Every culture has its own “ghoulies and ghosties, long-leggedy beasties and things that go bump in the night”. In Japan, these mythical creatures, half seen and half imagined, lurking in the shadows and getting up to no good, are collectively known as yōkai. Sometimes comical but sometimes the stuff of nightmares, yōkai pop up in the most unexpected places!

Join leading yōkai scholar and collector Yumoto Kōichi in exploring, through his extensive collection, the weird and wonderful world of yōkai.

Text : 湯本豪一 Yumoto Kōichi / Cooperation : The Yumoto Kōichi Memorial Japan Yōkai Museum (Miyoshi Mononoke Museum) / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Yōkai Museum / Miyoshi Mononoke Museum / Welcome to the World of Yōkai Series / Hiroshima Prefecture / Yōkai / Yumoto Koichi / Night Parade of One Hundred Demons / Emaki / Miyoshi

Putting a Face to People’s Fears

Yōkai are thought to have emerged as an expression of people’s ambivalent feelings towards nature, their sense of disquiet and fear of what lurks in the shadows. They would have started out as old wives’ tales before being recorded in writing, and then in pictorial form, which has enabled us to visualise them all the more easily.

Numerous yōkai will have been forgotten about in this process, meaning that those we know about today are merely the tip of the yōkai iceberg. It’s no exaggeration to say that the paintings and drawings of yōkai that remain, the ones we’re able to enjoy through exhibitions and books, are truly precious.

Japan’s Oldest Confirmed Yōkai Scroll

Emaki (picture scrolls) are the oldest form of document relating to yōkai that remain to this day. The earliest of these is Hyakki Yagyō (Night Parade of a Hundred Demons), verified as having been painted during the Muromachi Period by Tosa Mitsunobu (lived 1434 – 1525), the founder of the Tosa school of painting. This scroll, a national important cultural property, is housed in the collection at Shinju-an, a sub-temple at Daitokuji Temple in Kyōto.

Although it’s not entirely accurate to call Daitokuji’s Hyakki Yagyō scroll the oldest depiction of yōkai, it is indeed the oldest to feature yōkai alone. While earlier depictions of yōkai do exist (for example Tsuchigumo, a giant demon spider, from the Tsuchigumo Sōshi scroll painted during the 1300s) the focus in such works is not on the yōkai themselves. The Tsuchigumo scroll tells the legend of how Minamoto no Yorimitsu (944 – 1021) slayed Tsuchigumo and features many human characters in addition to the demon spider. The purpose of this story is to expound on Yorimitsu’s heroism. The hapless Tsuchigumo was only ever a supporting character, a vehicle to demonstrate Yorimitsu’s prowess. The difference between this scroll and Tosa Mitsunobu’s work is that in the latter work there are no humans at all, only yōkai running rampant through the streets.

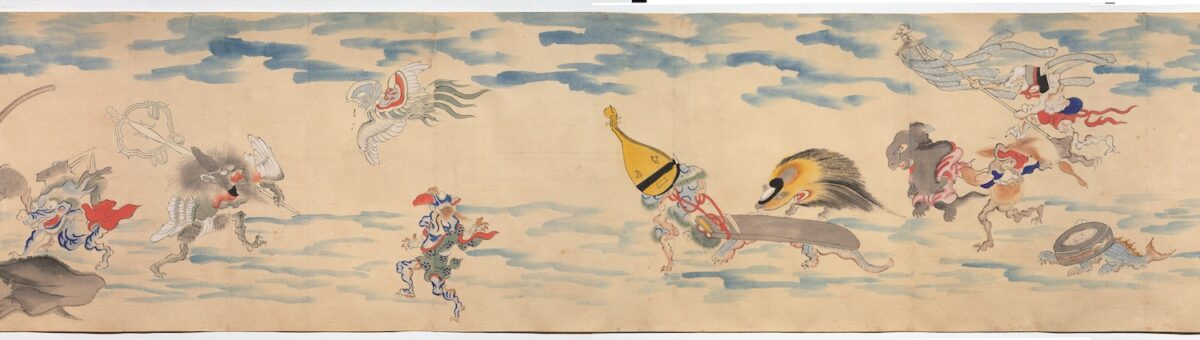

Tosa Mitsunobu’s scroll exerted a major influence over depictions of yōkai throughout the Edo Period, a time during which artists continued to paint the Night Parade of One Hundred Demons. Yōkai from the Tosa scroll later reappear in scrolls, woodblock prints and hanpon (books printed from woodblocks) during the centuries that followed, including in the scroll shown in the photo above.

