Minka are traditional Japanese residences constructed in a range of styles to suit their various geographical locations and the lifestyles of their inhabitants. Made from natural materials and built to last, these substantial buildings and the know-how that went into their construction have stood the test of time, withstanding ferocious storms and even earthquakes. In this article, let’s take a look at some of the basic elements that make up a traditional Japanese house.

Text : Sasaki Takashi / Illustrations : Aso Yuriko / English version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Japanese house / Minka / Irori / Japanese Roof Styles / Tokonoma / Fusuma / Shōji

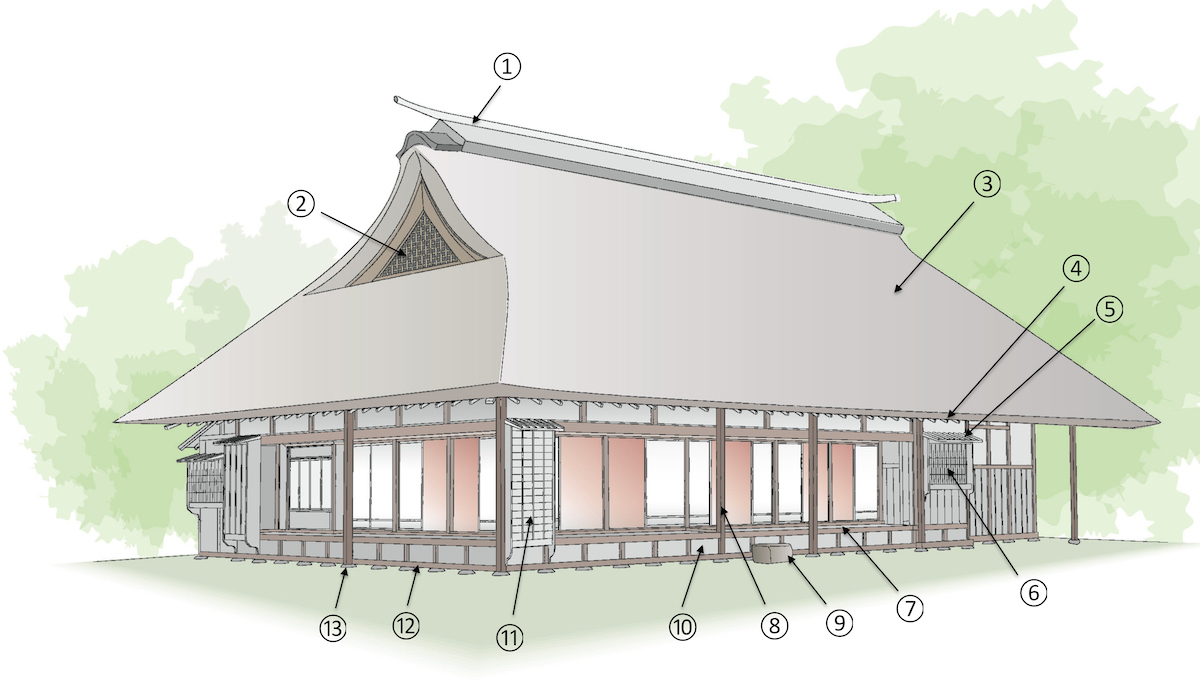

The Exterior Elements of a Traditional Japanese House

① Ōmune (大棟) – Main Ridge

The ōmune is the main ridge of the roof, the highest section of the house. It encloses the munegi, or ridge beam. Once the post and beam framework of the house is completed and the ridge beam finally put in place, a jōtōshiki or ridge beam-raising ceremony is held to bless the house and pray for its safety. This ceremony is also known as the mune-age or the tatemae.

② Hafu (破風) – Gables

The hafu are the triangular end panels or sections, including the gable end wall and barge boards, and any decorative plates on the gable wall surface. There are different names for various styles of hafu. Domed, bell-shaped gables are called kara-hafu (literally, Chinese cusped gable), while the triangular gables at the end of concave sloping roofs are called chidori-hafu because they resemble the downswept wings of a chidori (plover) bird in flight.

③ Kayabuki-yane (茅葺屋根) – Thatched Roof

Kaya is the general term for reeds and grasses used for making roofing thatch. Highly water-resistant stalks such as those of susuki grass (Miscanthus sinensis) and yoshi, the common reed (Phragmites australis), are used. The roof tiles commonly seen nowadays on traditional-style homes in Japan became common during the latter part of the eighteenth century. Other traditional roofing materials include timber shingles called kokera-buki, and hiwada-buki, shingles made from cypress bark.

