With a population of over one million, the city of Edo (Tokyo) was the world’s largest city by the mid-18th century. In this setting, a unique culture imbued with imagination and creativity was born. The people of Edo continually came up with new design concepts to improve their society and enhance their way of life. Looking at Edo design, we might just pick up a few tips for enriching our own lives. From a design standpoint, we explore the ‘Edo Culture’ that blossomed during the peace of the Edo Period.

Text : 武正秀治 Hideji Takemasa / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Edo / Edo Design Series / Yin and Yang / Edo Period / Samurai / Tokyo / Tokugawa / Feng shui / Tokyo Imperial Palace

Vol.01. Edo Urban Design and the Principles of Yin and Yang: the Magical Lines of Defence that Led to Peace

The project to design the ultimate castle town

The Edo Period (1603-1868), a two hundred and sixty-five year period of peace and prosperity, began with urban design. From the very beginning of the Tokugawa bakufu(military government) in 1603, chief military commander, shōgun Ieyasu Tokugawa, ruler of all Japan, undertook a project to construct a new political and military capital. His plan was to build the ultimate castle town. Once a small fishing village, Edo was transformed into the world’s most populous city. New neighbourhoods for were created for daimyō (feudal lords), samurai and townspeople by moving hills and reclaiming land. Huge amounts of material excavated from the Kanda-Surugadai plateau were used to reclaim the low-lying estuarine area that came up as far as present-day Hibiya Park. In fact, the name, ‘Edo’, is said to derive from the narrow inlet that gave access to the sea through these muddy shallows.

Key design concept: a spiral castle town

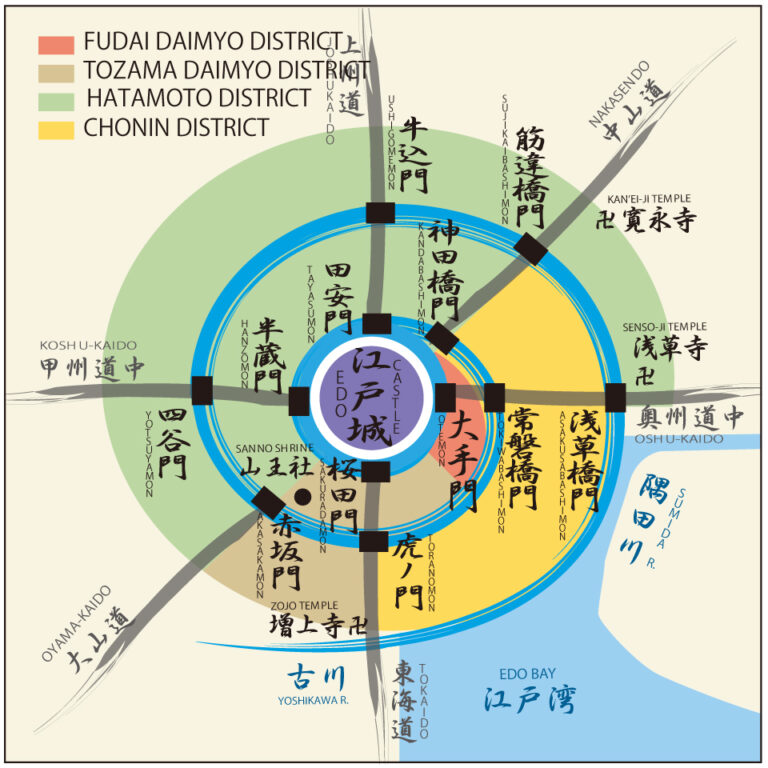

Ieyasu Tokugawa’s aim was to build the ultimate sōkamae that would withstand any adversity, natural or manmade. The term sōkamae denotes a castle town entirely contained within physical defenses such as stone walls and moats. Usually these structures would surround the castle in concentric rings, but at Edo Castle (now the site of Tōkyō Imperial Palace), channels were excavated to form moats in a spiral formation, starting with the castle at the centre, passing through the Kanda River (then called the Hirakawa River) and spilling into the Sumida River (formerly the Ōkawa River). Defence was not the only role the spiral moat played. Being a continuous channel, it also functioned as an aqueduct for the transportation of construction materials and other goods.

