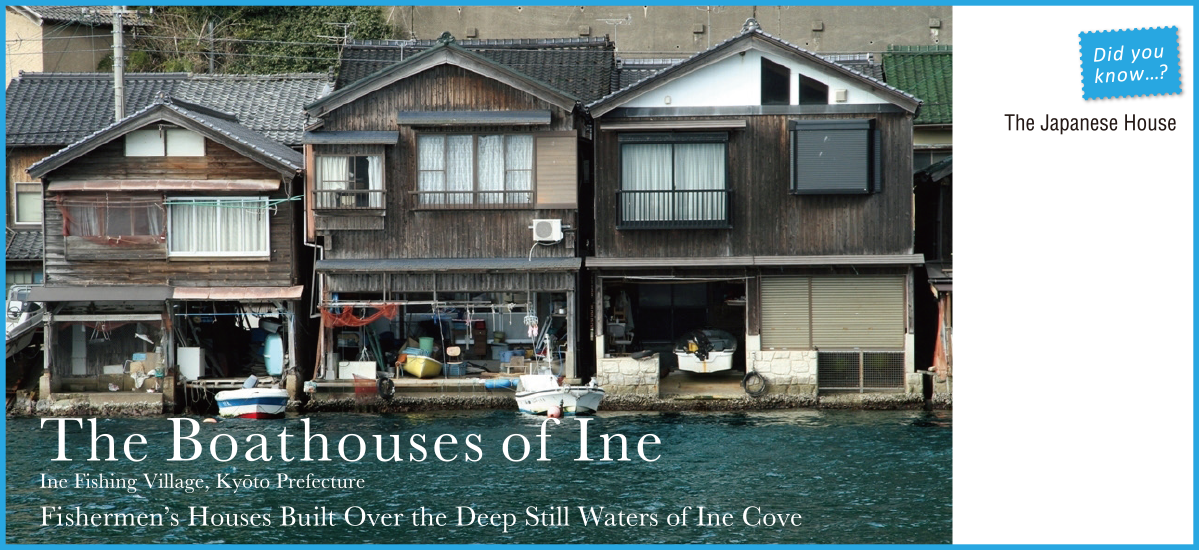

Over centuries, Japan’s homes have been continually refined and adapted to suit people’s ways of life and the hugely diverse climate and natural features encountered in various parts of this archipelago, which stretches three thousand kilometres in a sweeping arc from north to south. One such design that responds to the challenges and opportunities presented by a deep bay closely hemmed by mountains is the “Ine no Funaya”, or “Boathouses of Ine Cove”.

Text : Sasaki Takashi / Photos : 谷口哲 Akira Taniguchi / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Funaya / Boathouses / Wakasa Bay / Kyoto Prefecture / Fishing

Garages With Indoor-Outdoor Flow – Literally!

As an island nation surrounded by ocean, Japan has an extensive coastline dotted with fishing villages, but none quite like Ine, where two hundred and thirty “funaya” (boathouses) jostle for space at the edge of Ine Cove, a deep inlet in northern Kyōto Prefecture’s Wakasa Bay. While these appear to be fairly conventional houses when seen from the street, there’s one major difference. Instead of having an internal garage for the family car accessed from street level, these funaya open out to the bay so that the family fishing boat can be docked downstairs, below the living spaces. The entire lower level of each funaya is open to the sea and has a concrete or stone ramp allowing small fishing boats to be stored and easily launched from right under the house.

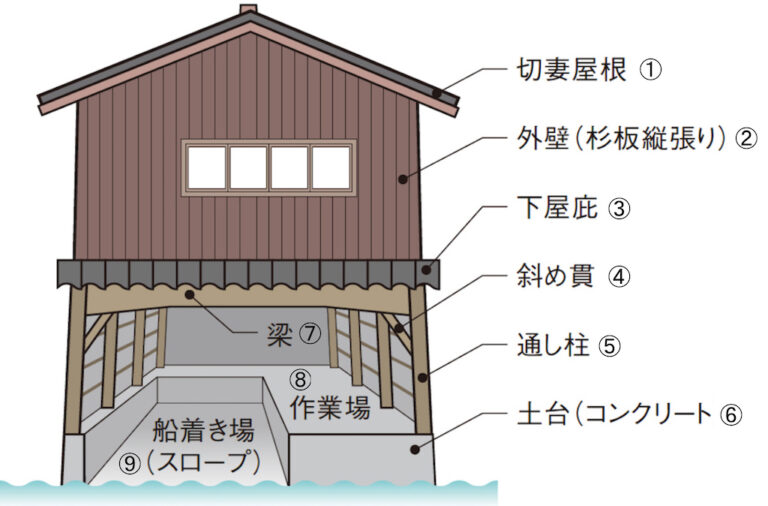

Front Elevation of a Typical Funaya (Seaward Side)

