After long years of civil unrest in Japan, a unique gardening culture developed during the political stability of the Edo Period (1603-1868), initially led by the members of the samurai class, and quickly taken up by enthusiastic commoners. When Japan ended its self-imposed isolation in the mid-nineteenth century, the world was amazed by the gardens of Edo and the horticultural advances made by Japanese plant breeders, both amateur and professional.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Edo Period / History / Samurai / Tokyo / Japanese Gardens / Horticulture / flowers

A love of flowers that dates back over a thousand years

Japan’s oldest historical records, the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) and the Nihon-shoki (Chronicles of Japan) make frequent mention of plants, albeit mostly those with a practical use such as grain crops and timber trees. However, occasional mention of cherry blossoms and camellias indicates that the Japanese custom of admiring plants for their beauty alone was already well established.

The appreciation of plants for their aesthetics becomes more obvious with the Man’yō-shū poetry anthology which dates back to 759, in which a significant number of poems reflect on the merits of various plants and flowers. By the Heian Period (794-1185), interest in flowers was even greater.

The Heian Period is when the chrysanthemum, not mentioned in the Man’yō-shū, makes its debut at official ceremonies. It is thought that the chrysanthemum became the imperial family coat of arms during the Kamakura Period (1185-1333) after the retired Emperor Go-Toba used it as a crest on his garments. This is also when container gardening in the form of bonsai became widespread and people become ‘gardeners’, cultivating flowering plants and trees for pleasure.

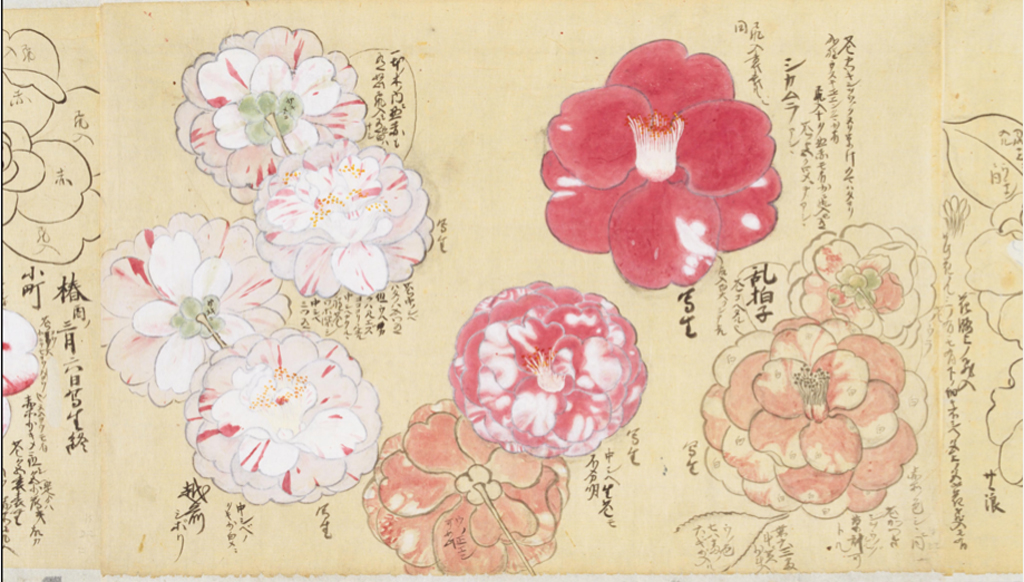

Japanese gardening shrugged off its Chinese influence during the Muromachi Period (1336-1573) and began to blaze a new, independent path. Hanami (flower viewing) excursions were already a popular pastime, and this is when large numbers of new and improved camellia and flowering cherry varieties appeared. Large scale events such as Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s lavish Daigo-no-hanami cherry blossom viewing extravaganza at Daigo-ji Temple in Kyōto also began to take place in the late Muromachi Period.

The Samurai – Edo Period Gardening Pioneers

In terms of gardening for pleasure in Edo (old Tōkyō), Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu was the first to get the ball rolling. Despite his reputation for being a somewhat unsophisticated man, Ieyasu was very fond of flowers, as was his son, the second shōgun, Hidetada. The third shōgun, Iemitsu, surpassed both his father and grandfather in his passion for gardening. All three were particularly ardent fans of the camellia.

With the ruling family so enamoured of gardening, many daimyō (feudal lords) felt that it would be prudent to follow suit. Their estates in Edo were soon transformed into veritable farms, with vegetables and medicinal plants grown alongside ornamental plants and flowers. Not only did the daimyō present flowers to the Tokugawa family as gifts, the ruling family also bestowed gifts of potted plants and seedlings upon their retainers. Allowing these plants to die would have caused great offense to the shōgun, which added considerably to the burden of those tasked with keeping them alive!