During the feudal era, areas where people could live were strictly circumscribed according to social class. Due to the unique spiral layout, the various sections of the city that were designated for temples and shrines, samurai families, and townspeople were adjacent to each other rather than separated by moats or walls as would be the case with a conventional sōkamae layout. The image below shows how land use was divided. The fudai daimyō were loyal retainers, part of the government, with access to the shogun, and were located close to the castle. The tozama daimyō were potentially hostile lords, excluded from Edo politics and carefully controlled. They were required to maintain a household in Edo in addition to their own domains, and to reside in Edo every second year. The hatamoto and gokenin were loyal samurai who served the Tokugawa bakufu and maintained peace in the city. The chōnin or ‘townspeople’ were merchants and artisans who supplied the needs of the military classes and whose creativity gave birth to Edo’s unique sense of style.

Vestiges of the old Edo layout remain in the iconic Ginza district, where several of the tall buildings that front onto Ginza Chuō-dōri Street seem improbably narrow for their height. This odd narrowness could be ascribed to the high cost of land in this upscale district, but actually, these buildings sit on plots of land whose boundaries remain unchanged since the days of Edo, when Ginza was inhabited by artisans, merchants and performing artists.

A mystical design to safeguard the city

The planning of Edo was a pragmatic undertaking, and the urban designers used all resources available to them, including the mystical powers of divination – the philosophies of yin and yang and feng shui that had been a natural part of urban design since ancient times. Edo’s designers used these principles to draft a defensive design to safeguard the Tokugawa bakufu from disruptive events such as natural disaster or political unrest.

Particular attention was paid to the geomancy of Kyōto, the imperial capital that had stood for hundreds of years. Magical defensive lines were constructed in a bid to recreate Kyōto’s auspicious features. In the northeast of Kyōto, an inauspicious direction, Enryaku-ji Temple watches over the city from atop Mount Hiei. In Ueno, to the northeast of Edo castle, Tōeizan Kan’ei-ji Temple was constructed (Tōeizan means Hiei of the East) to improve the energy from this inauspicious direction. Shinobazu Pond in Ueno represented Lake Biwa near Kyōto, and here Benten-dō Temple, dedicated to the watery goddess of prosperity, was built on an island to emulate Hōgon-ji Temple on Lake Biwa’s Chikubu Island. As an added measure, the Ueno hillsides were planted with flowering cherry trees especially brought in from Mount Yoshino in Nara.

Redesigning the capital for times of peace

The population of Edo grew rapidly and by 1657 the city was bursting at the seams. This is when the Great Meireki Fire broke out. The fire raged all across the city for three days, driven by changes in the wind. Most of the buildings within the Edo Castle complex were consumed and almost two thirds of the city burned to the ground. An estimated 100,000 lives were lost.

More than fifty years after Edo had been established as a military stronghold, the tragedy of the Great Meireki Fire prompted the government to rethink the city design. Rather than prioritizing military defences, the new overarching design concept was ‘a capital for times of peace’. Key to this concept were the expansion of city facilities and the provision of urban infrastructure. This was the grand design of a government that intended to be in power for a long time to come.

The implementation of the planning concept required large-scale reconfiguration of land use. To begin with, the temples and shrines, which took up so much space, were relocated to the outskirts of the city. Even the Yoshiwara pleasure district, which had been in Ashiya-cho (present-day Ningyōchō) in Nihonbashi, was rebuilt in the rice-growing area of Asakusa-tambo (present-day Nihonzutsumi). The land that was opened up could then be used for new districts for samurai and townspeople.

The bakufu could not risk another disaster like the great fire, and they also needed more space for the city to expand. Wide avenues were established throughout the city to serve both as firebreaks and as major thoroughfares to provide better and safer access. Two bridges, Ryōgoku-bashi and Eitai-bashi were built across the Ōkawa (Sumida) River, which had claimed the lives of so many victims fleeing from the fires. A major route constructed out to the Honjo and Fukagawa areas to the east of the city allowed for urban expansion, while also serving as a firebreak. This city layout persisted until the Meiji Restoration of 1868, which saw the demise of the Tokugawa bakufu, the forfeiture of all Tokugawa lands and the abolition of the strict class system.