Based on local ingredients born of a wide variety of geographical and climatic features, Japan’s regional fare is famous the world over and draws visitors to Japan from across the globe. And what better way to enjoy each region’s distinctive cuisine than with a glass of locally brewed sake! The past few decades have seen a huge revival of interest, both within Japan and internationally, in shōchū – a traditional distilled liquor. In the not-too-distant past, shōchū had the dubious honour in Japan of being thought of as cheap booze for middle-aged blokes – an image that has undergone a major rehabilitation in recent years. Shōchū has now been adopted as the trendy tipple of choice by the creative and the hip, best enjoyed with a dash of jazz in sophisticated surroundings.

Add a new dimension to your next shōchū experience by learning the basics about shōchū, how it’s made and the different regional varieties.

Text and Photos : 中島有里子 Yuriko Nakajima / Editorial Supervision : 小林昭二 Shoji Kobayashi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Kōji / Imojōchū / Mugi Shōchū / Kokutō Shōchū / Shōchū / Nihonshū / Japanese Sake / Awamori / Honkaku Shōchū

Let’s Talk Basics – Fermentation vs Distillation

Ever since the world discovered the joys of fermented fruits and grains thousands of years ago, humanity has enjoyed a mostly convivial relationship with alcohol. Human ingenuity has given rise to a multitude of varieties of liquor and countless types of mixed drinks or cocktails. But let’s first take a step back and talk about the most basic of liquor basics, the distinction between fermented and distilled liquors.

Simply put, fermented liquors, which have a lower alcohol content than distilled liquors, are produced by fermenting the sugars in fruits and grains to produce an alcoholic beverage. Well-known examples are wine (produced by fermenting the juice of grapes) and beer (produced by fermenting malted barley mash). Japanese sake (Nihonshū) is also a fermented liquor, produced by fermenting ingredients such as malted rice using a process more akin to brewing beer than to making wine.