④ Taruki (垂木) – Rafters

The taruki are the rafters that extend from the ridge beam down to the eaves of the roof. Shitaji is the name given to roof framing timbers such as purlins or battens fixed horizontally across the rafters, that the roof cladding is attached to.

⑤ Hisashi (庇) – Window and Door Eaves

Hisashi are additional eaves protruding over windows and entrances, constructed beneath the main roof to provide shade and protection from the rain. A roku-hisashi is a simple set of eaves cantilevered straight out from the wall, with a flat underside and slightly sloping upper side. The udegi (crossarm) hisashi has a more steeply sloping roof supported by crossarm braces.

⑥ Kōshi Mado (格子窓) – Latticed Window

Kōshi mado are windows with a lattice made from thin strips of wood arranged within a timber frame. Those consisting entirely of parallel strips, without any cross-pieces, are called renji. Because the provide effective security while allowing air and light to pass through, renji are used for sliding doors as well as windows. The lattice windows seen in the white plaster second-storey walls of Kyōto’s traditional machi-ya houses are known as mushiko-kabe.

⑦ Egawa (縁側) – Veranda

The engawa is an open, timber-floored corridor or veranda constructed around the outside of the house. A common characteristic of traditional Japanese houses, the engawa provides indoor-outdoor access to many of the rooms. Engawa without rain shutters or exterior panels to keep the rain out are called nure-en.

⑧ Enbashira(縁柱) – Veranda Posts

The en-bashira are the posts or pillars at the outer edge of the veranda that support the veranda eave purlin. Enbashira are also known as engawa-bashira.

⑨ Kutsu-nugi Ishi – Stepping Stone

A kutsu-nugi ishi is a stone step or slab placed in front of the engawa or inside the main entrance to the house. Footwear can be removed here and left on the step before entering the house.

⑩ En-no-Shita – Under-floor Space

The en-no-shita is a crawl space under the veranda or floor, created to provide ventilation and reduce humidity inside the house. Some are completely enclosed with baseboards to prevent dead leaves and debris from accumulating under the house, while others have gaps between the boards to improve airflow. This is a favourite place for cats and dogs to retreat from the heat of the day.

⑪ Tobukuro– Box for Rain Shutters

The tobukuro is a tall, closet-like storage space, usually at one end of the engawa or near the entrance of the house, for storing rain shutters and sliding doors when not in use.

⑫ Dodai (土台) – Foundation Sill or FootplateThe dodai is a system of horizontal beams that form the footplate at the base of a Japanese timber building. They are hewn from decay-resistant timber such as chestnut and laid directly atop the foundation stones, forming a base for the posts of the building. However, many of the important internal pillars of the building, such as the daikoku-bashira (main pillar) sit directly on the foundation stones rather than on the dodai.

⑬ Soseki (礎石) – Foundation StonesSoseki are the foundation stones of the building. To ensure stability, they are laid into a bed of stone or compacted gravel. In old minka, the footplate and pillars sat atop round, uncut foundation stones, while the daikoku-bashira (main pillar) was commonly placed atop a special square-hewn stone.

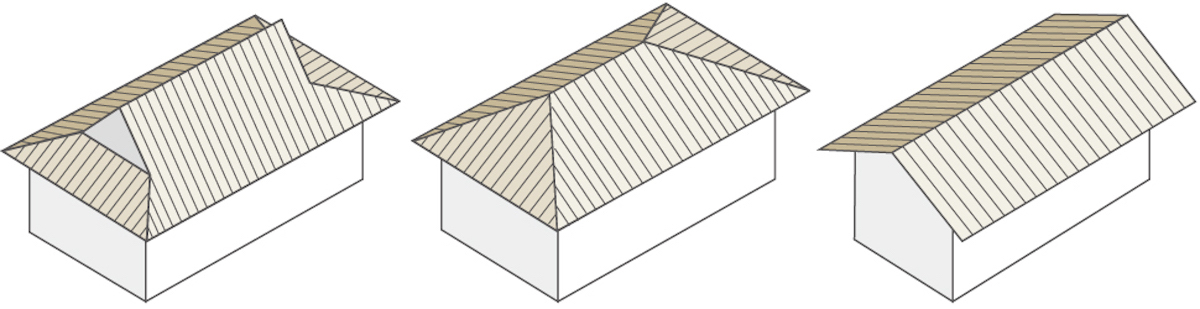

Japanese Roof Shapes

From left: irimoya – hip and gable roof; yosemune – hipped roof; kirutsuma – open gable roof.

