Nagano Prefecture is full of scenic old roads, each steeped in history and legend. In this series, we visit these paths and share the stories they hold. This time, we explore the Kiso Road, a section of the old Nakasendō highway, one of the Edo period’s five major highways, which has preserved much of its original charm. Houses line the streets along this green mountain route, while weathered stone statues and roadside deities stand quietly in the villages and fields. Once gruelling mountain passes for travellers are now refreshing hiking routes, rich with history and natural beauty.

Text and Photos : Yūji Fujinuma / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Nakasendo / Narai-Juku / Woodcraft / Rural Japan / Hiking / History / Travel / Nagano Prefecture / Shinano / Lacquerware

Feudal Domains Station Border Officials to Tighten Surveillance

During the Edo period, with the aim of seizing control of the valley’s abundant forestry resources, the entire Kiso Valley came under the control of the Owari Domain—one of the three branch families of the Tokugawa shogunate. The authority of the Owari Domain extended north as far as Sakurazawa in what is now the southwestern part of Shiojiri City. At the edge of the settlement, a bridge spanning a tributary of the Narai River was designated as the boundary with the Matsumoto Domain. Based on that decision, posts were erected on either side of the bridge to mark the respective territories, with the east side controlled by the Matsumoto Domain and the west by the Owari Domain.

Centuries later, in 1940, local volunteers erected a stone monument on the western bank of the Narai River, on the Owari side of the border. With an inscription that translates as “From Here South, the Kiso Road,” this spot has since come to be widely recognized as the northern gateway to the Kisoji.

Motoyama-Juku, the 32nd Post Town from Edo

The northern end of the Kiso Mountain Range branches out further north beyond this monument, reaching the southern edge of the Matsumoto Plain. Approaching from Edo, this area marks the point where the road enters the Kiso mountains. At the spot where the plain gives out and the climb begins lies Motoyama-juku, a post town established in 1614 when the old route from Shimosuwa through Ono and Sakurazawa was abandoned in favor of the new path over the Shiojiri Pass.

The Matsumoto Domain came to regard this spot near the domain border as the northern gateway to the Kisoji, and established an inspection checkpoint for controlling the movement of cargo.

Motoyama-juku, the 32nd post town from Edo, stretched 582 meters from north to south. It had a principal inn (honjin) reserved for top officials such as feudal lords and powerful government officials, and an auxiliary inn (waki-honjin) for slightly lower-ranking officials. In addition, there were 34 ordinary inns (hatago) for common travellers and merchants. In this mountainous area with little arable land, many of the local villagers made their living by serving travellers or working in the mountains. One of Motoyama-juku’s claims to fame is as the birthplace of soba noodles, which feature frequently in historical records. These records describe how soba noodles originated in Motoyama-juku and became widely celebrated across the country, with “soba restaurant signs lining the highway.” Motoyama soba was even presented as gifts for feudal lords.

Today, since the opening of a station slightly to the south in Hideshio on the Chūō Main Line shifted the flow of travellers, Motoyama has lost much of its former bustle. The post town itself is now quiet, with few people in sight. But this only serves to strengthen the atmosphere of bygone days: along both sides of the street, traditional two-storey wooden houses with projecting upper floors and full “senbon-kōshi” latticework line the road, inviting visitors to relive the journeys of long ago.

On closer inspection, you notice that the buildings, which are all adjoining, are not aligned in a straight line along the street. Instead, each house is angled slightly relative to the street, so that one corner of the facade touches the road while the other is set back, forming a sawtooth pattern along the row. From the perspective of someone passing by, these recesses create blind spots, and also shelter. In castle towns, such spaces were often used to conceal ambushes, and it seems likely that a similar defensive purpose was intended here as well.

