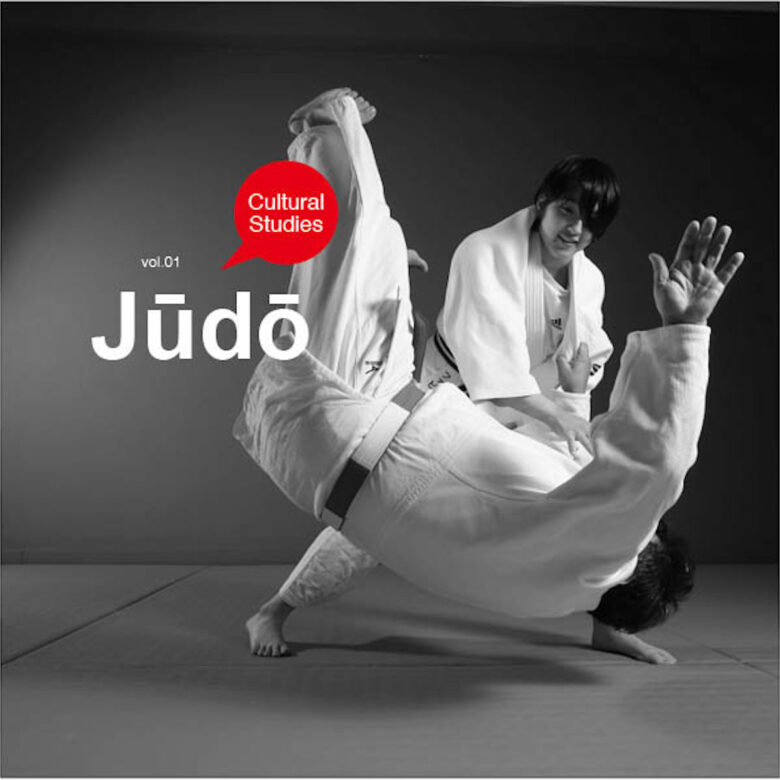

Jūdō has gained perhaps the most popularity worldwide of all Japan’s martial arts. The inaugural World Judo Championships were held in 1956, and jūdō became an official sport at the Tokyo Olympics in 1964 for male competitors, with the women’s program included at 1992 Barcelona Olympics. All this stemmed from the vision of one man, Jigorō Kanō. Manabi-Japan visited the Kōdōkan Jūdō Institute in Tokyo to learn more about this fascinating character and the discipline he founded.

Text : Sasaki Takashi / Photos : 平島 格 Kaku Hirashima / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Jūdō / Martial Arts / Jūjutsu / Kōdōkan / Cultural Studies Series

Jigorō Kanō and the Kōdōkan Jūdō Institute

Jūdō grew out of jūjutsu, a type of close combat for defeating an opponent either bare-handed or with a short weapon, and a much older Japanese martial art. It was Jigorō Kanō who developed the jūjutsu combat technique into jūdō, a dō (literally meaning ‘the way’). Born in the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate, Kanō devoted his life to education, sports and furthering international understanding.

Kanō began studying at Tokyo Imperial University (now Tokyo University) in 1882, and at the age of twenty-two, in a twelve-mat (roughly 20m²) room at Eishō-ji Temple in Taito Ku, Tokyo, he began teaching his own unique form of jūjutsu. This was the inception of what was to become known as ‘Kōdōkan Jūdō’.

There are now more than two hundred countries and regions affiliated with the International Judo Federation (IJF), and the martial art developed in a tiny room by Jigorō Kanō has been adopted by people all over the world. Kanō’s legacy remains strong though. In 1951, upon the establishment of the IJF, it was specifically stipulated that it observe the jūdō principles established by Jigorō Kanō.

So, how is jūdō different from jūjutsu?

<Jigorō Kanō>

1860: born in Hyōgo Prefecture. 1877: enters Tōkyō Imperial University. Studies philosophy, politics and economics; begins learning jūjutsu. 1822: founds Kōdōkan Jūdō. Starts teaching jūdō in a twelve-mat room in Tōkyō’s Eishōji Temple. 1893: becomes director of Tokyo Higher Normal School (present day Tsukuba University) and begins providing professional development for a large number of educators. 1909: becomes the first International Olympic Committee (IOC) member from an Asian country. 1911: establishes the Japan Amateur Sports Association (now called the Japan Sports Association) and becomes inaugural chairman. 1936: attends the Berlin IOC Session and successfully bids for the 1940 Tōkyō Olympics (later ceded to Helsinki and eventually suspended due to WWII).

In March 1938, returning to Japan after attending the IOC session in Cairo, Jigorō Kanō succumbed to pneumonia aboard the Hikawa Maru and died two days before the ship reached Yokohama. He was seventy-seven years old.

