Japanese sake, with is subtly rich flavours and regional characteristics, garners attention worldwide. Behind every great sake are the dreams and passions of the brewers, and stories to move and inspire. In this series, Shōji Kobayashi, owner of a small sake shop in a Shitamachi neighbourhood of Tokyo, visits distilleries and breweries striving to create Japan’s finest sake. First up, we visit Yachiyoden Shuzō, a shōchū distillery and agricultural corporation in Tarumizu City, Kagoshima Prefecture, Kyūshū.

Photos and Text : 中島有里子 Yuriko Nakajima / Interviewer : 小林昭二 Shoji Kobayashi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Sarugajo Valley Distillery / Kagoshima Prefecture / Kyushu / Yachiyoden Shuzō / Sake / Shōchū / Distillery

Heading south from Kagoshima Airport along the Kyūshū Expressway, we make our way around the eastern shores of Kinkō Bay, the impressive volcanic form of Mt Sakurajima a constant presence on our right. We leave the main road and head inland along a winding country road, soon arriving at the beautifully maintained entrance way to the Yachiyoden Shōchū Distillery. Following the long driveway, we find ourselves in front of a large building where a group of men, all smiles despite the pouring rain, have come out to greet us.

The building that we head to first, the distillery itself, is a grand edifice with a red noren curtain and a sakabayashi cedar ball hanging at the entrance. Entering, we find ourselves in a vast open space with neat rows of earthenware pots set out across the extensive polished timber floors.

This is Yachiyoden Shuzō, a distillery in Tarumizu City, south Kyūshū, where shōchū is proudly brewed in these ceramic vats.

Reopening the Distillery

The Yagi Company was founded by Eikichi Yagi in 1928 and began producing an imo-jōchu (sweet potato shōchū) called Yachiyo, at the Yachiyo Distillery. The company enjoyed prosperity and provided employment for many, but almost fifty years later, in 1976, production of shōchū was suspended.

Having grown up surrounded by the hustle and bustle of the thriving distillery, third-generation Eiju Yagi, grandson of the founder, vowed to see the kura (brewery/distillery) restored within his lifetime.

In 2004, almost three decades after production was shelved and having borrowed vast sums of money, Eiju Yagi reopened the shōchū distillery in Sarugajo Valley – just as an unprecedented “imo-jōchu boom” began to sweep the nation. In December of that year, fulfilling the dream of reviving the kura, the first distillation of shōchū was released under the name, “Yachiyoden”, signifying the continuation of the Yachiyo tradition.

