Everyday objects meticulously fashioned by skilled craftspeople – in Japan we’ve grown used to having hand-crafted tools and objects around us. Yet, the very existence of the knowledge and skills that bring us these valued objects is under threat. Now is the time to consider the importance of our traditional arts and crafts.

Text : 中澤浩明 Hiroaki Nakazawa / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Akita Prefecture / Artisans / Aomori Prefecture / Nibutani Ita / Cast Iron / Fukushima Prefecture / Ainu / traditional crafts / Lacquerware / Hokkaido / Traditional Crafts Series / Nambu Tekki / Miyagi Prefecture / Yamagata Prefecture

A legacy of objects handcrafted for everyday life, each with its own unique grace

In Japan we have a long history of using the natural materials around us to craft objects for everyday use. These have always been essential items, in keeping with our lifestyles and the climate and natural features of our surroundings, and crafted using the skill and ingenuity handed down by our predecessors. Yet nowadays, modern living, coupled with the ready availability of low cost synthetic materials, mean that the use of handcrafted household items has declined sharply. To address this problem, the government passed the Densan (Traditional Industries) Act in 1974, which aims to support industries producing traditional crafts by offering financial assistance to those that meet the criteria. To meet the Densan criteria and be designated as ‘Traditional Crafts’, products should be used mainly in everyday life, largely handmade, crafted using traditional techniques and from traditionally used raw materials, and the industry should be traditional to its region. As of writing, 230 items Japan-wide have met these criteria and are officially recognised as Traditional Crafts.

Let’s take a region-by-region look at the charm of these traditional crafts so that we can learn more about the regional cultures, lifestyles and environments from which they were born, and the legacy of the skilled craftspeople that create them.

In this article, we explore the traditional crafts of Japan’s northernmost regions, Hokkaidō and Tōhoku.

Characteristics Unique to Hokkaidō and Tōhoku

The delicate handicrafts of the indigenous Ainu people in Hokkaidō, and the regionally distinctive charm and simplicity of Northern Honshū

In Hokkaidō, despite the Ainu people’s long craft heritage, a lack of written records had made it difficult meet the Traditional Craft criteria. No traditional industries had received official designation until 2013, when two workshops in the Nibutani District of Biratori were approved.

In northern Japan, products such as Naruko lacquerware, Aizu-nuri lacquerware and Nanbu-tekki ironware were developed by adding unique innovations to technology brought to the region hundreds of years ago from central Japan. These items have become highly valued and are now considered to be specialty products of the region. Products native to the Tōhoku area include Oitama tsumugi silk, traditional Miyagi kokeshi dolls, and woodcrafts from Akita, which is rich in forestry resources. Additionally, shōgi (a board game similar to chess) pieces from Tendō City have provided great publicity for the region as a unique and traditional craft, as a result of recent shōgi craze.

Hokkaidō

Nibutani Ita Wooden Trays / Nibutani Attoushi Bark Fibre Cloth

Nibutani ita is a type of wooden tray from the Sarugawa River area of Nibutani, which features carved spirals and fish scale patterns unique to the Ainu people. Nibutani Attoushi is a fabric woven from fibres taken from the bark of several species of elm and zelkova trees. Water-resistant and with excellent ‘breathability’, it is a durable fabric with a distinctive texture, used mainly for clothing. Both products were designated as Traditional Crafts in 2013.

Aomori Prefecture

Tsugaru-Nuri Lacquerware

The production of Tsugaru-Nuri lacquerware began towards the end of the 17th Century as part of a drive by the feudal lord of Tsugaru, now Aomori Prefecture, to develop local industries. There are four distinctive lacquer techniques: Kara-nuri, which results in multi-colored speckling; Nanako-nuri, a circular pattern; Monsha-nuri, with small dots and swirling patterns, and Nishiki-nuri, which combines circles, swirls, and lines. The word, nuri, by the way, means painted or lacquered. Each of these techniques involves the application of dozens of layers of lacquer, each of which is allowed to dry and is polished before applying the next layer. The stunningly elegant and refined finished products are therefore also extremely durable and practical. The technique is used to produce not only dishes, but also trays and low tables.

Iwate Prefecture

Nanbu-Tekki Ironware / Iwayadō Tansu Chests / Hidehira-Nuri Lacquerware / Jōbōji-Nuri Lacquerware