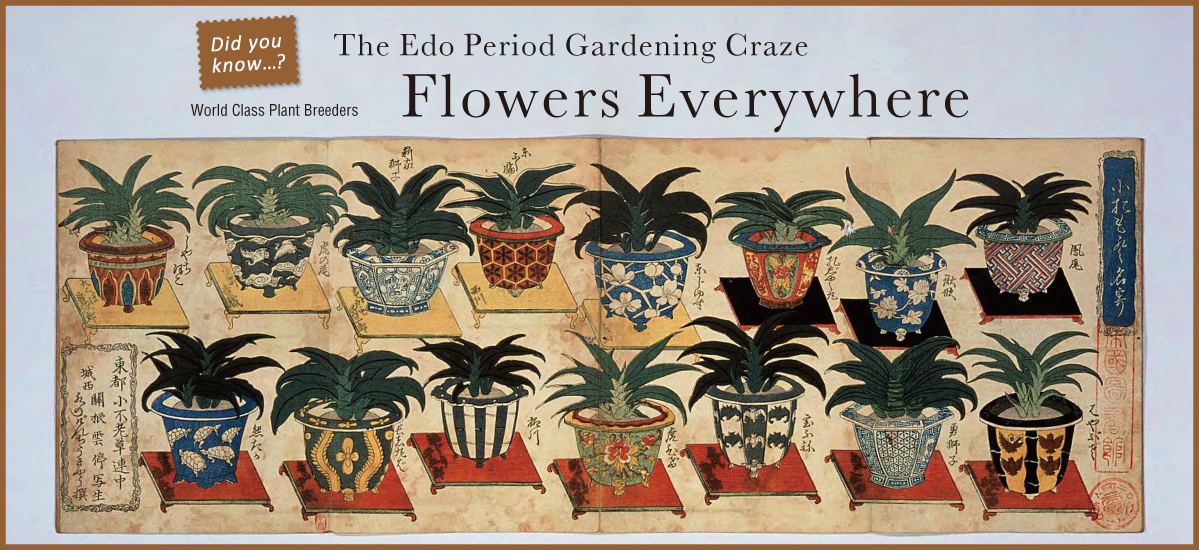

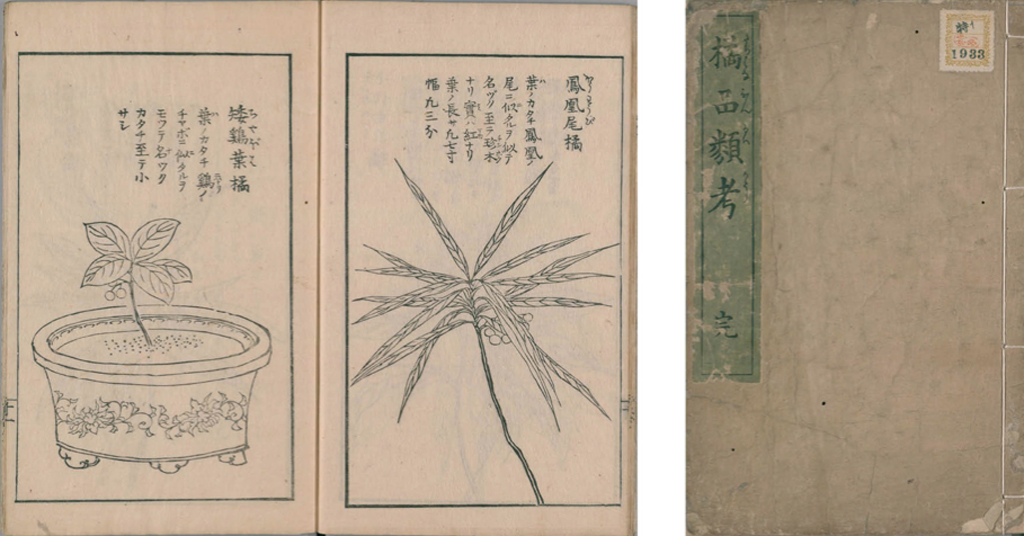

As gardening mania spread, some daimyō, proud of the varieties they had amassed, had coloured illustrations of their plant collections published. Others became obsessed with rare curiosities such as plants with variegated leaf colouring.

Next to catch the gardening bug were the lower-ranked samurai, followed by the wealthy merchant class, until eventually even the lowliest working-class tenement houses in Edo’s cramped back alleys had rows of potted plants lined up on the street under the eaves. The sight and sound of plant and flower vendors, their baskets of wares balanced on poles over their shoulders, became commonplace across the city.