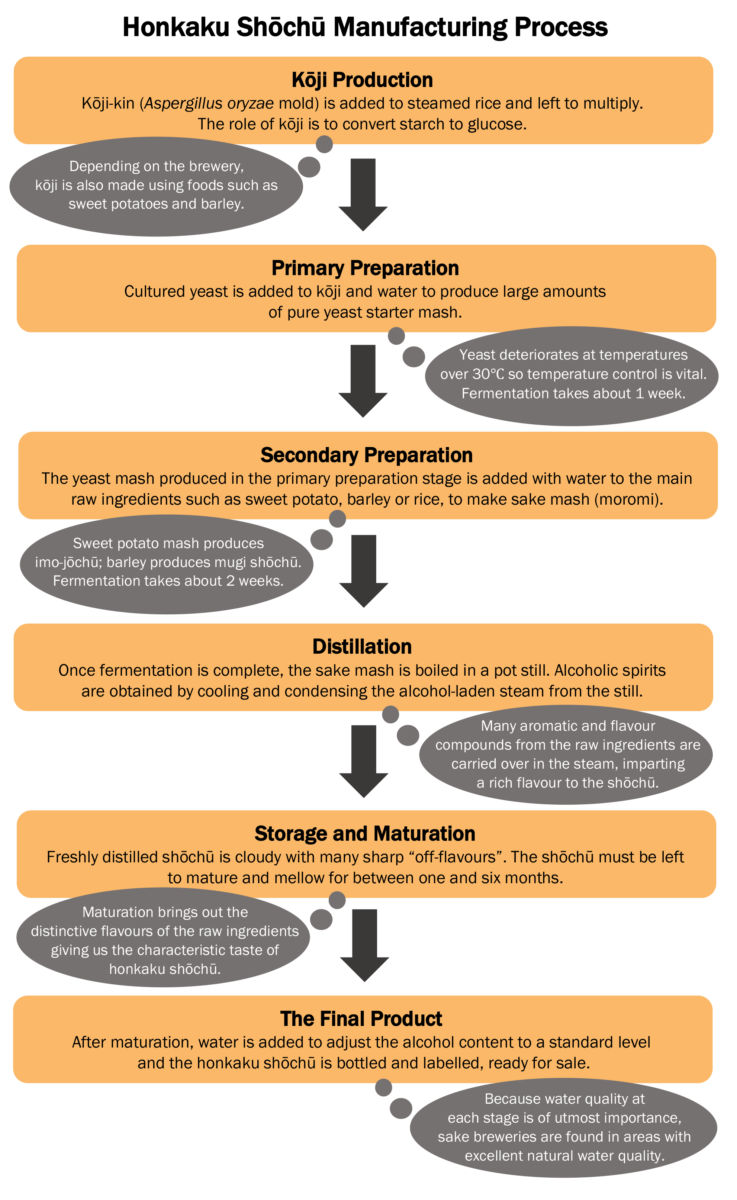

Distilled liquors, or spirits, are obtained by boiling fermented liquor mash inside a still so that the ethanol component (the alcohol) in the mash evaporates. As the alcohol-laden steam rises to the top of the still, it is channelled through cooling tubes and condensed back into liquid form. Because ethanol has a lower boiling point than the other liquids in the mash, it evaporates early in the distillation process. Although other components are also carried over in the steam (such as fragrance and flavour compounds and a certain percentage of water), distillation is stopped before all the liquid in the mash can evaporate, resulting in an extract with a much higher alcohol content than the original fermented mash. Using this distillation process, whisky is obtained from fermented barley mash; brandy from fermented grapes, and rum from fermented sugarcane juice. Similarly, shōchū is a distilled spirit obtained, depending on the shōchū variety, from a wide range of fermented ingredients such as rice, barley, sweet potato or sugar.

Honkaku Shōchū – What is it?

Shōchū can be divided into two types depending on the manufacturing process: singly distilled shōchū (tanshiki jōryū shōchū) and continuously/multiply distilled shōchū (renzokushiki jōryū shōchū).

A 1971 revision in the alcohol taxation law saw the official adoption of the term “honkaku shōchū” (authentic shōchū) to refer to authentic, singly distilled shōchū made according to traditional methods used for over five centuries. Another term used to refer to honkaku shōchū is “otsurui shōchū”. The spirit is obtained by using simple pot stills to distil single batches of fermented mash made from ingredients such as grains or sweet potatoes, mixed with kōji, yeast and water. The resulting liquor, whose alcohol content by volume must not be more than 45 percent, retains the flavour and aromatic characteristics of the original ingredients. Once referred to as “kyūshiki (primitive) shōchū”, singly distilled shōchū and its now prized traditional single distillation technique were once thought of as old-fashioned and outdated compared to modern, industrial-scale distillation.

Of course, single batch distillation was the only method available to produce shōchū until the introduction of British industrial distillation technology in the late 1800s. This technology, which relies on a continuous stream of fermented liquid being fed into the stills and produces a constant stream of distilled alcohol out the other end, enabled the extremely cheap production of vast amounts of high purity alcohol. The shōchū that results from this industrial-scale distillation is known as kōrui shōchū. Cheaply produced and commonly used for making mixed drinks and fruit liqueurs, kōrui shōchū is clear and colourless without any particular flavour idiosyncrasies. The law stipulates that the alcohol content of kōrui shōchū must be below 36 percent by volume.

Kōji – The Vital Ingredient

To produce alcohol, starches in the raw ingredients must first be converted into sugars, which are then fermented. In many parts of Asia, including Japan, kōji-kin (Aspergillus oryzae – kōji mould) is used to activate this process.

There are three types of kōji mould used in shōchū making: yellow kōji, black kōji and white kōji. Yellow kōji has long been used to brew Nihon-shū, miso, shōyu (soy sauce) and vinegar, although the fact that it doesn’t ferment well at warmer temperatures makes it unsuitable for use in tropical climates. In tropical Okinawa, black kōji is used to make the Okinawan liquor, awamori. The individual considered to be the father of modern shōchū is scientist and industrialist Kawachi Gen’ichirō, who was born in 1883 and grew up in his family’s miso and shōyu making business. In 1910, he succeeded in isolating and cultivating a variety of black kōji that came to be widely used in shōchū production.