Heading to Niekawa-Juku

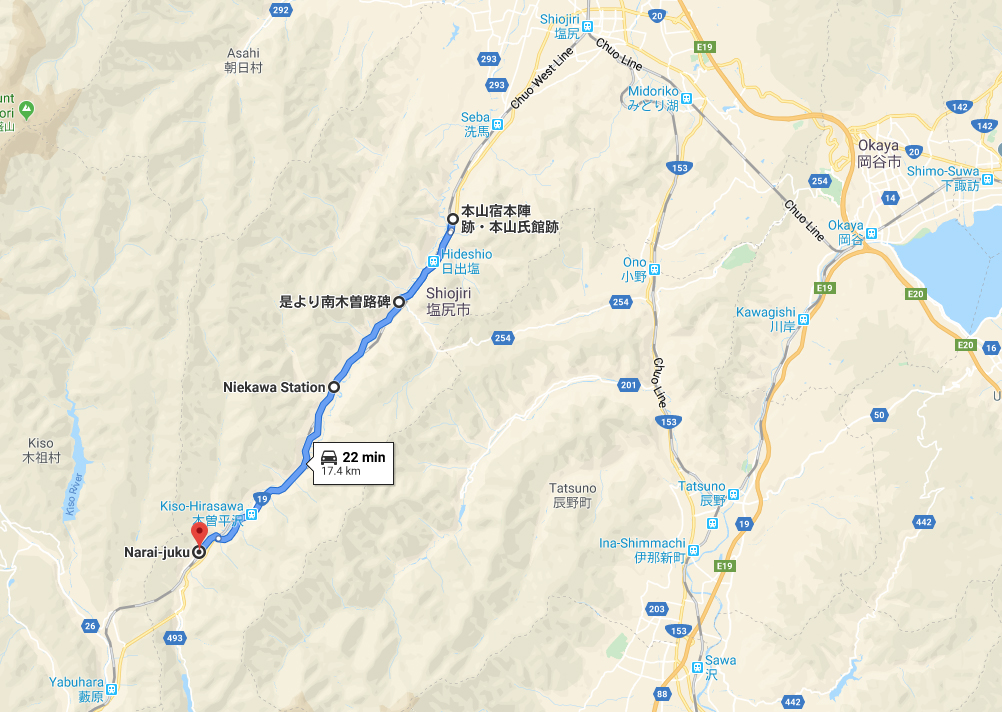

Continuing south, following the route past the Kiso Road monument, you come to Niekawa-juku. The eleven post towns from Niekawa to Magome are known collectively as the “Eleven Kiso Stations”, each of which once had its own honjin and waki-honjin principal and secondary inns for hosting travelling feudal lords and officials. From this point, the road plunges ever deeper into the heart of the Kiso Valley. During the Edo period, Niekawa boasted twenty-five hatago (traveller’s inns), but repeated fires destroyed the townscape. Today, only the reconstructed Niekawa Checkpoint at the northern entrance remains to evoke the days of old.

The checkpoint served as the northern guard post of the Owari Domain, inspecting travellers and monitoring the removal of domain-controlled products such as Kiso hinoki (cypress). A building with a gently sloping shingle roof weighted down by stones, houses the Kiso Archaeological Museum, which exhibits artifacts unearthed from the surrounding area.

Hirasawa, the Kiso Lacquerware Village with Folk-Craft Style Streetscape

Between Niekawa-juku and Narai-juku lies the Hirasawa district, which in the Edo period served as an ainoshuku, a “midway post station”, between the two. At the same time, Hirasawa prospered as a craft town known for hinoki cypress woodwork and lacquerware. Lacquerware techniques were first brought from Kiso-Fukushima and flourished in Narai, but Hirasawa eventually became the main production centre. In the Meiji era, artisans there devised a multiple-coating technique that spurred a remarkable growth in demand. In 1975, Kiso lacquerware was designated a Traditional Craft of Japan and, even today, about 80 percent of Hirasawa’s residents are engaged in lacquer-related work. The townscape stretches roughly 850 meters north to south, with lacquerware shops lining both sides of the street for its entire length.

The present streetscape took shape after a great fire in 1749. The curved road created fire-fighting, traffic-flow, and visibility problems so the Owari domain required that new buildings be set back, leaving about a one-metre space between each structure and the street. As a result, some sections developed an unevenness with the building facades lining up in a zig-zag arrangement that gives the street scenery a sense of depth and adds visual interest.

Each house is arranged with the main building facing the road, and behind it, along a passageway, lies an inner courtyard and a nurigura (lacquer-work storehouse) used as a workshop. The nurigura is a solid, thick-walled earthen storehouse type of building that keeps humidity and temperature constant and shuts out ultraviolet light and dust. Its upper floor serves as a drying room.

Facing the street, true to its reputation as a crafts town, each shop shows careful attention to detail. Even the signs and entrances feature inventive touches that lend the street a distinctive folk-craft charm. At the northern end of the street stands the Kiso Lacquerware Museum, which exhibits celebrated works and materials related to production, while the Kiso Kurashi no Kōgeikan (“Kiso Lifestyle Craft Hall”) displays and sells lacquerware and other wooden crafts. Every year in early June the area bustles with activity when around 200 lacquerware stores get together to put on the Kiso Shikki (Lacquerware) Festival. In 2006, the district—separate from Narai-juku—was designated as the Shiojiri City Kiso-Hirasawa Important Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings.