Everyday Objects Acquire Souls After Years of Use

The scroll in the photo above was painted much later than Tosa Mitsunobu’s scroll in the Edo Period, but it’s interesting to note that this Edo Period scroll faithfully recreates all the yōkai from the Tosa scroll. Many of the yōkai depicted are actually everyday objects. This is based on an old belief that utsuwamono (containers, tools, and instruments) that have been used for many years acquire souls of their own. In the centre, a koto (Japanese harp) is depicted being pulled along by a biwa (Japanese lute). Walking alongside them is a creature that looks like a hedgehog with a shoe for a face – the shoe yōkai. Bringing up the rear are two Buddhist altar fittings that have taken the form of yōkai, waniguchi (literally “alligator mouth” – a disk-shaped gong) and hossu (a brush-like priest’s horsehair flapper).

It’s thought that the yōkai in the Night Parade of One Hundred Demons scrolls originated from the Tsukumogami-ki, a famous scroll that relates the story of what happens when everyday objects are thoughtlessly discarded. In the Tsukumogami scroll, tools and utensils that have been discarded during the traditional end-of-year cleaning harbour a deep sense of resentment at being thrown out into the streets. They hatch a plan to take their revenge on the human society that rejected them. Eventually though, the yōkai turn to Buddhism and depart this world in peace. Essentially, this tale is used as a context in which to demonstrate how thankful people ought to be for Buddhism, a great religion that can deliver even the souls of yōkai !

The Night Parade Assumes a Life of its Own

The fact that so many yōkai scrolls were painted means there are also many preliminary sketches remaining. These range from, for example, high quality artistic sketches by artists of the Tosa and Kanō schools to rather awkwardly-drawn images that were probably sketched by amateurs. As artists continued the tradition of painting the demons’ night parade, a range of variations emerged, with the order of the yōkai changing and new yōkai being added to the lineup. There are even scrolls titled Night Parade of One Hundred Demons that feature entirely different yōkai from those in the early scrolls. This sheer diversity has long continued to exercise the minds of yōkai scholars.

Yōkai Go Forth and Multiply

Even through the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912), while Japan was undergoing a rapid and purposeful programme of modernisation, yōkai continued to proliferate. As Japan began to embrace Western traditions, new objects such as jinrikisha (rickshaws), lamps and western-style umbrellas began turning up as yōkai. With so many domestic and everyday objects around to turn into yōkai, it’s little wonder that Japan’s yōkai population continued to increase.

Popular emaki such as the various Night Parade of One Hundred Demons scrolls show just how rich and fertile the yōkai world is, and provide a great entry point into this fascinating aspect of Japanese culture.

Cooperation

The Yumoto Kōichi Memorial Japan Yōkai Museum (Miyoshi Mononoke Museum)

Japan’s first yōkai museum, the Yumoto Kōichi Memorial Japan Yōkai Museum (Miyoshi Mononoke Museum) opened in April, 2019, in the city of Miyoshi, Hiroshima Prefecture. The museum houses and exhibits Yumoto Kōichi’s collection of over 5,000 pieces of yōkai art. The museum’s collection also includes the Ino Mononoke Roku (The Haunting of Ino Heitarō) scroll, an illustrated story about a series of hauntings that took place in the city of Miyoshi. In addition to curated exhibitions, the museum features interactive digital displays such as the “Digital Yōkai Encyclopedia” where visitors can find out about various yōkai at a touch, and the “Team Lab Yōkai Amusement Park” where visitors can colour in their own yōkai and watch their pictures move around the walls of the space and take on a life of their own.

Address: 1691-4 Miyoshimachi, Miyoshi City, Hiroshima Prefecture

Phone: 0824-69-0111