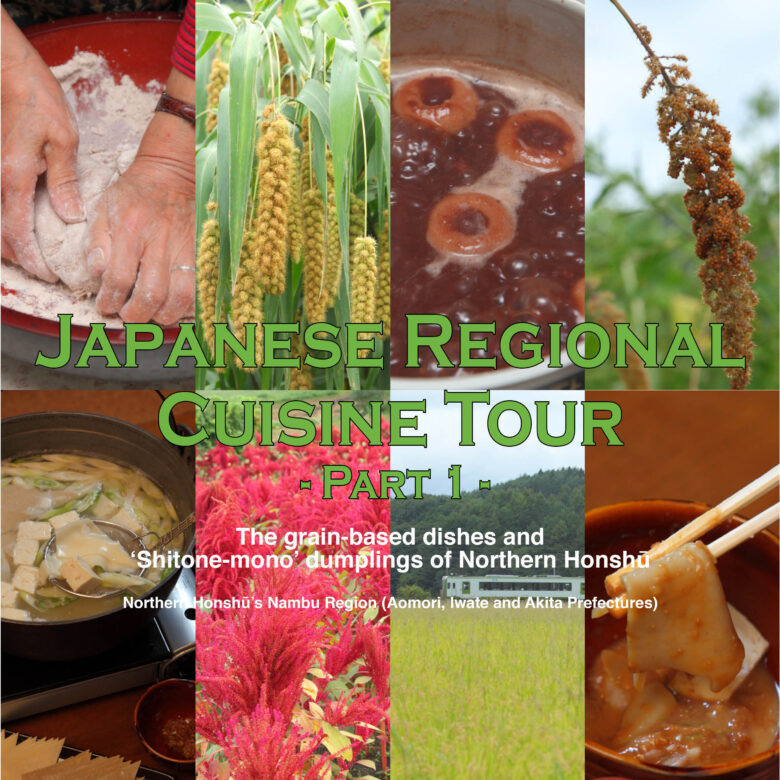

Japan’s much-loved traditional regional dishes – the essence of local history and culture served up in a bowl. Join us on a grand food tour of Japan’s provinces, in search of local soul food!

Text : 富山紀子 Noriko Tomiyama / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Aomori Prefecture / Iwate Prefecture / Japanese Regional Cuisine / Nambu Region / Iwate Galaxy Railway / Aoimori Railway

Aboard the Iwate Galaxy and Aoimori Railways

The Nanbu Region, which extends south from the Shimokita District of Aomori Prefecture and includes large parts of Iwate and north-eastern Akita Prefectures, is named for the powerful Nanbu Clan, who controlled the region until the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Due to a combination of vast mountainous areas, severe winters and limited arable land, rice cultivation here is extremely difficult. As alternatives, soy beans and grains such as wheat and buckwheat, and other cereal crops, including a variety of species of millet (common millet, foxtail millet and barnyard millet), have long been cultivated in the region. The tradition of preparing and serving regionally distinctive dishes utilising these local ingredients is still proudly continued today.

Amid the current health food boom, people in Japan are taking another look at millets and other rice alternatives. To learn how best to prepare and enjoy these grains, we climbed aboard the Iwate Galaxy Railway (Iwate Ginga Tetsudō, named for renowned local author Kenji Miyazawa’s Night on the Galactic Railroad) that runs from Morioka in the south, before transferring onto the Aoimori Railway that runs north to Aomori.

Morioka Station – Dining like feudal lords on ‘Wanko Soba’!

Presented to the diner as bowl after lacquered bowl of somewhat shorter than usual soba noodles, wanko soba earned its fame throughout Japan for the challenge to see who could down the most soba in one sitting. Despite wanko soba’s present reputation as a competition to see who can eat the most, this manner of offering small servings of buckwheat noodles one after another actually originated as a way of catering to large numbers of guests at banquets.

Because the traditional kamado cooking stoves of the past made it logistically impossible to boil huge amounts of soba noodles in one lot, it would have taken forever to get around to the last diner if each banquet guests were to be served their entire portion all at once. The solution, according to local wisdom, was to serve everybody in a succession of tiny but equal portions. ‘Wanko’ is the local name for the small lacquered bowls that each mouthful arrives in.

Although modern commercial gas cookers mean there’s no longer any fear of missing out on noodles, the tradition continues as a way of delighting guests and showing hospitality. Meals are served on their own trays, with condiments such as sliced spring onion, grated yamaimo (mountain yam) and maguro (bluefin tuna) sashimi to accompany the noodles. With one waiter on standby for each diner, ready to replenish bowls in a flash, we felt for all the world like feudal lords from a bygone era.

Wanko soba is a must-try local dish from local author Kenji Miyazawa’s favourite town, Morioka.

■ Azumaya Honten

1-8-3 Yanagidori, Morioka City, Iwate Prefecture

Tel: 0120-733-130

http://www.wankosoba-azumaya.co.jp/

Ninohe and Tomai Stations – ‘Yanagi-batto’ and ‘Hetchoko Dango’

Ninohe, Japan’s largest producer of lacquerware, is well-known for its Jōbōji Lacquerware, and for the Buddhist temple, Tendai-ji, where famous contemporary writer and Buddhist nun, Jakuchō Setouchi, delivered her open air lectures. Ninohe has also, since ancient times, been renowned for its grain production.