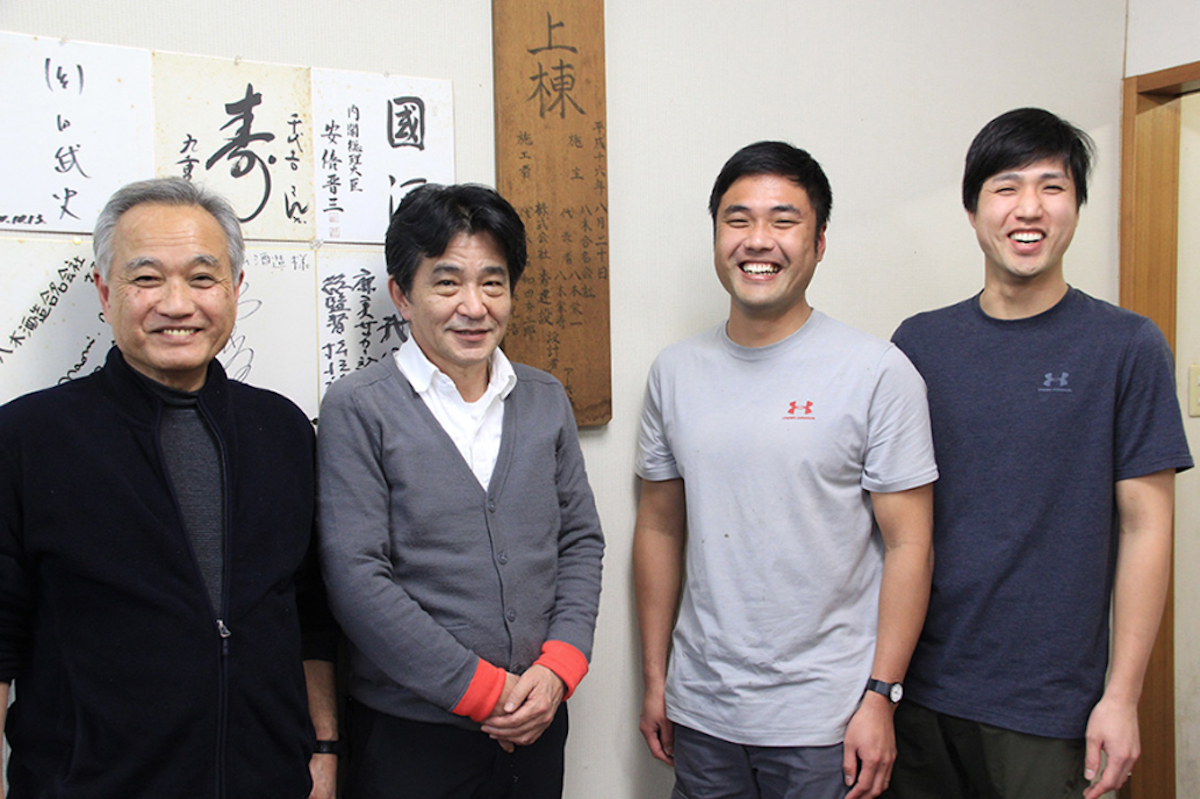

The journey was not without its bumps, but thanks to the support of many, and to Eiju’s own passion and enthusiasm, his dream became a reality. Eiju’s second son, Daijirō, declared that he wanted to join his father in the shōchū distillery before he’d even finished high school. The company was fortunate enough to attract the services of master brewer Masami Yoke, under whose watchful eye Daijirō set out on the path to becoming a master brewer in his own right.

Before long, Eiju and Daijirō were joined by university student eldest son, Kenjirō. Just as in the Legend of the Three Arrows, the trio have become a powerful force.

Shōchū Begins with Sweet Potatoes

Satsumaimo, the sweet potato, is the main ingredient of imo-jōchu (sweet potato shōchū).

Unlike ordinary potatoes, sweet potatoes don’t have a very long shelf-life and the quality of the shōchū depends on the freshness of this ingredient. Any damage or bruising is said to have an immediate effect on the quality of the shōchū.

This is where the family began running into immediate challenges. The ever-present fluctuations in the availability and supply of fresh agricultural produce were even more of an issue for Yachiyoden, as late-comers to the market. One of their earliest problems was how to secure a reliable supply of quality produce.

The solution? To grow the sweet potatoes themselves.

In 2009, Kentarō began work on producing the main ingredient, sweet potatoes. This was easier said than done, though, for a company new to the business of farming where, just as with sake brewing, experience and know-how are all-important. With a long wait-time between planting and harvest to see the results, any failure would meant having to wait until the following year to try again.

Downtime, when the company was not distilling shōchū, was spent bringing land under cultivation, planting and raising seedlings, and weeding and harvesting. All the while, Kentarō experimented with growing the perfect sweet potato, through a process of trial and error.

In 2018, Yachiyoden became the only sake producer in Japan to meet the eligibility requirements to become an Agricultural Production Corporation.

Currently, over 200 tonnes of sweet potatoes are harvested annually. This harvest supplies roughly 95 percent of the material required for the distillery’s shōchū brewing operation. By autumn 2019, that number is forecast to be 100 percent. Having begun with just one small field, the plantation now covers ten hectares.

Maintaining Tradition but Not Afraid of Change

Sweet potatoes harvested in the morning are brought immediately to the processing plant. The soil falls away easily from the smooth surface of these premium sweet potatoes. Once the tendrils and root hairs are removed, there is hardly any loss at all.

“Shōchū is a distilled liquor, but we approach the process much like wine makers.” says Kentarō. Just as many winemakers use grapes from their own vineyards, so too do the Yagis grow their own sweet potatoes.

There are other similarities, as well. To produce the “Moon” series of Tsurushi Yachiyoden shōchū, which had been under development since 2016, freshly harvested sweet potatoes were hung in a cellar for two months to raise the sugar levels. The “Crio” label, also part of the Moon series, is made from sweet potatoes stored at very low temperatures for six weeks. This new type of shōchū could be likened to ice wine or sweet, botrytized wines. According to the Yagis, these matured sweet potatoes come out of the steamer bursting with sweetness.

In February 2018, to commemorate becoming an Agricultural Production Corporation, Yachiyoden released the appellation, “Luther”, the first volley in their Farmer’s Bottle series. This shōchū is named after German thinker and reformer, Martin Luther, who is credited with having said, “Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree.” To capture the first eight years of Yachiyoden’s farming journey, this blend combines cured shōchū from 2009, the year they began farming, with fresh shōchū from 2017, their founding year as an Agricultural Production Corporation.

In a similar vein, “Mahler”, the second volley in the Farmer’s Bottle series, is inspired by a quote from early 20th century Austrian composer and conductor, Gustav Mahler: “Tradition is the handing down of the flame, not the worshipping of ashes”. This appellation is made entirely from the beniharuka variety of sweet potato, grown in their own fields without the use of harmful agricultural chemicals.