The pursuit of gardening as a hobby in samurai society was not limited just to Edo. The sankin-kōtai system, which sought to control the daimyō by requiring them to reside in Edo in alternate years, had the effect of spreading Edo’s gardening culture throughout the country as the daimyō took the habit back with them to the provinces.

Edo Gardening Mania Fuels Horticultural Innovation

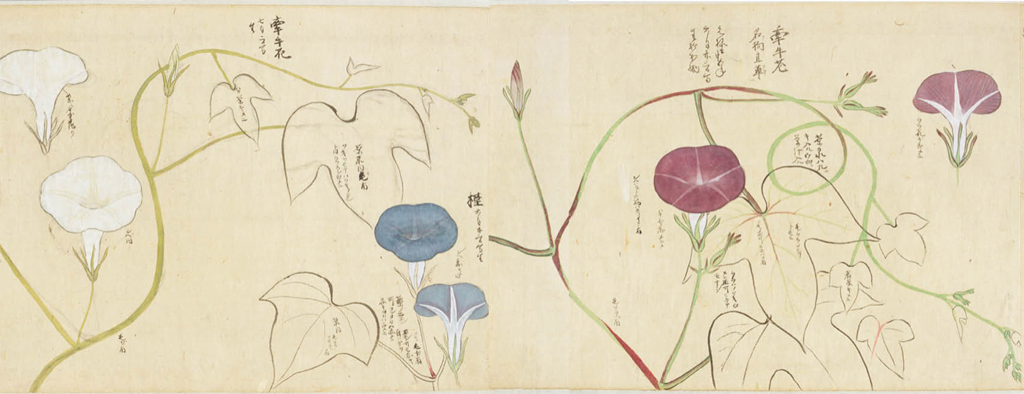

As the gardening craze spread, enthusiasts became increasingly focused on botanical novelties such as plants with unusual flowers and colour variegations, or dwarf varieties and trees with twisting growth habits. This passion for the unusual prompted rapid advances in propagation techniques such as grafting, root division and the taking of cuttings, as well as selective breeding. Even before Mendel developed his laws of genetics, experience and intuition led Edo plantsmen to use the same selective breeding techniques that Mendel experimented with, to deliberately induce plant mutations, including seedless varieties of morning glory (Ipomoea nil).

These new discoveries in plant breeding were accompanied by a flurry of publications, from simple illustrated growers’ manuals, to treatises on plant classification, and exquisitely illustrated reference books. The demand for such publications was strong, continuing unabated through the political unrest of the final years of the Edo period and the eventual overthrow of the shogunate government.

Plant Competitions and Competition for Plants

Gardening in Edo became a competitive endeavour. Plant aficionados gathered in public to enter their blooms in the ever-popular flower shows and competitions, and a ranking system similar to that used in sumō wrestling was even established. The gardening world of old Edo was extraordinarily egalitarian, with no class or social barriers to participation in competitions, and entries judged solely on the basis of their merits.

At the same time, however, novelty plants such as potted tachibana bushes (Citrus tachibana), whisk ferns (Psilotum nudum) and the sacred lily (Rhodea japonica), collectively known as kane-no-naru-ki (money-bearing trees) for their golden fruit, began to be traded for unbelievable prices. As demand outstripped supply, the threat of an overheated horticultural bubble economy loomed. As a result, the sale of these plants became subject to control under the shogunate government’s sumptuary laws that attempted to regulate luxury consumption.

A Gardening Culture Like no Other

The gardening craze stimulated new enterprises, giving the people of Edo plenty of choice as to where they could purchase their gardening needs. Ordinary folk bought their plants from wandering peddlers or from stalls at temple and shrine festivals. The asagao-ichi morning glory markets and hōzuki-ichi Chinese lantern plant (Physalis alkekengi) markets that sprung up around temples and shrines were another popular plant source.

During the mid to late 1700s, garden shops in the neighbourhoods of Sugamo and Komagome began printing pamphlets to advertise their businesses. Plant nurseries became leisure time destinations much like today’s shopping malls, and had all the hustle and bustle of trade fairs.

Common people who had no space for gardens of their own could still enjoy hanami (flower viewing excursions). Guidebooks featuring Edo’s best locations to appreciate the beauty of nature and gardens had something for every season, from early spring plum blossoms to autumn leaves.

The scale of the Edo Period gardening craze, which extended from the lofty ruling classes to the lowliest commoners, was unparalleled anywhere else in the world. When the first visitors from the West began to arrive after 1853, they were amazed at what they saw. Scottish plant collector, Robert Fortune, who visited Edo in the 1860s, was struck by the number and variety of potted plants he saw lined up on the streets outside people’s houses all over the city. Reflecting on the state of his own country, he commented that if a love of plants could measure the level of a civilisation, then Japan’s would be far superior!