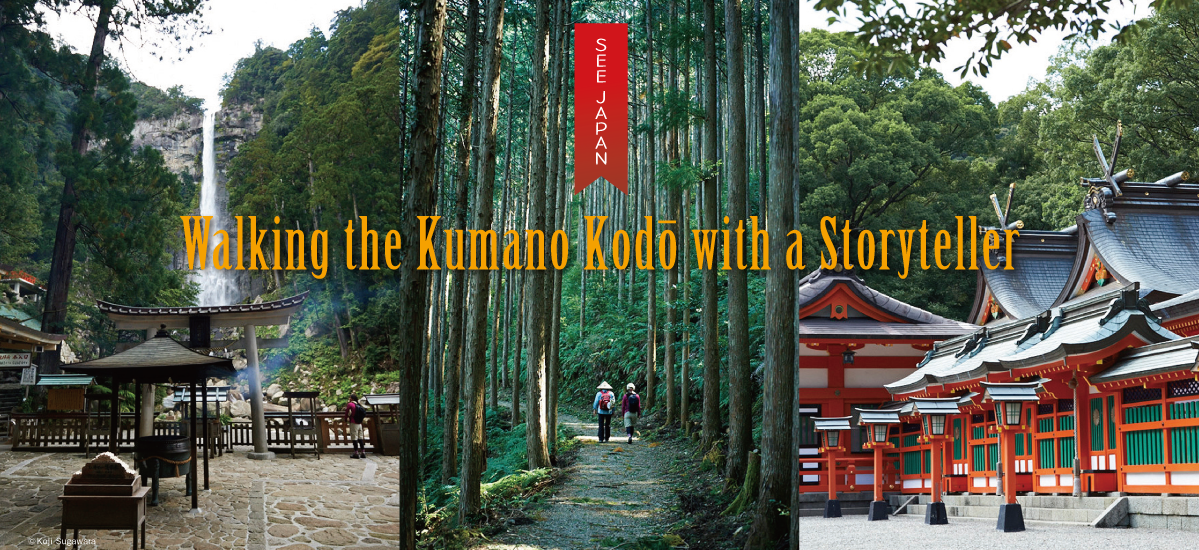

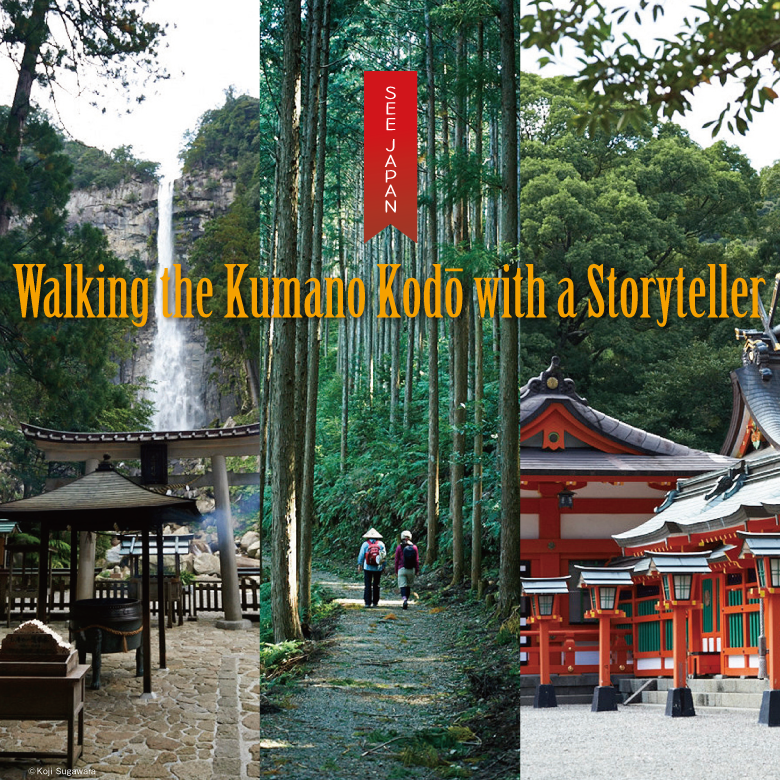

Kumano pilgrimages were all the rage among members of the imperial family during the Heian Period (794 – 1185). This fervour spread to the samurai and poets, and even to commoners, who began to set off for Kumano in their droves. The Nakahechi route was so busy, in fact, that the processions of pilgrims along its path were referred to as “the march of the ants”. Following in the footsteps of countless historical figures, I set off along this path of prayer with my walking companion, storyteller and guide, Emiyō Katō.

