In November 2018, ten festivals in eight prefectures from Tōhoku in the north of Japan to Okinawa in the south were officially added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list under the title “Raihō-shin, ritual visits of deities in masks and costumes”. Raihō-shin are bizarre-looking deities who come to drive off evil spirits, ward off disaster and herald good fortune and an abundant harvest. The ten rituals that have been inscribed on the UNESCO list are all ancient folk beliefs and religious concepts that continue to be observed today. Similar beliefs are found in all over the world.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Yuza no Amahage / Noto no Amamehagi / Mishima no Kasedori / Koshikijima no Toshidon / Japan World Heritage / Satsuma Iōjima no Mendon / Intangible Cultural Heritage / Akusekijima no Boze / Festivals / Miyakojima no Pāntu / UNESCO / Oga no Namahage / Yoshihama no Suneka / Yonekawa no Mizukaburi

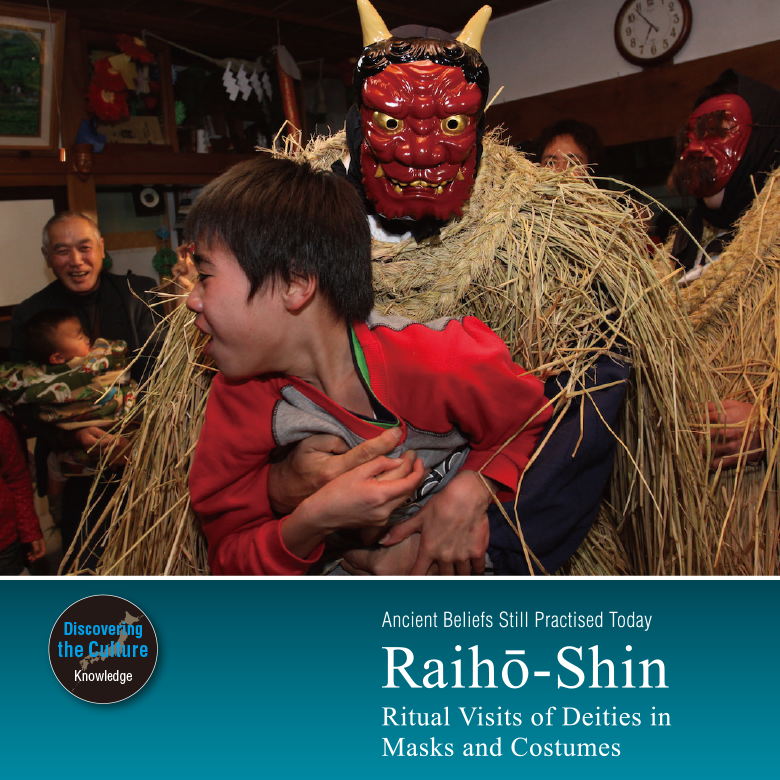

1. Oga no Namahage (Oga City, Akita Prefecture)

Where young men in terrifying costumes burst into houses and threaten children.

On the night of New Year’s Eve, when everyone is safe inside with their doors shut firmly against the gently falling snow, a ferocious gang of Namahage ogres is unleashed on an unsuspecting village. Wearing masks and heavy capes woven from straw and seaweed, and armed with sticks and cardboard knives, these bands of five or six Namahage have been chosen from young unmarried men of the village. Roaring like monsters, they burst into each house. “This year there will be bumper harvests and plentiful fishing!” they declare. Then, as they begin searching the room, they yell, “Any naughty kids here?” The visit is absolutely terrifying for the young children. However, the target of their threats are not only children, but any new family members such as young brides who need to be kept in line(!). In accordance with traditional etiquette, the head of the household entertains the visitors with mochi rice cakes and other refreshments.

Legend has it that the ancient Han emperor brought five ogres with him when he visited the Oga Peninsula. These ogres were treated harshly and made to work hard, but on one night of the year, New Year’s Eve, they were allowed to run amok. Nobody is entirely sure where the name, “Namahage” came from. One theory is that the word is a combination of namomi and hagu. During the long cold winter, people who get lazy and sit by the fire all day long, get patchy spots, or namomi, on their legs from the heat of the fire. Perhaps the Namahage come to tear off (hagu) these fire spots.