The illustration above shows the three typical roof-types of a traditional Japanese house.

The kiritsuma (open gable, right) is the simplest style, with the roof sloping from the ridge down to the eaves on two sides, forming two triangular gables at the narrow ends of the house.

The yosemune (hipped roof, centre) has four sides sloping down from the ridge to the eaves, and has no gables. Two opposing sides of the roof are trapezoid, and the other two triangular.

The irimoya roof (left) combines hips and gables into a single roof. This roof is a two-sided gable roof at the top, but changes into a four-sided hipped roof halfway down.

The exterior walls of the house that align parallel to the ridgeline are known as hira walls, while the shorter end walls under the gables are called tsuma walls. Houses with the main entrance in the tsuma gable end are called tsuma-iri, while those with the main entrance on the side that runs parallel to the ridgeline are called hira-iri.

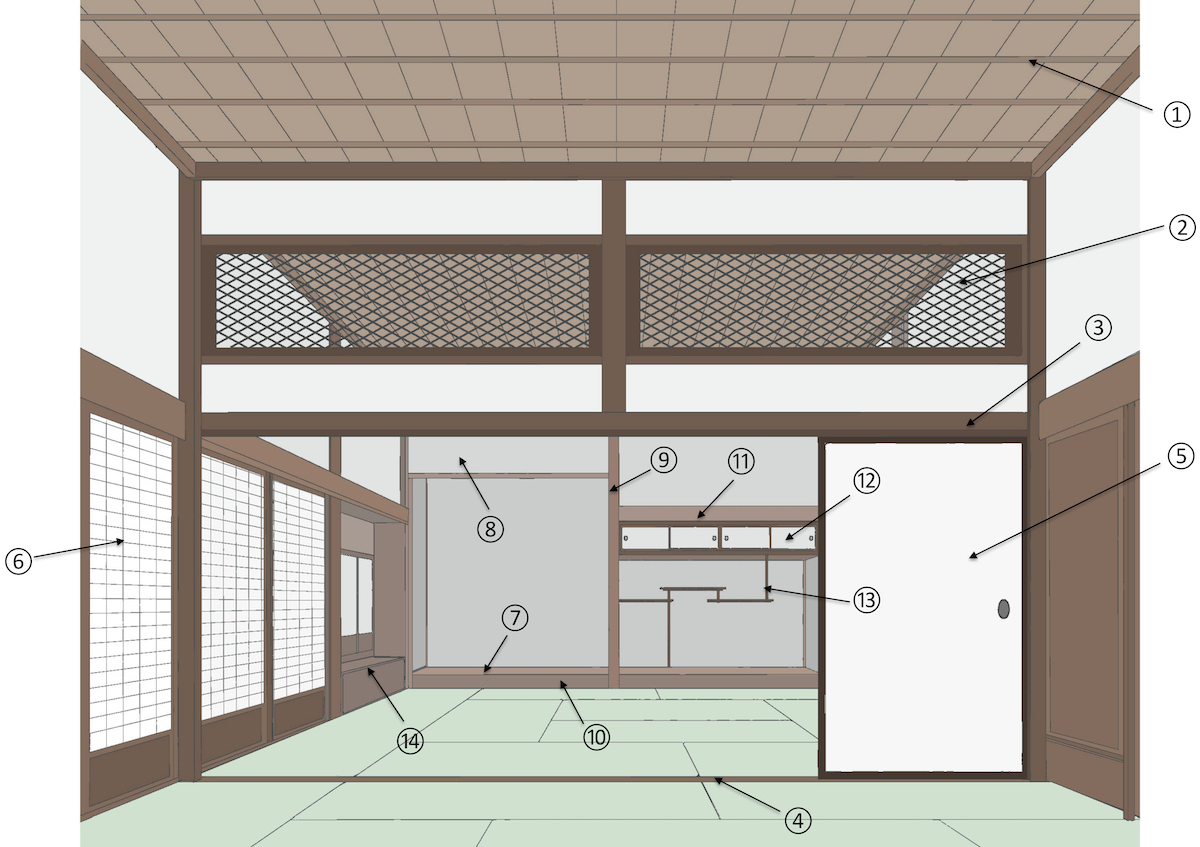

Interior Elements of the Traditional Japanese House

① Saobuchi (竿縁) – Ceiling Battens

Saobuchi are long, narrow battens that support the ceiling boards (tenjō ita). They are both structural and decorative. Saobuchi are usually aligned parallel to the side of the room where the tokonoma (decorative alcove) is, and are spaced at about 30 to 60 centimetre intervals.

