In early February, the coldest time of the year, water vapour rising from Suruga Bay is driven up into Mt Fuji’s foothills by the northerly airflow. This airborne moisture rapidly cools once it gets to the mountain and begins to form clouds that coil around Fuji’s southern flanks. Although the weather is comparatively dry and clear along much of the Pacific coast at this time of the year, clouds tend to form on the mountain on all but the coldest, stillest of days.

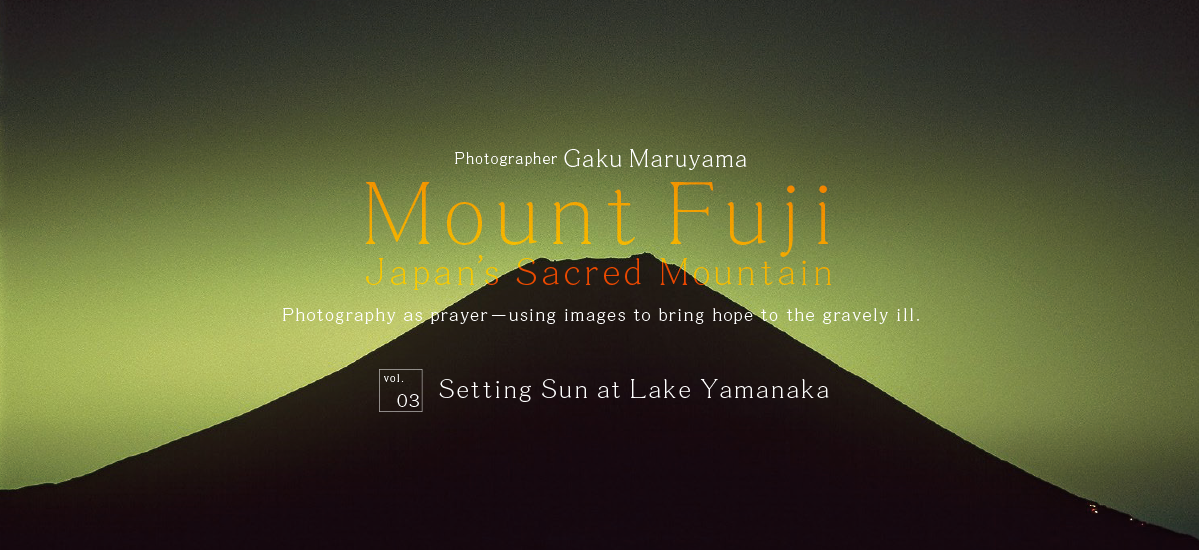

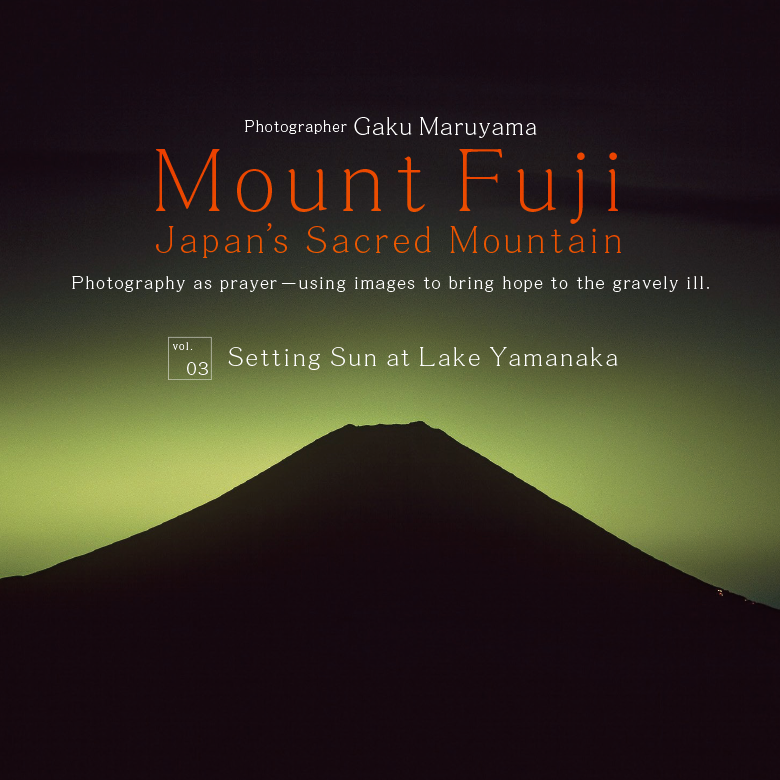

I was here at Lake Yamanaka to photograph the ‘Diamond Fuji’, a sun flare captured at the moment the sun hits the apex of the mountain and resembling the sparkle on top of a diamond. Having waited years for this moment, I watched as, under a rare cloudless winter sky, the magnificent evening sun began its descent towards the summit of Japan’s sacred mountain.