Since black kōji produces large amounts of citric acid, it has the fortuitous ability to prevent sake mash (moromi) from spoiling during alcohol fermentation. Suited to sake brewing in hot regions, the adoption of black kōji dramatically improved the quality of shōchū. However, temperature management is difficult with black kōji and the black pigment from the rapidly reproducing spores could soon coat every surface of the brewery – a definite drawback! This issue has now been largely resolved with the development of newer strains that are more easily managed.

Kawachi Gen’ichirō later discovered white kōji, a mutation of black kōji. The use of white kōji, which is easily cultivated, fast acting and produces a mellow flavour, prompted immediate advancements in shōchū production in the Kyūshū region.

Honkaku Shōchū Varieties

The array of honkaku shōchū styles available is vast; each with its own subtle flavour and aromatic characteristics. Let’s take a look at some of the main regional varieties and what goes into them.

Imojōchū. Main ingredient – sweet potato (satsuma-imo)

The fragrant aroma and slight sweetness of the main raw ingredient, sweet potato, is characteristic of imojōchū. The most commonly used sweet potato variety for imojōchū is “Koganesengan”, which has a high starch content. Other sweet potato varieties used include Beni Satsuma and Beni Azuma.The main production areas for imojōchū are the prefectures of Kagoshima and Miyazaki in Kyūshū. Kagoshima’s Satsuma Shōchū, a sweet potato shōchū, is a protected geographical indication.

Mugi Shōchū. Main ingredient – barley (mugi)

As with many types of liquor, barley is the main raw ingredient in mugi shōchū. Mugi shōchū is believed to have originated on Iki Island in Nagasaki Prefecture, Kyūshū. Seven distilleries on Iki Island continue to make the traditional Iki shōchū, now a protected geographical indication, made with two parts barley to one part rice kōji. Other varieties of mugi shōchū are widely manufactured all over Kyūshū, with Oita Prefecture being the main production centre. Oita shōchū, which is currently enjoying a domestic boom, is an “all barley” shōchū, made using a barley kōji along with barley as the main raw ingredient

Kome Shōchū. Main ingredient – rice

Rice kōji is used as the fermentation starter for the majority of shōchū varieties, which then have ingredients such as sweet potato, barley or buckwheat as their main raw ingredient. Shōchū made with rice as the main raw ingredient, as well as rice kōji, is called kome shōchū (rice shōchū). A famous example of kome shōchū is Kuma Shōchū, a protected geographical indication from the Hitoyoshi region of Kumamoto Prefecture, Kyūshū.

Awamori. Main raw ingredient – long-grain rice

Awamori is the traditional shōchū of Okinawa. Black kōji mould is added to all of the rice that makes up the main raw ingredient, turning the whole lot into kome kōji. Unlike most shōchū, which goes through two fermentation processes, awamori is fermented only once. The other big difference is that awamori is made with long-grain indica rice, not the short-grain japonica rice usually used to make shōchū. Awamori that is aged three years or longer is called kūsu. Ryūkyū Awamori is a protected geographical indication restricted to Okinawa.

Kokutō Shōchū. Main raw ingredient – cane sugar

Kokutō shōchū is made only in the Amami Islands of Kagoshima Prefecture. The main raw ingredients are rice kōji and unrefined brown sugar made from sugarcane juice. The brown sugar imparts a characteristic sweet fragrance.

In addition to the varieties described above, shōchū can also be made with other raw ingredients, including buckwheat, beans, nuts, sesame and millet, and even with vegetables and herbs.

The labels on shōchū bottles carry a wealth of information, such as whether it is honkaku shōchū, and what the raw ingredients are and what type of kōji was used. With so many regional varieties and such a wide range of ingredients and characteristics, the world of shōchū offers much to explore. Kampai!