Text : 栗山ちほ Chiho Kuriyama / Photos : 菅原孝司 Koji Sugawara / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Kumano Kodō / Hiking / Kumano / Shrines / Kii Peninsula / Wakayama Prefecture

The Nakahechi route, well-trodden by the aristocracy of the past

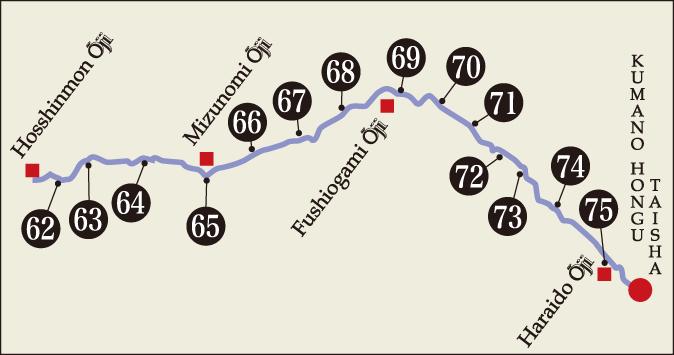

Four main pilgrimage routes lead to the Kumano Shrines. The Iseji route approaches the Kumano Shrines from Ise-jingū Shrine on the east coast of the Kii Peninsula; the Kohechi route leads from Kōyasan in the mountains to the north: Ōmine Okugake-michi is the route used by the mountain ascetics to reach Kumano from Yoshino; and finally, the Nakahechi route, that branches off the Kiiji route from Ōsaka and heads into the mountains. All of these routes end at the grand shrine of Kumano Hongū Taisha. After visiting Kumano Hongū, pilgrims then proceed to Kumano Hayatama Taisha and Kumano Nachi Taisha grand shrines. Together these three grand shrines are known as the “Kumano Sanzan”. Pilgrims generally make a point of worshipping at each of them in turn.

On this trip, I walked just one section of the Nakahechi route. The Nakahechi is the old imperial route that starts out as the Kiiji route along the west coast of the Kii Peninsula before heading into the mountains and finally arriving at Kumano Hongū Taisha.

As we make our way along the Nakahechi, storyteller Emiyō Katō regales me with ancient tales of the pilgrimage. Born and raised in the local area, Katō san is a veteran Kumano Kodō walking guide and member of the Kumano Hongū Storytellers’ Circle, well versed in the history of Kumano Kodō.

“The imperial family and the nobles came down the Yodogawa River from Kyōto to Ōsaka by boat. From the mouth of the Yodogawa River in Ōsaka, they made their way to Kumano. Along the way, there were several shrines known as ōji. These places were used as rest stops and lodgings for the nobles, which is why they are only found on the Kiiji and Nakahechi routes.”

We set off from Hosshinmon Ōji, our starting point. This ōji shrine marks the entrance to the vast Kumano Hongū shrine precinct. Behind the ōji is a former Buddhist convent where, eight centuries ago, Fujiwara no Teika, the illustrious Heian Period man of letters, is said to have stayed.

“Fujiwara no Teika accompanied Retired Emperor Go-Toba on his pilgrimages as an attendant. He went ahead of the emperor, ensuring that everything was in order regarding meals and accommodation. He was in his forties at the time, which was quite an advanced age in those days, and the Kumano pilgrimage was really arduous. In his journal, Teika repeatedly complained about how ‘gruelling’ and ‘hard’ the journey was.”