Narai-Juku. Premier Post Town of the Route: a Village of Woodcraft Sustained by Rich Forestry Resources

The distance from the outskirts of the Hirasawa settlement to Narai-juku is just under two kilometers, or about thirty minutes on foot. In the past, this town was known as “Narai Senken” (Narai of a Thousand Houses) and was the liveliest of the eleven post towns on the Kiso Road. Because the national highway was diverted around the outside of the old post town, the streetscape has remained intact to this day, giving visitors the otherworldly feeling of stepping straight back into the Edo period.

According to records from the mid-1800s, the closing years of the Edo period, Narai-juku had 409 houses, the largest number among the 26 post towns of the Shinano Province section of the Nakasendō, and a total population of 2,155, second only to Agematsu among the eleven Kiso post towns. The post-town trade catering to travellers flourished, but the town also prospered through local industries that made use of its rich forestry resources, such as mage-mono (bentwood ware), sashimono (joinery and fine cabinetmaking), and lacquerware production.

The townscape stretches for about one kilometre north to south along the Narai River. At both ends, masugata (defensive entrances that require travellers to make a series of 90 degree turns) were built to block a direct approach by intruders. The town is divided into three districts: Shimomachi (Lower Town), Nakamachi (Middle Town), and Kanmachi (Upper Town). Most buildings date from the late Edo period (early- to mid-1800s) and are of the dashibari-zukuri style, where the upper floor is cantilevered out above the street, sheltering the entranceway and providing more space upstairs. These buildings are narrow at the street front but extend deep to the rear. A typical house plan places the omoya (main residence) facing the street, followed by a small inner courtyard and then attached wings or dozō (earthen-walled storehouses). The main house is usually two stories high, with a tōridoma (earthen-floored passage) running along one side of the ground floor and three to four rooms opening off it. The attached wings to the rear are typically two to three storeys tall. Though the façades may look narrow from the street, the interiors are surprisingly spacious.

A distinctive feature of the buildings at Narai-juku is the “saru-gashira no yoroi-bisashi” (“monkey-head armored eave”), the construction style used for the timber awnings that extend above the ground-floor frontages. These “armored eaves” are made by overlapping four to five wide planks running along the façade to form the overhang. To keep the overlapped planks from slipping, a series of timber brackets sit on top of the overhang, with notches on the underside holding the planks firmly in place. As there are no posts supporting these overhangs, the awnings are tied into and suspended from the upper-floor posts with metal rods.

The term “monkey head” comes from the carving on the lower end of the vertical posts, which is shaped to resemble the head or face of a monkey. This kind of detail in a private house is rare even along the Nakasendo and is unique to Narai-juku.

Shimomachi, the lower town on the northern side, was once a district of craftsmen engaged in lacquerware production. Rows of narrow-fronted buildings line the relatively narrow street, many of which still operate as lacquerware shops.

■ The Townscape: Cultural Heritage Maintained Through Residents’ Persistent Efforts

After a short walk, the street widens as you enter Naka-machi, the central district. This was once the heart of the town, where the main and secondary inns for official travelers were located. Buildings such as the Tezuka family residence, which served as a wholesaler managing horses and riders for official use from the early Edo period, and the Hara family residence, which was used as a lodging house, have been preserved much as they were in the past.

The Tezuka family residence is open to the public as the Kamitoiya Museum, exhibiting historical documents and household items, while the Hara family residence houses a museum alongside its shop, also open to visitors.

The street then twists sharply—a 90-degree right turn, followed by a 90-degree left—into Kanmachi, the upper district. This section was once home to lacquered-comb craftspeople. The Nakamura residence, belonging to the industry’s founder, is now open to visitors. As a comb wholesaler, the house retains classic Narai-style features, including the armor-style eaves. It was almost moved to the Japan Open-Air Folk House Museum in Kawasaki, but a local campaign preserved this important heritage building in its original location.

In 1978, this former post town was designated an Important Preservation District for Groups of Traditional Buildings, encompassing almost the whole town. Residents established rules for preservation based on this designation, with various standards focused on ensuring that any renovations or new constructions harmonize with the traditional streetscape. Residents also take care to keep the town beautiful: in the early morning they can be seen sweeping the streets, and the six communal drinking-water fountains are carefully maintained, always running full and clear.

The roughly one-kilometre stretch of traditional streets ends at the Miyanosawa water fountain, beside which a restored official notice board (kōsatsuba) stands. Beyond the street’s final turn, Shizume Shrine, Narai’s guardian shrine, stands within a copse of Japanese cedar trees. The shrine was relocated here in the late 1500s. Located within the shrine grounds, the Narakawa History and Folklore Museum displays items used in the post town as well as local folk materials. Past the shrine, the climb toward Torii Pass begins, leading to Yabuhara-juku.