② Ranma (欄間) – Transom Panel

A ranma is a decorative open panel in an interior upper wall between the kamoi lintel and the ceiling, that allows light and ventilation. There are many styles of ranma. Kōshi-ranma consist of a simple lattice panel, while shōji-ranma are small sliding panels that can be opened and closed. Sukashibori ranma are carved openwork panels that fit into the ranma frame.

③ Kamoi (鴨居) – Sliding Door Lintel

The kamoi are the lintels above openings for sliding fusuma or shōji door panels. They have recessed tracks for the sliding panels to fit into. Mume-kamoi are lintels that don’t have tracks in them. In sections of wall without any door openings, decorative horizontal timbers called tsuke-kamoi are added to continue the line of the kamoi beams right around the room.

④ Shiki-i (敷居) – Door Sill, Threshold

The shiki-i is the horizontal timber sill at the bottom of a door opening. Shiki-i is also the name given to the timber beam placed over the threshold of a gate or entrance, to separate the interior from the outside. The Japanese expression “shiki-i ga takai” (literally, “the threshold is high”) is a metaphor for a psychological barrier or sense of awkwardness in approaching someone.

⑤ Fusuma (襖) – Sliding Partition Door)

Fusuma are opaque sliding panels used to partition Japanese-style rooms (washitsu). Fusuma consist of a wooden framework covered on both sides with heavy paper or fabric. They are fitted with a frame of lacquered wood around the outer edges of the panel. The term fusuma derives from fusuma shōji, opaque panels used to partition the fusu-ma, or sleeping space. Fusuma may also be known as karakami-shōji, or just karakami.

⑥ Shōji (障子) – Translucent Sliding Screens

Shōji are translucent sliding panels that cover door and window openings, offering privacy while allowing the light to pass through. They consist of a wooden lattice framework covered on one side with stretched shōji paper. Sliding panels with glass on the exterior and shōji panels that can be slid up from the bottom are called yukimi-shōji (snow-viewing shōji).

⑦ Tokonoma (床の間) – Decorative Alcove)

The tokonoma alcove is a decorative element characteristic of the reception room of a Japanese-style home. Recessed into one wall of the room and raised slightly above floor level, it is used to display wall hangings and ikebana flower arrangements. The tokonoma originated in the Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573), when the lord of the house would sit in a separate section of the room with a raised floor when receiving his vassals. This raise floor space was called a toko. Even nowadays, the highest-ranking seating positions in a reception room are those closest to the tokonoma. The kamiza or “seat of honour” is to sit facing the room with one’s back to the tokonoma, just like the lord and master of centuries gone by.

⑧ Kokabe (小壁) – Above-lintel Walls

The kokabe is a narrow horizontal section of wall that extends partway down from the ceiling and stops at about head-height. The section of partial wall that divides the tokonoma alcove from the rest of the room is a kokabe. The timber crosspiece at the base of the kokabe in front of the tokonoma is called an otoshigake. The short sections of wall between the lintels and the ceiling are also called kokabe. Another word for kokabe is sagari-kabe, or “hanging wall”.

⑨ Tokobashira (床柱) – Alcove Pillar

Tokobashira are ornamental posts at either side of the tokonoma alcove. Tokobashira are generally square, but visual interest can be added through the use of round posts, semi-squared posts with bark left on the corners, and posts with chamfered edges.

⑩ Toko-gamachi (床框) – Facing-board

The toko-gamachi is a horizontal decorative board used to cover the front of the raised floor section of the tokonoma alcove. Toko-gamachi are often lacquered, and precious timbers are frequently used as a design feature. Small changes in floor-level are common in traditional Japanese houses, and kamachi is the term for the timber boards used as facings to cover the ends of the floor structure timbers where these levels change. In a Japanese genkan (entrance hall), the piece of timber that covers the step up into the house is called the agari-kamachi (see ⑧ in the irori illustration below).