(Photo Credit: Teiji Morii)

2. Yoshihama no Suneka (Ōfunato City, Iwate Prefecture)

Divine messengers herald a bumper harvest and threaten to kidnap children.

On the night of January 15th, just as winter’s cold begins to intensify, creatures armed with short swords and wearing bizarre masks set off into the village. Dressed in capes of straw or animal skin, with long boots on their feet and bundles of abalone shells swinging from their waists, the Suneka visit each house in turn. On their backs they carry large straw bales with children’s shoes dangling from them. The straw bales symbolise a bumper harvest, and the abalone shells abundant fishing. More sinister though, the shoes dangling from the bales are said to be all that remains of naughty children they have abducted.

The Suneka jangle their abalone shells and pound on the door before bursting into the house roaring like wild beasts. To the waiting family gathered in the living room, they yell “Any lazybones, cry-babies or naughty kids here?”, then chase the terrified children around the room. In response, the head of the household offers mochi rice cakes and sweets to make them go away.

While the Suneka might be bizarre and mysterious beings, they are believed to be divine messengers bringing news of abundant crops and plentiful fishing. The name, Suneka has been handed down through the ages but the origin of the word is thought to refer to picking the ‘fire spots’ off the legs of people who have been lazily sitting by the fire all winter. The masks are generally made by the wearers themselves, so each one is unique. There’s a great deal of interest every year to see what kind of masks the Suneka will be wearing when they arrive.

(Photos courtesy of the Ōfunato City Board of Education)

3. Yonekawa no Mizukaburi (Tome City, Miyagi Prefecture)

Men in straw Mizukaburi costumes march around the neighbourhood. Straw from these costumes becomes protective talismans for the houses.

Every February, on the first “Day of the Horse”, a fire prevention ritual takes place. Just as they have for generations, men gather first thing in the morning at the Mizukaburi-juku (Mizukaburi lodge). There, they strip down to their underwear and wrap sacred straw shimenawa cords around their waists and shoulders. Over their heads and bodies they put a straw costume, known as an atama, that each one has created. With straw waraji sandals on their feet and their faces smeared with soot from a traditional cooking stove (the sign of the god of fire), they are ready to go.

With their Mizukaburi costumes on and transformed into Raihō-shin deities, the men first make for the Akiba Shrine in the grounds of Daiji Temple where they pray for protection against fire. They then head out to make their rounds of the houses, each of which has a bucket of water placed in front of it. As the costumed men splash the water over the roof of each house, the residents pull straw from their costumes and place it up on the roof as a talisman to protect the home against fire. Separate from this group, two masked individuals make their way through the village. One is clad head to toe in black priest’s garb to represent the fire god and the other, dressed as a woman, balances a pole over her shoulder with buckets at each end. They ring a bell as they walk, calling in at each home to collect offerings. These two are also considered Raihō-shin, bringing good fortune with them.

The origins of the Mizukaburi Festival are unclear but it is thought that it may have begun as a form of religious training for monks from the town’s Daiji Temple, which was built in the latter half of the 12th century. Only men from the Itsuka-machi district of Yonekawa in Tome City can take on the Mizukaburi role. Those who have reached the age of 60 and those for whom it is an inauspicious year, walk ahead of the group carrying bonten (poles with pompom-like arrangements at the top) to ward off misfortune.

(Photo courtesy of the Tome City Tourism Association)

4. Yuza no Amahage (Yuza-machi, Yamagata Prefecture)

Young men in straw capes burst into houses. Mochi is exchanged to ward off evil spirits.

Yuza no Amahage is held in three villages, Takinoura, Mega and Torizaki, on the nights of January 1st, 3rd and 6th, respectively. The ritual is similar to Oga no Namahage (#1, above). The Amahage wear special masks depicting ogres or elderly men and heavy capes called kendan, made of layers of straw. On their feet, they wear tabi socks with straw sandals or wooden geta. After visiting the local shrine, they set off into the village.