Seeing the sunset Diamond Fuji for the first time, people are amazed at how quickly it’s all over and done with. No sooner does the famous gleam appear than it’s gone, the sun disappearing behind the mountain. For me, what was doubly special was capturing the setting sun as it glittered on the icy surface of Lake Yamanaka, which had frozen over for the first time in twenty-two years.

Photos and Text : 岳 丸山 Gaku Maruyama / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : photography / Mount Fuji Photography Series / Lake Tanuki / Lake Yamanaka / Diamond Fuji

Capturing Mount Fuji

There are two types of Diamond Fuji – the ‘sunrise diamond’ and the ‘sunset diamond’. The sunrise diamond captured from Lake Tanuki, where the rising sun appears at the apex of the mountain framed by the trees on either side of the lake, is a particularly famous version of the Diamond Fuji. This shot can be lined up at around six in the morning in April or August, roughly two months either side of the summer solstice. Meanwhile, on the eastern side of the mountain, an iconic shot of the sunset diamond can be captured from Lake Yamanaka at around four in the afternoon, from October until February.

We’re lucky to have these clear viewing spots from which to capture the Diamond Fuji. With the speed of the Earth’s rotation at the latitude of both lakes being approximately 380 metres per second, the moment when the distant sun lines up with the apex of the mountain is fleeting indeed.

Getting the sun centred directly over the peak of the mountain is what makes or breaks a Diamond Fuji shot. Locations from which the phenomenon can be observed at Lake Tanuki are limited, meaning that there are only about five days when the sun appears at the top of the mountain when viewed from the available photography spots. Perversely, this restricted time-frame actually makes it easier. Assuming that the weather cooperates, it’s really just a matter of claiming a spot and camping out (metaphorically speaking, of course) until you capture the shot.

In my view, however, the Lake Tanuki Diamond Fuji has become too well-known. Tour buses disgorge hordes of hopeful photographers coming from all over Japan and beyond for their Diamond Fuji shot, keeping the crowd-shy veteran photographers away.

Lake Yamanaka, on the other hand, offers lots of different viewing points, meaning that the period during which sunset diamond can be captured lasts much longer than Lake Tanuki’s sunrise diamond. Five months, in fact, from October until February of the following year. With more viewing spots and a longer period, there isn’t the same pressure to stake your claim and jealously guard your spot until you capture your shot!

Weather is the main issue with photographing the Diamond Fuji from Lake Yamanaka, as it can be difficult to get the right conditions in winter. This is because, even on clear mid-winter days, clouds frequently form in the late afternoon, just when you’re trying to get your photo. And as you can imagine, even with perfect conditions, the sun descends so rapidly that it’s pretty difficult to capture the moment when the sun hits apex of the mountain. Nonetheless, the fact that the sun is visible in the sky gives you the chance to track its trajectory and work out the best spot from which to take the photo. Although, this is easier said than done.

Choosing Lenses

Another factor to consider is choice of lens. It goes without saying that the better the lens, the better the photo, but were you aware that the actual structure of your lens aperture determines how many rays will emanate from the sun in your photo? When shooting with a small aperture to capture the sun flare, the number of rays visible in your photo depends on how many aperture blades your lens has. However, this isn’t quite as straightforward as it might sound. If your lens has an even number of blades, then your sun flare will produce exactly that number of rays, while an odd number of blades produces twice as many rays as blades in the lens aperture. For example, if your aperture array has eight blades (an even number), the sun will appear to have eight rays, while five blades (an odd number) will produce ten rays.

If you do have a choice of lenses to take with you, the aperture assembly is definitely worth considering, depending on your desired starburst effect.