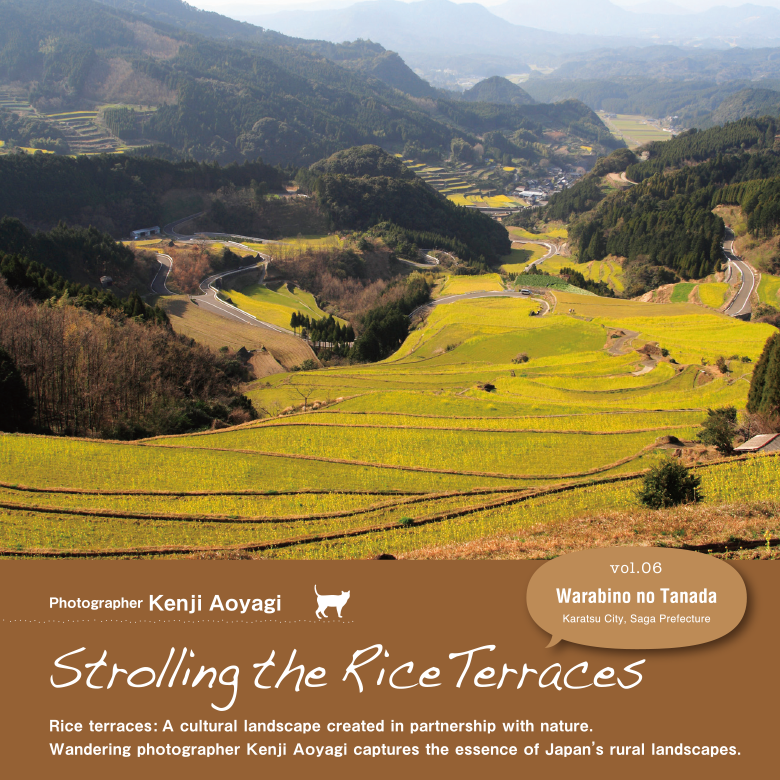

Carved into the side of Mt Hachiman-dake (764 m) in the Karatsu Ōchi-chō area of northern Kyūshū, the Warabino Rice Terraces are listed as one of Japan’s Top One Hundred Rice Terraces. The tanada (rice terraces) are located between 150 and 420 metres above sea level and trace the paths of five streams down the hillsides, converging just above the farming village below. From the air, these rice terraces, designated as an Important Cultural Landscape, resemble the five outstretched fingers of a gigantic hand.

Photos and Text : 青柳健二 Kenji Aoyagi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Karatsu City / Rice Terraces / Farming / Horticulture / Kyushu / Saga Prefecture / Warabino Tanada

Magnificent Stone Walls Reminiscent of Another World

The terraces at Warabino are separated by massive dry-stone walls constructed from natural stones and boulders of varying sizes. Compared to eastern Japan, where rice terrace embankments tend to be constructed from packed earth, dry-stone wall embankments are commonly used in western Japan. However, these walls are next level. From below, they look just like the majestic stone walls of a mountain castle – which is hardly surprising, given that they were constructed with the same techniques used for castle walls. Looking up, I’m overwhelmed by a sense of the sheer effort and determination of the people who built these terraces so long ago, and I can’t help but wonder what need drove them to extend their rice fields up a mountainside like this.

Comprising over 700 individual fields covering an area of 36 hectares, Warabi no Tanada is one of the largest of Japan’s Top One Hundred Rice Terraces. Without a farmhouse in sight as I contemplate these massive stone walls in their rugged mountain setting, I can’t help feeling as if I’ve stumbled across the stone ruins of some ancient Andean civilization!

These stone rice-terrace walls are said to be the highest in Japan, and some are over eight metres high. Looking down from the very top is enough to make me feel a little weak in at the knees, but the farmers pulling weeds out of the embankments have scaled the walls just like rock climbers. This is “skin of the teeth” rice growing – one of the farmers tells me they lost their footing and almost fell when they were startled by a big snake that came out of a gap between the rocks.

I notice a boulder next to a culvert, with the inscription “Shōwa 10” carved into it, suggesting that this particular wall was constructed in 1935. I’m struck by the ingenuity of the irrigation system here. Including this culvert, there are ninety-seven underground irrigation channels at Warabino Rice Terraces, carrying water from the reservoirs down to the lower terraces.

One September, I was lucky enough to be here at harvest time. Many of the individual rice fields in the terraces are relatively large, meaning that the rice can be harvested by combine harvester. As I watched, the tiny combine harvester made its way slowly between the heavily laden ears of rice.

Festivals are an essential aspect of farming for the folk of Warabino; not only an opportunity to acknowledge their gratitude for nature’s bounty, but also to bring the people of the village together. During the rice harvest, locals enact a traditional dance known as Furyū. Originally a form of victory celebration dating back to the Warring States Period (1467-1568), Furyū is now performed to pray to the deity of rice fields and harvests for a good harvest, or to give thanks after a bumper harvest.

Women in brightly-coloured costumes and sedge-woven hats dance in a circle around an orchestra of taiko drums, flutes and gongs. My attention was immediately attracted to the large gongs the musicians were striking, which reminded me of the gongs I’d seen in Balinese gamelan orchestras.

Rice cultivation is said to have been introduced to Japan from China and Southeast Asia but it would seem that a number of other customs were introduced along with cultivation techniques, with many Asian countries sharing customs around festivals, meals and types of entertainment. The people I met in Bali seemed to follow a similar lifestyle during the harvest season as the people of Warabino, harvesting in the fields during the daytime and entertaining themselves with song and dance in the evenings. And, of course, conducting festivals to give thanks to the gods.

As understanding of the cultural significance of rice terraces has grown in Japan in recent years, a number of events have been organised here at Warabino Rice Terraces to allow city folk to experience the rural lifestyle. These include walking tours and planting nanohana (rapeseed) in spring.

With an aging population and increasing urban drift, centuries-old rice terraces are being abandoned in many parts of Japan, but not here at Warabino. Even before the current resurgence of interest in tanada rice began, Warabino locals were determined not to be the generation that allowed their rice terraces to crumble into disrepair. “Now that our rice has begun selling, it feels as if we’ve been able to give back a little, to honour these stone walls that our ancestors put so much effort into building”, says a spokesperson from the Rice Terrace Preservation Association.

The rice variety grown here is Yume Shizuku, a relatively new cultivar certified under the Saga Prefecture Special Agricultural Crop certification scheme. Sold as Tanadamai “Warabino”, it is available locally from the Warabino no Tanada direct sales outlet.

The current interest in traditional rural landscapes such rice terraces goes hand-in-hand, perhaps, with modern-day concerns about knowing where our food comes from. However, that’s not the only thing that makes Warabino rice so popular. There’s also the security of knowing that the rice fields are irrigated with pristine water that flows from the hills – clean enough to drink, they say. The elevation of the rice fields also plays a part. The greater difference in daytime and night-time temperatures on the side of Mt Hachiman-dake compared to down on the plains means that the rice matures more slowly and has longer to develop its delicious flavour.