Cultivating mind and body for the good of society

We spoke to Motonari Sameshima, head of the Instruction and Education Department at the Kōdōkan Jūdō Institute. He explained that while Japan’s ancient martial art, jūjutsu, developed as a method of killing an enemy during battle, Jigorō Kanō, an educator first and foremost, developed Kōdōkan Jūdō for the purpose of human education. Mr Sameshima commented that although people watching Olympic jūdō television coverage might think jūdō is merely a contest of physical strength and skill, Kōdōkan Jūdō is quite a different thing altogether. The purpose of jūdō, he says, is not just to win competitions.

This is best expressed in two of Jigorō Kanō’s mottos, Seiryoku-zenyō (best use of energy) and Jita-kyōei (living prosperously together). These expressions can be interpreted in a variety of ways, but Mr Sameshima explains it simply as training both the mind and body through jūdō, and cooperating with others for the betterment of society.

The essentials of Jūdō

At the Kōdōkan, trainees of varying abilities train together.

Anybody, regardless of strength, can join in

We visited the Kōdōkan during one of the women’s training sessions, which take place every evening except Sundays. Among the participants, naturally enough, were serious black belt competitors with dan rankings, but there were also office workers who had taken up jūdō as a hobby, and mothers who wanted to try jūdō themselves after watching their children’s sessions. There were also women from outside Japan, who had come to train here at jūdō’s most ‘sacred site’. After warming up, trainees of all levels and backgrounds came together to practice uchikomi (technical drills) and randori (free sparring).

At the Kōdōkan, emphasis is placed on what they call the ‘three aspects of training’. Mr Sameshima explains that these three aspects involve training with ‘weaker opponents, stronger opponents, and matched opponents’. A weaker opponent allows a stronger opponent to take the lead, while the weaker opponent learns to handle someone stronger. Meanwhile, when opponents are evenly matched, both can improve. This practice of participants of varying levels training together is something that Mr Sameshima says is highly valued in Kōdōkan jūdō.

Learning jūdō begins with learning how to lose

As with many Japanese martial arts, jūdō can become a lifelong sport. While worries about injuries or lack of fitness may put some people off, as long as everybody maintains the principles, there is no need for undue concern. Trainees have taken up jūdō at the age of sixty-five, and a black belt second dan ranking was achieved by a woman in her seventies.

The first thing that beginners learn at the Kōdōkan is the art of falling safely.

“Practising how to fall is basically practising how to lose. It’s unusual, isn’t it, that a sport would start by teaching you how to lose!” Mr Sameshima laughs. “For example, at a tournament of one hundred people, there can only be one winner. That means there are ninety-nine losers! But you can learn an awful lot by losing, not just in jūdō, but in life in general.”

After training, one young woman had this to say:

“Before taking up jūdō, I’d tried all sorts of different exercise routines at gyms and sports clubs. But getting into the jūdō-gi (training wear) and rolling around on the tatami mats is way more fun than any of that. Plus, it really tones your body!”

Jūdō has come to be loved by people all over the world, regardless of gender or ethnicity, nationality or religion. And right now, in our stressful modern society, Jigorō Kanō’s Kōdōkan Jūdō, first and foremost a discipline to train and cultivate mind and body, becomes more relevant than ever.

Pictured right is Mr Motonari Sameshima, head of the Education and Instruction Department at the Kōdōkan, whom we interviewed for this article. On the left is Mr Sanshirō Yamamoto, head of the Grading Department, who helped us with the photography.

Kōdōkan Jūdō Institute

Address: Kasuga 1-16-30, Bunkyō Ku, Tōkyō 〒112-0003

Tel: (+81)3-3818-4172 (English) / 03-3811-7152 (Japanese)

Getting started with Kōdōkan Jūdō

The Kōdōkan is in Bunkyō Ku, Tōkyō. The dōjō is open from 4.00 p.m. until 8.00 p.m. Monday to Friday, and until 7.30 p.m. on Saturdays. Closed on Sundays. Members are free to train as they wish. There are a variety of courses to choose from, including general training sessions for those with experience, courses in the basics for beginners, and even sessions for pre-schoolers. The women-only programme runs Monday to Saturday from 6.00 p.m. to 7.30 p.m., in a dōjō on a separate floor.

Fees for randori sessions (experienced trainees only):

Membership ¥8,000

Membership card ¥500

Monthly fee ¥5,000 or ¥800 per day (no membership needed for casual visits)

Beginners pay an additional ¥1,000 to enrol in the school beginner classes, and ¥5,000 per month tuition fee. Trainees are required to wear Jūdō-gi – women add a plain white T-shirt under their top. A set of Jūdō-gi suitable for a beginner costs from around ¥10,000. Gear can be purchased at the kiosk just inside the entrance to the Kōdōkan.