihachiman Riverside District extends from Lake Nishinoko, located just north of the old town, and includes the reed belt, marshlands and canals in between the lake and the town.

Cultural landscapes are defined by the Agency for Cultural Affairs as being “landscape areas that have developed in association with the modes of life or livelihoods of the people and the natural features of the region, which are indispensable for the understanding of our people’s modes of life and livelihoods” (Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 5 of the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties, 1950).

That’s a lot to digest, but the definition refers to landscapes born out of Japan’s culture(s) and ways of life. Examples include landscapes such as water-filled rice fields, ploughed fields, irrigation channels, fishing villages and mountain villages. To put it another way, I’d say a Japanese cultural landscape is a landscape born out of typically Japanese solutions to the challenges of working this land; a landscape inherited from our ancestors and created over generations in accordance with the rhythms of daily life.

These cultural landscapes are such a familiar part of daily life that their value can easily be overlooked. Systems established to protect cultural landscapes prompt us to consider their true value, to protect them locally, and to ensure that they are passed down to the next generation.

Cultural Landscapes deemed to be of particularly high value may be further designated as “Important Cultural Landscapes”. As of June 2020, sixty-four more such landscapes have been designated in addition to Ōmihachiman, bringing the current total to sixty-five.

Local Grassroots Awareness Key to Preservation

How did the neglected canal system, having fallen into such a state of disrepair, then come to be designated Japan’s first Important Cultural Landscape? This considerable achievement has been attributed to the local residents’ high level of sensitivity to the importance of preserving their landscape.

A local movement to preserve the canal system emerged in around 1972, and a preservation society, the “Yomigaeru Ōmihachiman no Kai” was established. The canals were dredged and painstakingly restored to their former state. Perhaps it was the fact that the initiative was led by local residents rather than the government or municipality that singled out the Ōmihachiman proposal as being unique, and led to the Ōmihachiman Riverside District being designated Japan’s first ever Important Cultural Landscape.

Cruising the Scenic Canals Like a Feudal Lord

Lake Nishinoko was once just one of many lagoons or naiko (attached lakes) located around the perimeter of Lake Biwa and associated with wetlands and rivers flowing into the main lake. In the past, channels connecting these lagoons to the main lake allowed people and aquatic life to move easily between the bodies of water but in the past hundred or so years, many naiko have been drained and filled in. Lake Nishinoko somehow managed to avoid this fate, making this registered Ramsar wetland area all the more rare and precious.

The fast-growing (up to four metres per year) common reed, known in Japanese as yoshi, grows thickly around the banks of Lake Nishinoko. The reed belt forms an important ecosystem and hosts a wide range of aquatic creatures and birdlife, including, naturally enough, the reed warbler. The reeds are still used to make a variety of goods including sudare screens and blinds, and were once shipped all over Japan by the Ōmi merchants.

Although there is currently a slump in the reed-cutting and manufacturing industry, as well as a shortage of people to continue this traditional work, the canals and wetlands that comprise the Ōmihachiman Riverside District remain an important cultural landscape that continues to play a vital part in people’s lives, as it has for over four hundred years.

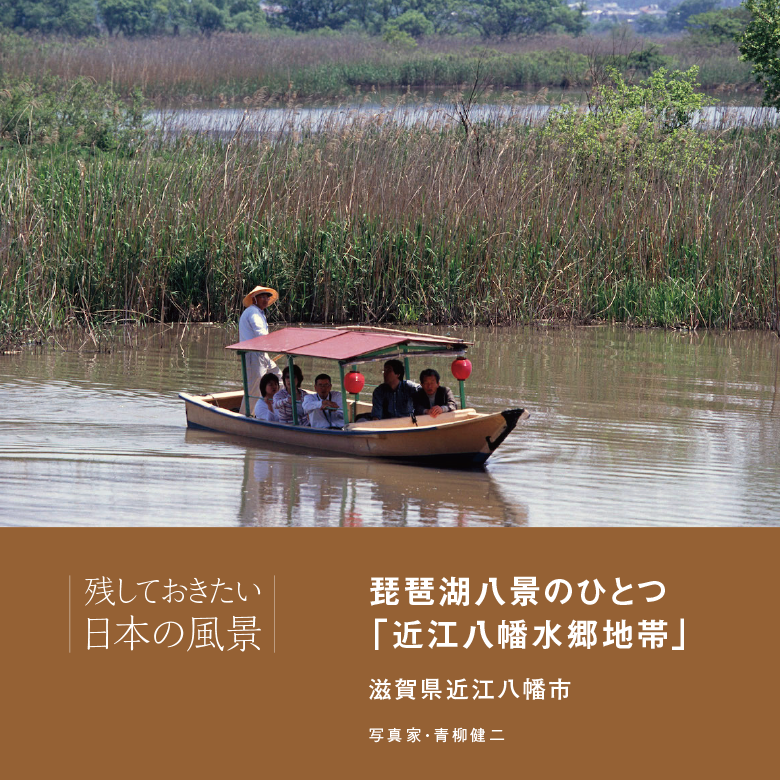

The scenic labyrinth of canals that characterise the landscape between Ōmihachiman and Lake Nishinoko is counted among the Eight Famous Views of Lake Biwa. Cruising the canals that meander through the meadows and marshlands between Ōmihachiman and Nishinoko in a man-powered canal boat propelled by a huge stern oar is an experience unique to Ōmihachiman.

And you’d be in illustrious company should you choose to do so! Young Toyotomi Hidetsugu, when he wasn’t off fighting battles, is said to have spent time messing about in boats on the waterways around Ōmihachiman, in imitation of the aristocrats of the imperial court of centuries earlier.

Ōmihachiman Riverside District

Access: Ōmihachiman Station is on the JR Tokaidō Line or JR Biwako Line, approx. 35 minutes from Kyōto Station. The old town district is about two km from the station and can be reached by bus or taxi from Ōmihachiman Station.

Information: Ōmihachiman Station North Exit Tourist Information Office (phone 0748-33-6061) provides pamphlets and information on attractions in the area and detailed information on canal boat tours.

This useful and informative pamphlet provides more information on Ōmihachiman and the Riverside District.