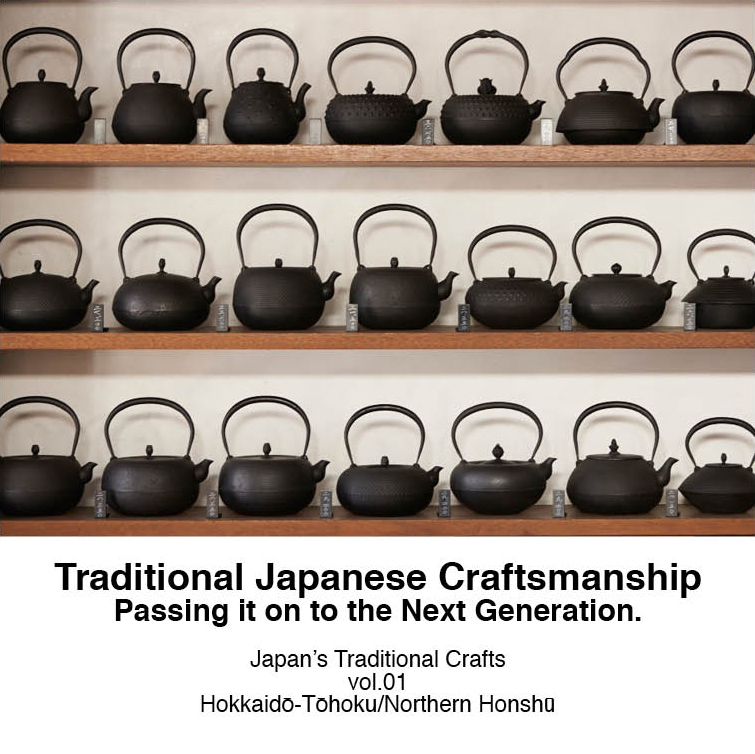

From the Nanbu region in the far north of Aomori, Nanbu-tekki ironware, with its delightful dotted pattern and long-lasting durability, is one of the best known of all the traditional crafts. Production began in the mid-17th Century, when ironworkers were invited to the region by the feudal lord of Nanbu.

Iwayadō Tansu are lacquered chests made from zelkova or paulownia timber, and furnished with elegant metal fittings.

Production of Hidehira-Nuri lacquerware began at the behest of military commander, Fujiwara-no-Hidehira in the late Heian Period (794 – 1185). These gorgeously embellished pieces of lacquerware combine the radiance of gold leaf with the rich gloss of lacquer.

In contrast, Jōbōji-Nuri lacquerware is made in a single, unadorned colour, usually black, vermilion or natural wood, and features a restrained matte sheen. Jōbōji-Nuri items are used in daily life.

Miyagi Prefecture

Naruko-Shikki Lacquerware / Ogatsu-Suzuri Ink Stones / Miyagi Traditional Kokeshi Dolls / Sendai Tansu Chests

The production of Naruko-Shikki lacquerware in the Naruko region of Miyagi Prefecture was developed and extended in the early Edo Period (1603 – 1868), when craftsmen were dispatched to Kyōto in order to refine their skills.

Ogatsu-Suzuri ink stones have been valued for their excellent qualities since the Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573) and are still made by hand using traditional methods. There are five different types of traditional Miyagi Kokeshi dolls, each with its own distinctive shape and style of painting. They are: Naruko kokeshi; Sakunami Kokeshi; Tōgatta Kokeshi; Yajirō Kokeshi, and Hijiori Kokeshi.

Sendai Tansu chests were developed in Sendai as a local industry during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868). The chests are finished with finely rendered iron fittings and kijiro lacquer that highlights the natural wood grain.

Akita Prefecture

Kawatsura-Shikki Lacquerware / Kabazaiku Cherry Bark Woodcraft / Ōdate Mage-Wappa Bentwood / Akita Sugi Oke Taru (Cedar Pails and Barrels)

The production of Kawatsura-Shikki lacquerware is said to have started during the Kamakura Period (1185 – 1333), but it was during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) that the production of lacquered bowls took off in earnest. Great emphasis is placed on hardening the wood and on the undercoating process, even before the lacquer is applied, resulting in extremely durable and practical pieces.

Unique to this region, treasured Kabazaiku cherry bark woodcraft is made by applying a thin veneer of wild cherry bark to wooden items.

Both Ōdate Mage-Wappa bentwood containers and Akita Sugi Oke Taru pails and barrels are crafted from local Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica), a stable timber with low tendency to shrink or expand. With their beautiful wood grain and fresh wood scent, these items add a familiar warmth to everyday life.

Yamagata Prefecture

Oitama Tsumugi Silk / Yamagata Imono Cast Iron / Yamagata Butsudan Buddhist Altars / Tendō Shōgi Pieces / Uetsu Shinafu Tilia Bark Cloth

The term Oitama Tsumugi refers to six types of silk cloth which are yarn-dyed using locally produced plant dyes. It became popular in the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) due to promotion by local feudal lord, Uesugi Kagekatsu.

Yamagata Imono cast iron kettles and vases have been indispensable to the Japanese tea ceremony since the middle of the Heian Period (794 – 1185).

During the Edo Period, carvers who produced carved lintels and Buddhist altar fittings were joined by lacquer craftsmen, gold lacquer craftsmen, and decorative metalwork craftsmen to create Yamagata Butsudan household Buddhist altars.

Local production of Tendō Shōgi pieces began the late Edo Period when cash-strapped samurai families were directed to make them in order to supplement their incomes. Uetsu Shinafu cloth is an ancient textile woven from fibres produced from the bark of wild Tilia tree species.

Fukushima Prefecture

Ōbori-Soma Yaki Ceramics / Aizu-Hongō Yaki Ceramics / Aizu-Nuri Lacquerware / Oku-Aizu Amikumi Zaiku Basketwork / Oku-Aizu Shōwa Karamushi-Ori Weaving

Ōbori-Soma Yaki ceramic ware has a blue-hued enamel, or celadon, glaze with distinctive ‘blue cracks’ as a characteristic feature. Aizu-Hongō Yaki ceramics flourished during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) under the patronage of the local feudal lords.

Thought to date back to the Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573), Aizu-Nuri lacquerware bowls, layered boxes and trays are crafted using a wide range of lacquer techniques.

Oku-Aizu Amikumi Zaiku basketwork pieces include hand and shoulder baskets, as well as sweet dishes, woven from wild grapevine or silver vine (Actinidia polygama) gathered from the local forests. Each item has a lovely simplicity.

Oku-Aizu Shōwa Karamushi-Ori weaving utilizes nettle fibres (ramie) to produce a cloth with excellent moisture-wicking and fast-drying properties. Among the most ancient of textiles, karamushi-ori cloth is used to make clothing and accessories.