This Raihō-shin is conducted in various ways, depending on the village. In Takinoura, the Amahage proceed through the village without speaking, accompanied by the beating of drums and the ringing of bells. Only the Amahage enter the house. Once inside they stamp their feet loudly, put the mochi that has been set out for them into their chest “pockets”, threaten the children and young wives, rub the backs or shoulders of the elderly, then finally leave when they hear the drum signal from outside.

In Mega, the Amahage enter the house decorously and begin by offering a prayer at the family altar. After exchanging New Year’s greetings with the head of the household, their manner suddenly changes. They begin to shake, chasing the children with strange, high-pitched roars. Then, at the signal of the drum, they quieten down again. The young wife of the household offers sake and two cakes of mochi. The Amahage take one cake of mochi each, leaving the other behind for good luck.

In Torizaki, the Amahage arrive at each house accompanied by drumming, bell ringing and musical instruments. There, they greet the eldest resident and are offered sake and two cakes of mochi. As in Mega, they take one and leave one behind at the first house. However, from the second house onwards, they take both and leave behind one of the pieces they brought from the previous house.

Amahage differ from Namahage in that they don’t carry knives or sticks and they exchange mochi for good luck. In all three villages, straw debris from the costumes is regarded as sacred and is placed on the family altar as a talisman.

(Photo courtesy of the Yuza-machi Board of Education)

5. Noto no Amamehagi (Noto-chō, Wajima City, Ishikawa Prefecture)

Men and women in masks burst into homes to scare idlers.

The Amamehagi ritual used to take place in every part of the Noto region, but is now confined to parts of just Wajima City and Noto-chō. In this region, the ‘fire spots’ that people would get on their legs if they spent all their time sitting inside by the fire are called “amame” – a sure sign of a lazybones! Both young men and women take on the role of Amamehagi ogres who, it was said, would come and tear these amame off the legs of any idle slackers. Each neighbourhood conducts the ritual slightly differently, but in every place the ritual is carried out with dignity.

In Wajima the ritual takes place on the nights of January 6th, 14th and 20th. Upon arriving at each house, the Amamehagi first of all say a prayer at the family’s Shintō altar. That done, they begin to stalk about the room brandishing cardboard carving knives and sickles. Some of the female Amamehagi speak quite softly, but even so, the sight of the fearsome masks is enough to make the small children start wailing in fear.

In Noto-chō the ritual takes place on the night of February 3rd. Wearing homemade demon masks, straw capes and boots, children march through the streets striking bamboo pipes with their cardboard knives. As they go, they shout “Amame!”, in a bid to chase the lazy out to work. Each household greets them at the entrance with sweets or coins. Since Amamehagi takes place here on the same night as the Setsubun ritual, some families use this chance to do their mame-maki at the same time.

Amamehagi are also known locally as “Omoyō”, likening these visiting ogres to the grumpy-faced local officials who, in the past, had to go from house to house at the end of winter to shake the farmers out of their winter-induced torpor and get them back to work. Once the Amamehagi ritual has been conducted, people can be reassured that the long-awaited spring will finally come.

(Photo Credit: Teiji Morii)

6. Mishima no Kasedori (Saga City, Saga Prefecture)

Men in Kasedori costumes beat green bamboo poles on the floor to cast demons from the house.

Mishima no Kasedori takes place every year on the second Saturday in February, in the Mishima district east of Saga City. This is a ritual to pray for a plentiful harvest, and peace and prosperity in the household. The Kasedori are messengers of the gods in the shape of male and female birds. Two young men from the village are chosen to dress up. White cloths tied under their chins cover their heads entirely, leaving just their faces showing. They wear straw capes, mitten-like coverings on their hands and forearms, gaiters and tabi socks. With them they carry green bamboo poles that have been split lengthwise into sections at one end.