① Kirizuma yane – pitched roof; ② Soto kabe – exterior wall (cedar cladding); ③ Geya hisashi – downstairs canopy roof; ④ Naname-nuki – diagonal tie-beam; ⑤ Tōshi-bashira – continuous (2-storey) column; ⑥ Dodai – foundation (concrete); ⑦ Hari – crossbeam; ⑧ Sagyōba – workshop; ⑨ Funatsukiba – boat ramp

The boathouses of Ine developed as a response to the unique geography of Ine Cove. This deep-water cove sits inside a hook of land at the top of the Tango Peninsula, at the western mouth of north-facing Wakasa Bay. The entrance to the cove itself looks south into Wakasa Bay and is surrounded by steep mountains down to the water’s edge on all three sides. This offers the cove an unusual degree of protection from the Sea of Japan’s frequently harsh conditions. Additional shelter is provided by Aoshima Island, a small island at the mouth of the cove that serves as a breakwater. Conditions inside the cove are almost as calm as a lake, with very little wind to whip up the sea. The tidal range (the height difference between low and high tide) on the Sea of Japan coast is small compared to the Pacific coast, making it possible to build right down to the water’s edge here in Ine.

Setting off to sea from right under the house

“Funaya are a lot sturdier than they look,” says Hisao Katō, a fisherman for close to seven decades. Now in his eighties, Katō san still takes his boat out fishing every day. “They say these houses barely even shook in the big earthquake at the beginning of the Shōwa era,” he adds.

The earthquake that Katō san refers to is the 1927 Kita Tango Earthquake which severely affected the Tango Peninsula. This devastating event saw the deaths of up to three thousand people and the destruction of around ten thousand homes.

The funaya houses have a very simple structural skeleton, built without any interior columns on the lower level in order to allow space for the boats. Continuous timber columns known as tōshi-bashira form the exterior uprights, running from the foundation up through the upper level. Crossbeams tied to these form the joists of the upper floor. Exceedingly sturdy pine is used for the beams, while Castanopsis, a timber from the beech family that stands up well against seawater and salt-laden air, is used for columns and foundations. Rather than standing perfectly vertical, the columns of the exterior frame incline slightly inwards from base to top. Viewed from the gable ends, the houses have a slightly arrow-head shape, which enhances the overall strength of the structure.

In fact, a research team from Kyōto University has recently been investigating this unique construction method. Confirming Katō san’s reports of how the boathouses withstood the devastating Kita Tango Earthquake, the research suggests that this traditional construction method, handed down through the generations, is indeed extremely resistant to seismic force.

There’s another unique aspect to Ine’s traditional townscape. Fishing families here actually have two houses; one is the funaya at the water’s edge and the other is a slightly larger main house just across the narrow street that runs behind the boathouses. The funaya are generally places of work where boats are stored and maintained and where fishing gear is repaired, while the families live in the main houses across the road. However, as the family grows and teenagers begin craving their own space, older children will often end up sleeping across the street in the family’s funaya.

Katō san spent the early years of his marriage living in his family’s funaya and speaks with nostalgia about how life once was in Ine.

“In the olden days, when the successor to the family fishing business got married, he and his wife would live in the funaya at first. Eventually, as children came along and the grandparents retired, the young family would move into the main house while the grandparents would move across the road to enjoy their retirement by the sea. Although young people just leave home as soon as they get married nowadays, this is how we lived until not so long ago.”

Ine is often referred to as Japan’s most beautiful coastal village. Crafted not only by time and the forces of nature, the landscape here is a unique response to a particular environment on the part of people who have lived with the sea day in and day out for generations.

“Funaya no O-yado, Shio no Kaori” is a boathouse available for overnight accommodation. Bookings are limited to one group per night (up to ten people). The interior of the boathouse remains very much as it has always been. This is a place to just relax and get a feel for what it was once like to live in a funaya.

“Shio no Kaori” will be closed from 1 December 2020 until 28 February 2021, but details of other funaya accommodation are listed on the Ine Kankō

http://ine-kankou-jp.check-xserver.jp/wp/en/inns

This video provides a lovely overview of Ine Town, its funaya and harbour.