The mist folds gently in around us. In this beautiful distillery near the foothills of Mt Sakurajima, surrounded by the deep greens of the primeval Satsuma forest, Eiju Yagi’s sons take up the challenge of maintaining their father’s vision – the revival of Yachiyoden.

Sake Merchant Kobayashi Chats to the Yachiyoden Team

We spoke to Agricultural Production Corporation, Yachiyoden Shuzo Co., Ltd. CEO Eiju Yagi, Executive Director Kentarō Yagi and Master Brewer Daijirō Yagi.

Interviewer: Shōji Kobayashi, owner of sake store, Sake no Kobayashi.

Kobayashi: Eiju, I’m aware that you had a lot of challenges to overcome in getting the distillery up and running again. I read this booklet, which came together with the first release of Yachiyoden shōchū. (Kobayashi is holding a booklet written by Eiju Yagi entitled “Itte-koi Yachiyoden” (See you soon, Yachiyoden).

Eiju: That’s right. Even now when I read this I feel the tears start to well up. I think of all the people who helped us.

Kobayashi: And now you have your two sons working alongside you. Daijirō, you started at the distillery straight out of high school, right?

Daijirō: Yes, I came under the guidance of chief brewer, Mr Yoke.

Kobayashi: Then, six months later, Kentarō, you left university and came on board.

Kentarō: When I came back to the distillery, Dad was taking care of the financial side of things, but there were so many other things that needed doing as well. We were learning how to make shōchū, and had no clue as to how to market it. I started visiting sake shops all over the country at that point, and learnt a lot that way.

Kobayashi: But, once the the distillery had been reestablished, why go into agriculture?

Kentarō: We’d been buying in sweet potatoes from regular farmers, but as late-comers to this industry, it was hard for us to source the best sweet potatoes. If a farmer already had four established customers, we were then fifth in line, which meant we ended up with what was left over, not realising that the sweet potatoes would go bad over time. So we decided to try growing them ourselves.

Kobayashi: Producing the raw materials yourselves would have been pretty time-consuming. How did you get everyone to agree to the idea?

Kentarō: The first four years was just a series of failures. We employed over twenty people. When we weren’t making shōchū, we were growing sweet potatoes, but when we were busy in the distillery there was nobody out in the fields – which wasn’t ideal. Also, we ran into problems planting the same thing in the same place repeatedly. And workers would quit, too.

Kobayashi: So, you enrolled in grad school at Kagoshima University, right? What did you study?

Kentarō: Agriculture and yeast. Like, isolating shōchū yeast.

Kobayashi: And you now have some quite original ideas about yeast, don’t you? And you’re interested in using biotechnology to breed your seedlings. Are all the seedlings you use now raised using biotechnology?

Kentarō: “Biotech seedlings” sounds all very scientific, but it’s actually about having virus-free seedlings. We use material from the best sweet potatoes harvested the previous year, to propagate seedlings under sterile conditions. It’s way more costly than using seed potatoes, but because the plants don’t tend to become diseased, we can estimate and control the size of the harvest quite accurately.

Kobayashi: So, you’re making shōchū, you’re farming… isn’t it a lot of work keeping up with the company?

Kentarō: That’s right. We began with a thorough reevaluation of the operation and cost cutting measures. Streamlining our processes, reducing the amount of outsourcing we did, that sort of thing. We halved our workforce and focused on upping our skill level as a company with a small workforce. We managed to create more time, and also to pretty much double our time off. Now we only have to work shifts during the brewing period.

Kobayashi: I’ve heard that your sweet potatoes are amazing! But last year the weather was unseasonably bad and many distilleries had issues with limited production and supply of the ingredients.

Kentarō: We were lucky enough not to have had that problem. Also, I think I’m someone who likes to think things through while I’m working out in the field. If I try to do it sitting at my desk, I tend to get a bit bogged down.

Kobayashi: I hear you’ve built a new maturation cellar. What’s the reason you decided to focus on ripening and maturing the sweet potatoes, as you did for the “Tsurushi” and “Crio” shōchū styles?

Kentarō: I thought about how, with sweet potatoes that are used for cooking, they get sweeter over time if you leave them. Out of all the ingredients for making liquor, that really only applies to grapes and sweet potatoes. However, the first year, I managed to rot the whole lot! Now, the success rate for ripening is 99.5 percent.

Kobayashi: That’s amazing! These matured sweet potatoes have become a real asset for you. I think from now on though, there’s going to be mature sweet potato wars in this industry. Everybody’s got their eye on you! I wish you all the best with everything.

Yachiyoden Shuzo Co., Ltd. Sarugajo Valley Distillery.

Shinmidō Nabegakubo 1332-5, Tarumizu, Kagoshima 891-2111, Japan.

Website: http://yachiyoden.jp/