A dish that has traditionally been cherished by the people of this area is ‘hatto’, made from soba (buckwheat). Dishes called hatto are widespread and can also be found in Ibaraki, Tochigi and Fukushima Prefectures. Each region has its own way of preparing hatto, with slightly different ingredients, and even different folklore around how the dish got its name.

Depending on the kanji characters used to write it, the word ‘hatto’ can mean ‘prohibited’. Here in Ninohe, so the popular story goes, the local feudal lord decreed that buckwheat soba noodles were far too good for common folk, and banned the local peasants from eating them, hence the name, hatto!

Undaunted by this, resourceful peasants were determined to enjoy their delicious buckwheat one way or another! Rather than rolling the buckwheat dough out to form conventional noodles, the dough was shaped by hand into ‘willow leaves’. The Japanese word for willow is ‘yanagi’, so around here, hatto is known as ‘yanagi-batto’. Floating lightly on a shōyu (soy sauce) broth, the texture is fresh and quite different from regular soba noodles. According to the story, common folk would tuck into a hearty bowl of yanagi-batto, reasoning that since it was regular soba noodles that were banned, eating yanagi-batto wasn’t breaking the law in any way at all!

Ninohe is one of Japan’s leading sorghum growing areas, and another dish traditional to this area is hetchoko dango dumplings made from sorghum flour. Sorghum’s popularity has risen recently, along with the current concern around healthy food, but in the past it was considered inferior to rice because of its slight bitterness. Sorghum flour is made into a dough with either hot or cold water, and is used to make wonderfully moist dumpling snacks and dishes. These are a kind of ‘shitone-mono’ (pillowy things!), the local term used to refer to dumplings.

The name, ‘hetchoko dango’ (belly button dumplings) refers to the shape of these shitone-mono. The dough is kneaded to a soft ‘earlobe consistency’ and formed into flattened balls, each with a small belly button-like depression in its centre. The dumplings are boiled and added to a sweet porridge made from red azuki beans, similar to o-shiruko. A faintly bitter element can be detected amongst the sweetness of the azuki, but according to the rave reviews this dish is getting, that just makes the flavour all the more delicious!

We recommend trying hetchoko dango together with yanagi-batto.

■ Yoneda-koubou [Sobae-an]

24-2 Jumonji, Shimotomai, Ninohe City, Iwate Prefecture

Tel:0195-23-8411

A stopover in Karumai – Hot sake and soba scraps!

Karumai-machi is Japan’s top producer of grains other than rice. Harvest starts in around September and freshly harvested wheat, buckwheat and millets can be sampled and purchased at ‘farm gate’ outlets, roadside rest stops and specialty soba stores in the area.

One of the traditional ways of eating buckwheat locally is as ‘kakke’, or noodle scraps. After the dough has been rolled out and cut into noodles, there are always scraps left over from around the edges. While the noodles used to be reserved for customers, the kakke were taken home for the family to eat. Now, it’s the kakke that are taking centre stage.

Soba kakke is served o-nabe style, cooked at the table over a portable gas burner. The triangular kakke are heated in the broth, a few pieces at a time, along with tōfu and sliced leeks, and served with local miso paste and garlic as condiments. Soba kakke is best enjoyed slowly with a cup of hot sake.

This local dish flew under the radar for a while, but with the current movement towards revitalising small towns and rediscovering local cuisine, soba kakke is back in the spotlight. Autumn, when the grains are newly harvested, is a great time to treat yourself to soba kakke, but at the long-established ‘Furudate Seimenjo’ noodle shop in Karumai-machi, square kakke, made from both wheat and buckwheat, is available all year round.

■ Furutachi Seimenjo

8-139 Karummai, Karumai-town, Iwate Prefecture

Tel:0195-46-2301

Aomori Station – Keiran and soba mochi

‘Keiran’ is the Japanese word for hen’s egg and, just as the name suggests, keiran dumplings are shaped like eggs. Walnuts and anko (sweet bean) paste are worked into the centre of oval dumplings made from mochi (glutinous rice) flour and white rice flour. The dumplings are boiled, then placed in a delicately-flavoured clear dashi broth. Keiran was traditionally reserved for auspicious events and ceremonies, and despite being a regional specialty, it is not commonly found locally. However, it is available at restaurants that specialise in local traditional dishes.

The juxtaposition of the sweet anko with the savoury katsuo (bonito) and konbu (kelp) flavoured dashi will be a novelty for most visitors to the region, but the flavour of these handcrafted shitone-mono is unforgettably good!

Regular visitors to Aomori City make time to savour the homestyle cooking at ‘Inaka’, a restaurant specialising in local cuisine and Japanese dishes. The owner draws on her own memories of local Nanbu cuisine to produce dishes not found on any menu. Saying, ‘I think you’ll like this’, she served us soba dango – buckwheat dumplings on skewers fashioned from disposable chopsticks – yet another variation on the local theme of shitone-mono. The soba dango are first cooked in boiling water, then grilled and served with wild sesame miso sauce. The flavour of the buckwheat dumplings and the fragrance of wild sesame were heavenly – so good that I could have eaten any number of soba dango!

Having sampled just some of what the Nanbu Region has to offer, it makes me wonder how this area was ever considered impoverished in the past.

■ Inaka (Traditonal Japanese and Nambu Cuisine)

1-25-16 Chuo, Aomori City, Aomori Prefecture

Tel:017-722-5476