⑪ Nageshi (長押) – Tie Beams

Nageshi are beams running between the posts of a wall, just above head height. In the past they served as ties to strengthen the building, but nowadays they are mostly ornamental.

⑫ Tenbukuro (天袋) – Overhead Cupboard

The tenbukuro is an overhead cupboard with two or four sliding doors, usually found above the chigaidana or above an oshiire closet. A similar cupboard sometimes located below the chigaidana at floor level is called a jibukuro.

⑬ Chigaidana (違い棚) – Staggered Shelves)

The chigaidana are a set of decorative staggered shelves placed in the recess next to the tokonoma alcove. Chigai-dana consist of two or three shelves placed adjacent to each other at different levels, partially supported by a slim post.

⑭ Tsuke-shōin (付書院) – Writing Bench

The tsuke-shōin is a bench often found under a window near the tokonoma. Also sometimes called an idashifu-tsukue, the tsuke-shōin once served as a study or library space.

The Irori, the Hearth Space

The irori, an open, sunken hearth set within a timber floor, was once a standard fixture in Japanese farm houses. There being no chimney, smoke from the irori drifted up through gaps left for that purpose in the upper storey floorboards, into the roof space and eventually up through the roofing thatch, where the smoke served to preserve the structural timbers of the roof and deter birds and insects from taking up residence in the thatch.

Located adjacent to the doma, the earthen-floored kitchen and utility area, the irori is where the family would gather to eat and relax. Just as with a formal reception room, there is a prescribed seating order around the irori, with the head of the household seated furthest from the kitchen area and the servants seated closest to the kitchen area.

① Daikoku-bashira (大黒柱)

The daikoku-bashira is, symbolically, the main sacred pillar of the house and the embodiment of the family’s health and prosperity. Closely associated with the kitchen and the hearth, it is named for the deity Daikoku, one the Seven Gods of Good Fortune.

② Oza (男座)

The oza is the seating space allocated to a guest, next to the hearth and to the right of the head of the household, who would be seated in the yokoza position (5).

③ Kijiriza (木尻座)

The kijiriza is the seat closest to the earthen-floored kitchen. This is where a servant might sit, or where bundles of firewood might be placed.

④ Jizaikagi (自在鉤)

The jizaikagi is a pot hook that allows a kettle or a cooking pot to be suspended over the hearth. It is adjustable so that the pot or kettle can be raised or lowered, depending on the level of heat required.

⑤ Yokoza (横座)

The yokoza is the seat furthest from the kitchen area, where the head of the household would sit.

⑥ Irori (囲炉裏)

The irori is the sunken hearth once found in all farmhouses, where the family would gather to eat and relax.

⑦ Kakaza (母座)

The kakaza is where the matriarch of the household would sit. Situated to the left of the master of the household and opposite the guest seat, the kakaza was also convenient to the kitchen area.

⑧ Agari-kamachi (上がり框)

The agari-kamachi is the horizontal facing-board that covers the front edge of the step from ground level to the raised floor level of the house.

⑨ Shikidai (式台)

The shikidai is a timber platform or step that extends across the entire width of an entrance.

⑩ Doma (土間)

The doma is a ground-level room, often with a floor of packed earth, but sometimes tile or stone. The doma has direct access to the outside and contrasts with the raised floor of the rest of the house. This is a utilitarian area, a little like a lean-to shed, used for food preparation and activities such as pounding or milling rice.

The Kobayashi Family Residence

Illustrator Yuriko Aso’s drawings for this article were modelled on the Kobayashi Family Residence, an old farmhouse on display in Kawagoe-dō Ryokuchi Kominka-en, a tract of green space in Tokyo’s Tachikawa City. Built in 1852, the farmhouse was lived in until 1988, although some renovations had taken place, including the replacement of the thatched roof with tiles, and the addition of aluminium-framed windows. The home was dismantled and moved to its present site, where it was reassembled and restored to its original state. The Kobayashi Family Residence is open to the public.

Kawagoe-dō Ryokuchi Kominka-en

(Translation: Kawagoe-dō Green Space Folk House Park)

Admission is free of charge.

Open 9:00 – 16:30

Closed Mondays

Address: 4-65 Saiwaicho, Tachikawa, Tokyo.

Phone: 042-525-0860 (Tachikawa City Museum of History and Folklore)