The event begins with a ceremony at the Kumano-gongen Shrine, followed by a procession from house to house, the Kasedori dragging their bamboo poles in silence. A lantern-bearer guides the Kasedori through the dark streets. Behind them comes one person with a Tengu goblin mask and another with a basket containing an old-fashioned account book. When they come to each house, the lantern-bearer announces their arrival to the head of the household. Once all the family is assembled, the Kasedori run into the house, first the male followed by the female. Inside, they beat their bamboo poles vigorously againt the floor to chase out any demons. At the appropriate time, their hosts serve sake or tea. In recent times the ritual has become simplified and is often performed just inside the entrance of the home.

Kasedori started in the mid-17th century when local people, concerned about the spread of an epidemic, invited the Kishū Kumano deity to protect the populace. The epidemic subsided and the ritual has continued ever since, in the hope of receiving continued protection.

(Photo courtesy of the Saga City Board of Education)

7. Koshikijima no Toshidon (Satsumasendai City, Kagoshima Prefecture)

Men in outlandish Toshidon costumes go from house to house bestowing blessings upon children.

The word, Toshidon, refers to the god of the New Year, who is said to come down from the heavens, or from the top of high mountains, riding a headless horse. On the night of December 31st, bizarre-looking Toshidon bestow blessings upon children. The ritual formerly took place throughout the Koshiki-jima islands but is now performed just on Shimokoshiki Island, the largest of the group.

The costume is a cape made from sago palm leaves and the hairy bark of the windmill palm, worn over a black cloak. Sharp, foot-long noses protrude from the centre of oversized red or blue masks, the monstrous faces split from ear to ear by enormous mouths. These menacing Toshidon look as if they might grab a child at any moment. When they arrive at a houses with children between the ages of three and eight years old, they make a noise to mimic the sound of a galloping horse coming to a halt, shouting “Oru ka? Oru ka? To wo akeyo!” (“Anyone here? Anyone here? Open the door!”) The children nervously open the door and usher these apparitions into the home. The Toshidon encourage and praise the children for their accomplishments, and point out where they could do better. The children promise to be good and then get on all fours so that the Toshidon can place a large cake of Toshidon-mochi on their backs.

The origins of the ritual are unknown. It has been conducted since before the Meiji Period as part of the children’s education and upbringing. It could possibly have begun an agricultural ritual – at a time when rice was a precious commodity, the Toshidon-mochi rice cakes may have symbolised parents’ wishes for their precious children to grow up strong and healthy. Once the Toshidon leave, the people of the island can look forward to a safe and happy new year.

(Photo courtesy of the Kagoshima Prefecture Office of Education Cultural Assets Section)

8. Satsuma Iōjima no Mendon (Mishima-mura, Kagoshima Prefecture)

To drive out evil, folk in Mendon costumes caper about, hitting people with leafy sprigs and creating a nuisance.

Masked Mendon deities appear as part of the Hassaku Taiko Odori festival, which is dedicated to the Kumano Shrine. They caper around bumping into the drummers and hitting onlookers with a leafy sprigs from a tree, to drive out evil spirits. The mask, which is formed from an upside-down bamboo basket, is worn over the entire head and shoulders. Fourteen-year-old children make the masks, layering and pasting paper onto the outside of the baskets and attaching cardboard eyes, noses and eyebrows, as well as huge ears, decorated in red and black spiral patterns. A single horn protruding from the forehead gives the mask a suitably ogre-like expression.

The ones who actually dress up as Mendon are men between the ages of 25 and 34, who are not participating in the drum dance. They wear straw capes and gloves to ensure that nobody can tell who they are. On the day, they wait near the shrine building. At first, one jumps out and circles the dancers three times. The rest of the Mendon then appear one after another and start teasing onlookers, chasing them and hitting them with the leafy tips of branches. The Mendon are believed to have special authority and nobody is allowed to challenge them or to try and find out who is under the mask. Some of the Mendon are children. They chase onlookers around with bamboo and leafy sprigs. On the final day, at twilight, the Mendon lead a procession around the village rounding up evil spirits and driving them into the sea.