Twenty-three imperial households made the journey to Kumano; a grand total of 141 pilgrimages. The most prolific pilgrim was Retired Emperor Go-Shirakawa, who made thirty-four pilgrimages. Retired Emperor Go-Toba was next, with twenty-eight pilgrimages. Had he not been exiled after the Jōkyū Rebellion (a clash between imperial forces and those of the Hōjō clan, regents of the Kamakura shogunate), Go-Toba’s pilgrimage tally would probably have surpassed that of Go-Shirakawa. In modern times, when Crown Prince Naruhito walked the Kumano Kodō route in 1992, it was the first time a member of the imperial household had made the pilgrimage in 771 years.

Listening to Katō san as we walk the kodō, snippets of obscure history are brought to life as exciting tales of intrigue and adventure.

“It was while he was on the Kumano Kodō in 1160, that Taira no Kiyomori got word of the Heiji Rebellion. This was a struggle for power between two rival samurai clans, the Minamoto and the Taira. Minamoto Yoshitomo took the opportunity to stage his coup in Kyōto while Kiyomori was away on pilgrimage.”

Good Samaritans along the path of prayer

The return pilgrimage from Ōsaka to Kumano was a rigorous trek. However, it was believed that the harder the journey, the greater the benefit. By the time of the Edo Period, it was not just nobles making the pilgrimage through these rugged mountains, but also commoners, including women and children. In old documents, there is a description of nobles taking care of a blind woman who had collapsed on the path, even taking her with them to the next village.

“It was unthinkable in those days that nobles would come into contact with a common woman, but that sort of thing became quite normal along the Kumano Kodō. People had to pay to pass through the checkpoints along the way, and groups of prosperous pilgrims would pay for those who couldn’t afford it.”

The well-off made their way towards Kumano Hongū Taisha, increasing their own virtue as they went by offering charity to the poor.

In times gone by, the kodō served to connect the villages scattered along it and it passes through idyllic areas of farmland as well as dense forest. We walk past a Jizō statue (protector of travellers), placed there by villagers long ago in remembrance of a priest who had collapsed and died just outside their village. The Kumano Kodō is on UNESCO’s World Heritage list as the “Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes of the Kii Mountain Range”, but it is also a very human place, filled with tales of ordinary people and their compassion.

Reflecting on tales of the past, we make our way down to the Grand Shrine

The kodō trails have been continually improved throughout the centuries. The stone paving laid during the Edo Period has blended in perfectly with its natural surroundings over time, making me wonder how many people have trodden this path through the ages. We arrive at the final mountain pass on the Nakahechi and look down on Ōyunohara, the sandbank by the river where Kumano Hongū Taisha stood for centuries until it was partially swept away by floodwaters in 1889. The grand shrine was rebuilt on a nearby hill and now a massive ō-toriishrine gate stands on its former site. Up here on the pass is where Fushiogami Ōji shrine is. “Fushiogami” means to get down on one’s knees and pray. This is exactly what the pilgrims of ancient times would have done after their arduous climb, when they finally caught sight of the grand shrine itself.

“The celebrated Heian Period poet, Izumi Shikibu, started to menstruate when she reached Fushiogami Ōji. She composed a poem to lament the fact that she couldn’t complete the pilgrimage. There’s still a monument here to commemorate her.”

Hareyaranu

Miniukigumo no tanabikite

Tsuki no sawari to

Naruzo kanashiki

The skies do not clear

Clouds linger above me

Sorrow at my monthly affliction

Looking at the grand shrine from Fushiogami Ōji, I imagine the regret poured into this poem. Yet, I can’t help admiring the way great poets find words to express their experiences. Our journey today was just a small segment of the Kumano Kodō, but even so, I feel that my spirit has been thoroughly cleansed. By the time we reach the Grand Shrine, I’m feeling positively light-hearted.

Hongū-cho Hongū, Tanabe, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan

Further information:

Kumano Hongū Guide Association:

http://www.hongu.jp/en/kumano-kodo/walking/hongu-storytellers/

Tanabe City Kumano Tourism Bureau: