The Shikoku Henro, a sacred pilgrimage around the entire circumference of Shikoku, encompassing all four prefectures of the island. Shikoku is thought to be where the Buddhist monk Kōbō Daishi (known during his lifetime as Kūkai) undertook ascetic training as a young man. The faithful forge their way over the craggy mountains and along the windswept coastal paths of the pilgrimage route, comforted in the knowledge that they are accompanied by Kōbo Daishi as he guides them towards peace and enlightenment.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photos : 谷口哲 Akira Taniguchi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Kōyasan / Pilgrimage / Henro / Kōbō Daishi / 88 Temple Pilgrimage / Shikoku

Journeying Alongside Kōbō Daishi, Japan’s Best-Loved Buddhist Monk

The Origins of the Henro – Kōbō Daishi’s Buddhist Faith and Ascetic Training

With as many as three hundred different pilgrimage routes in Japan, why is it that the sacred sites of Shikoku attract so many pilgrims? What inspires them to undertake such a punishing journey, bypassing the routes closer to home to walk the Shikoku Henro? Totalling some 1400 kilometres in length, the Henro takes a gruelling forty to sixty days to complete – even longer when weather conditions make the route more difficult.

The origins of the Shikoku 88 temple pilgrimage are the stuff of legend. Some believe that Kōbō Daishi walked the route during his religious training. Or perhaps Emon Saburō, a wealthy man from Iyo Province, travelled the circuit looking for Kōbō Daishi, seeking to apologise for refusing to help him. Another story holds that after Daishi’s death, leading disciple Shinsei retraced the route that Daishi had taken. Whatever the truth of the matter, all we have to go on are legends and folklore.

Buddhist monk, Kūkai, posthumously named Kōbō Daishi, was born in Shikoku in 774, in present day Kagawa Prefecture. Seeking advancement in the civil service, Daishi went to the capital in Nagaoka-kyō at the age of fifteen, where he studied Confucianism. However, increasingly dissatisfied with this life, he returned to Shikoku when he was nineteen, continuing his pursuit of knowledge in sacred places such as Tairyūgadake in Awa Province, as well as Muronosaki in Tosa Province and Mt Ishizuchi in Iyo Province.

It was during this time of ascetic training that Daishi resolved to devote his life to Buddhism. This is where he began extolling the virtues of Buddhism over Confucianism or Daoism. At the age of thirty-one, to deepen his understanding of esoteric Buddhism, he joined a mission to T’ang China, where he spent two years. Today, Daishi is known not only as the visionary founder of the Shingon sect of Buddhism, but also as a poet, calligrapher and civil engineer.

The Edo Period Guidebook that Popularised the Henro

The name “Henro”, which refers both to the pilgrimage route and to the pilgrims themselves, dates back many hundreds of years. Long ago, lands far from the capital were known as “hechi” or “henro”. Eventually henro came to signify the practice of walking in procession while chanting, although the term now refers only to the Shikoku pilgrimage. The faith that this pilgrimage represents is a combination of the ancient worship of natural features such as mountains and rivers, bizarrely shaped rocks and trees, with the Daishi faith that grew up around the legendary aspects of Kōbō Daishi, who is believed to protect and guide people towards enlightenment.

Shikoku 1300 years ago was a wild and remote land, parts of which were the exclusive domain of monks and their ascetic training. These aspects of Shikoku are mentioned in the Konjaku Monogatari-shū and Ryōjin Hishō anthologies, both compiled in the Heian Period (794 – 1185). Heian Period poet Saigyō is recorded as having gone to Shikoku on pilgrimage in 1167, as did the Kamakura Period itinerant Buddhist preacher, Ippen Shōnin. However, at that time the 88 Sacred Sites had not yet been linked into a single circuit and the Henro route as such did not yet exist.

Heading off on pilgrimage had become relatively popular among ordinary folk by the Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573), and it was between this time and the early Edo Period (1603 – 1868) that the 88 Sacred Sites route was established. From this point on, the Shikoku pilgrimage grew in popularity, spurred on by the guidebook, “Shikoku Henro Michi Shirube” (“Guide to the Roads of the Shikoku Henro”), written by the monk Yūben Shinnen in 1687. Yūben’s guidebook was innovative in that it assigned numbers to the pilgrimage temples and also included information on places to stay. The book was reprinted several times. Shinnen’s numbering system remains more or less the same today and is thanks to his book the temples are now often referred to by number, instead of by their actual names.

Local Goodwill Sustains the Poor and the Lame

The Shikoku Henro was once perceived as a rather bleak and dismal pilgrimage, far removed from the splendour of the Kansai region’s Saigoku Kannon Pilgrimage, or the pleasant tranquillity of the Chichibu Pilgrimage in Saitama, which people went on to fulfil their worldly desires through the practice of Buddhism. In contrast, those who undertook the Shikoku Henro were those burdened by misfortune – people suffering from incurable diseases; people in dire poverty, unable to feed themselves, or people seeking redemption from past misdeeds. Counting on the compassion of Kōbō Daishi, these unfortunate souls would set off into the wilds of Shikoku.