The origins of the festival are hazy, but one story goes that the drum dance and Mendon ritual began as a celebration of rewards given to three local men who served during Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s invasion of the Korean Peninsula in the 1590s.

(Photo courtesy of the Kagoshima Prefecture Office of Education Cultural Assets Section)

9. Akusekijima no Boze (Toshima-mura, Kagoshima Prefecture)

People dressed as Boze in outlandish masks and wielding sticks called boze-mara, drive evil spirits from homes.

Boze are deities in tall, outlandish masks that appear during bon-odori dancing on the island of Akuseki-jima. This takes place on the 16th day of the seventh month of Japan’s ancient calendar (which could be sometime in August or September, depending on the year). The Boze are smeared with red clay. As well as their masks, which measure up to a metre high, they wear skirts made from fan palm fronds. With their wrists and ankles wrapped in hairy windmill palm bark, they wield clay-covered sticks called a boze-mara. Onlookers smeared with the clay from this stick are said to have their demons expelled. Women will be blessed with children.

Three young men from the island are chosen to wear the Boze costume. On the afternoon of the festival, they wait near a sacred graveyard. They are summoned with a call from a village elder, accompanied by drumming. Upon this signal, they rush into the square where everyone is watching the bon dancing and start chasing the women and girls around. The drummer beats out another signal, and the Boze begin their whirling dance. At another drum signal they resume chasing the women and children, before returning to the graveyard. After that, the final duty of the Boze is to destroy the masks, leaving no trace. Meanwhile, with evil spirits safely banished for another year, everyone gathers at the community hall to enjoy a night of eating and drinking.

The spirits of the dead are said to return to their families during the bon period. One researcher has suggested that the Boze ritual serves to bring this period to a close by leading the community back to the world of the living, and guiding the spirits back to the afterlife. It is said that there used to be a belief locally that the spirits of the ancestors might be accompanied by evil spirits when they return to the island during at this time.

(Photo courtesy of the Kagoshima Prefecture Office of Education Cultural Assets Section)

10. Miyakojima no Pāntu (Miyakojima City, Okinawa Prefecture)

Goblins smear onlookers with mud to bring good fortune and ward off disaster.

Miyakojima’s Pāntu is currently held in two districts of the island, each enacting the ritual in quite different ways. The Pāntu are goblins or demons who, in the Shimajiri District, smear mud on people to ward off disaster and bring good fortune.

In the Shimajiri District Pantū visit on two auspicious days of the ninth month of Japan’s ancient calendar (which could be sometime between late September and early October, depending on the year). Three young men cover themselves in black mud and dress from head to toe in mud-soaked vines. And this is not just any mud; it gives off a foul smell that lingers for days. On the day of the event, after receiving prayers from shrine maidens at the local shrine they sally forth into the village, smearing mud over anybody they come across. New houses and cars are also protected by getting smeared with the mud. The event is thought to have originally started out with just one man running through the village wearing the mask of a visiting deity.

Currently, because sightseers who have come to view the event have complained about getting muddy, organisers are considering how to proceed in future.

In the Nubaru District, the event takes place on the Day of the Ox in the twelfth month of the ancient calendar (sometime between late December and February, depending on the year). Here, the ritual is generally enacted by women and school-aged boys – no mud is involved. At around five in the afternoon, a boy in a Pāntu mask leads a procession of people, some blowing conch shells and beating drums. Women wear wreaths of clematis on their heads, clematis sashes around their waists and carry leafy sprigs from the cinnamon tree to expel harmful spirits. As the procession moves, they shout “Hōi! Hōi!”. At each intersection they come to, they form a circle and shout “Uru uru uru!” to ward off evil. When they get to the edge of the village, the women remove their clematis wreaths and sashes. The festival quietly ends with a dance.

(Photos courtesy of Miyakojima City Board of Education)

UNESCO video introducing Raihō-shin. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1h_sykcyAI