For a time there were even some known as “professional pilgrims”, people who had for whatever reason been driven from their home towns. Unable to return, they were forced to live out their lives on constant pilgrimage, relying on the charity of the local people. Not surprisingly, a lot more people died on the Shikoku Henro than on any of Japan’s other pilgrimage routes.

Those days are now long gone and today the numbers of young pilgrims and visitors from overseas are on the rise. The way that people approach the pilgrimage has also changed, with many now travelling the route by bicycle or motorcycle.

What hasn’t changed is the custom of “o-settai”, the local charitable tradition of offering aid in various forms to support the pilgrims. The charitable giving that enabled the poor of days gone by to make the pilgrimage continues, with offers of food and drink, perhaps a bed for the night, and sometimes even money. While this charitable tradition does also exist along pilgrimage routes in other regions, o-settai is a courtesy that is especially close to the hearts of the locals along the route of the Henro pilgrimage.

The Final Sacred Site of the Henro – Kōbō Daishi’s Eternal Resting Place on Kōyasan

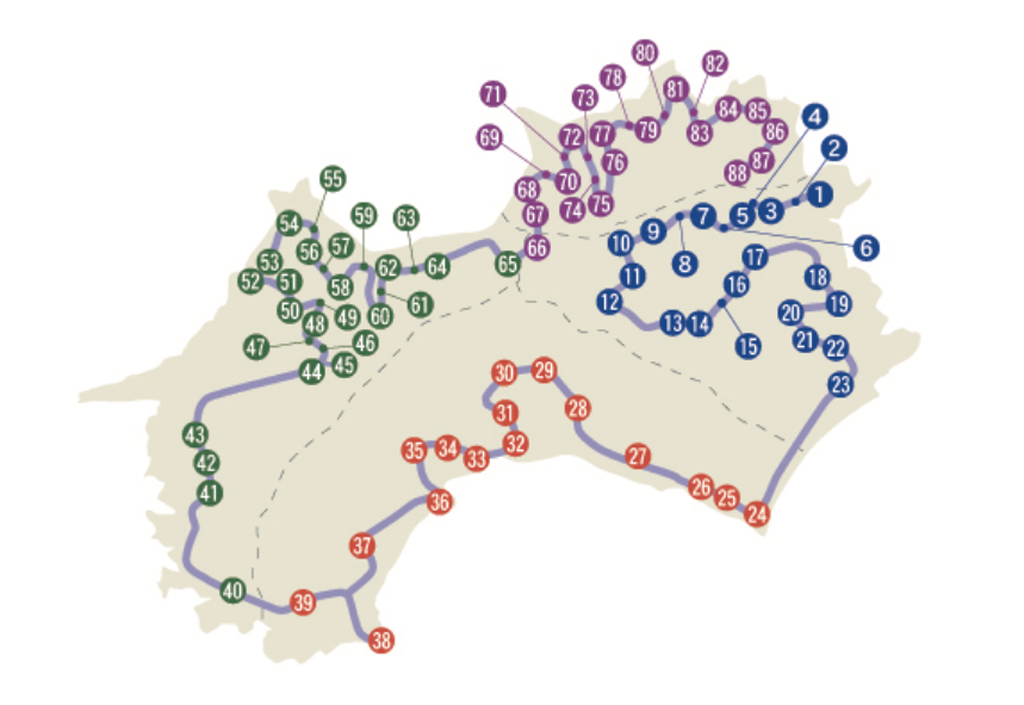

The long trip around the four prefectures of Shikoku usually begins at temple number one in old Awa Province (Tokushima Prefecture) and proceeds through Tosa (Kōchi Prefecture) and Iyo (Ehime Prefecture), before finishing up at the 88th temple in Sanuki (Kagawa Prefecture). Traveling to each sacred site in order is known as jun-uchi, while going in the reverse order is called gyaku-uchi. Gyaku-uchi is said to have originated with Emon Saburō, who set off around the island in a counter-clockwise direction during his desperate search for Daishi. The legend goes that Daishi appeared to Saburō who lay dying at the roadside. Saburō received forgiveness and pledged to restore one of Shikoku’s temples in his next life. For this reason, the gyaku-henro is said to be doubly lucky.

These days Awa is considered the place of Daishi’s spiritual awakening, Tosa as the place of ascetic training, where Daishi reached satori, Iyo as the place of enlightenment, and Sanuki the place of Nirvana. After completing the 88 temple circuit, it is customary to return to the first temple in Awa to offer prayers. The Henro is then completed once the pilgrim has been to pray at Kōbō Daishi’s mausoleum, Oku-no-In, on Mount Kōya in Wakayama Prefecture.

Kōbō Daishi died in 835, at the age of 62. He vowed upon his death to accompany the bodhisattva Maitreya, who is prophesied to return to Earth as the successor to the Buddha. Until then, Kōbō Daishi is believed to reside in eternal meditation at Oku-no-In on Mt Kōya, travelling the Shikoku Henro alongside pilgrims as he guides them through hardship and towards enlightenment.

The 88 Sacred Sites of Shikoku