We have a long history in Japan of using the natural materials around us to craft objects for everyday use. These have always been essential items, in keeping with our lifestyles and the climate and natural features of our surroundings. Such items are still crafted using the skill and ingenuity handed down by our predecessors. Yet nowadays, modern living, coupled with the ready availability of low cost synthetic materials, mean that the use of handcrafted household items has declined sharply.

To address this problem, the government passed the Densan (Traditional Industries) Act in 1974, which aims to support industries producing traditional crafts by offering financial assistance to those that meet the criteria. To meet the Densan criteria and be designated as ‘Traditional Crafts’, products should be used mainly in everyday life, largely handmade, crafted using traditional techniques and from traditionally used raw materials. Additionally, the industry should be traditional to its region. As of writing, 230 items Japan-wide have met these criteria and are officially recognised as Traditional Crafts.

In this series we take a region-by-region look at the unique features of these traditional crafts and the legacy of the skilled craftspeople who keep these precious skills alive.

Text : 中澤浩明 Hiroaki Nakazawa / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Chiba Prefecture / Traditional Crafts Series / Edo Style / Saitama Prefecture / Tokyo / Gunma Prefecture / Ibaraki Prefecture / Kanagawa Prefecture / Tochigi Prefecture / Traditional Skills

Features of the Kantō Region. The Style and Sophistication of Edo Design

Tōkyō, formerly known as Edo, was the headquarters during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) of the bakufū military government, headed by the shōgun. As the culture of the ‘townspeople’ of old Edo matured, a wide variety of luxury objects and amusement items were developed to suit the tastes of the up-and-coming civilian classes. This period gave rise to numerous traditional handcrafts imbued with the essence of Edo design, meticulously finished and stylishly chic.

Ibaraki Prefecture

Yūki-tsumugi Silk (listed also under Tochigi Prefecture)/Kasama-yaki Pottery/Makabe Ishidōrō Stone Lanterns

Yūki-tsumugi silk weaving began during the Nara Period (710 – 794). During the Kamakura Period (1185 – 1333) it became known as Yūki-tsumugi. It was named after the feudal lord who worked to protect and develop the craft. This high quality silk cloth is crafted entirely by hand, from the spinning of the thread to the weaving of the cloth.

Kasama-yaki pottery (Kasama ware) was first produced during the middle of the Edo Period (1603 – 1868) when a potter from the Shigaraki area was asked to construct a kiln in the Kasama area. Today Kasama-yaki potters produce a everyday items such as crockery as well as ornamental pieces. Stone has been used in the Makabe area to craft everyday implements since ancient times.

The production of Makabe Ishidōrō stone lanterns is said to have started

during the late Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573) with the production of Buddhist statuary, using local granite.

Tochigi Prefecture

Yūki-tsumugi Silk (listed also under Ibaraki Prefecture)/Mashiko-yaki Pottery (Mashiko Ware)

Silk cloth production has flourished in the Oyama City area of Tochigi Prefecture for hundreds of years. Yūki-tsumugi silk cloth was woven as a way of providing an income during the agricultural off-season. It was already being supplied to the imperial court by the Nara Period (710 – 794).

Production of Mashiko-yaki pottery started in the mid-19th century, having come under the influence of Kasama-yaki. Large quantities of the distinctive Mashiko-yaki pottery featuring traditional techniques such as ‘white cosmetic’ glaze and brush mark slip decorations are produced from the good quality local Mashiko clay.

Gunma Prefecture

Isesaki-kasuri Cloth/Kiyrū-ori Weaving

Although the production of Isesaki-kasuri cloth dates back to ancient times, a production centre for this resist-dyed cloth was not established until the latter half of the 17th century. The cloth was known in Japan as “Isesaki-meisen” from the time of the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912). Patterns range from simple criss-cross kasuri patterns to intricate and precise designs. Entirely handcrafted, the kasuri technique highlights the best qualities of the silk.

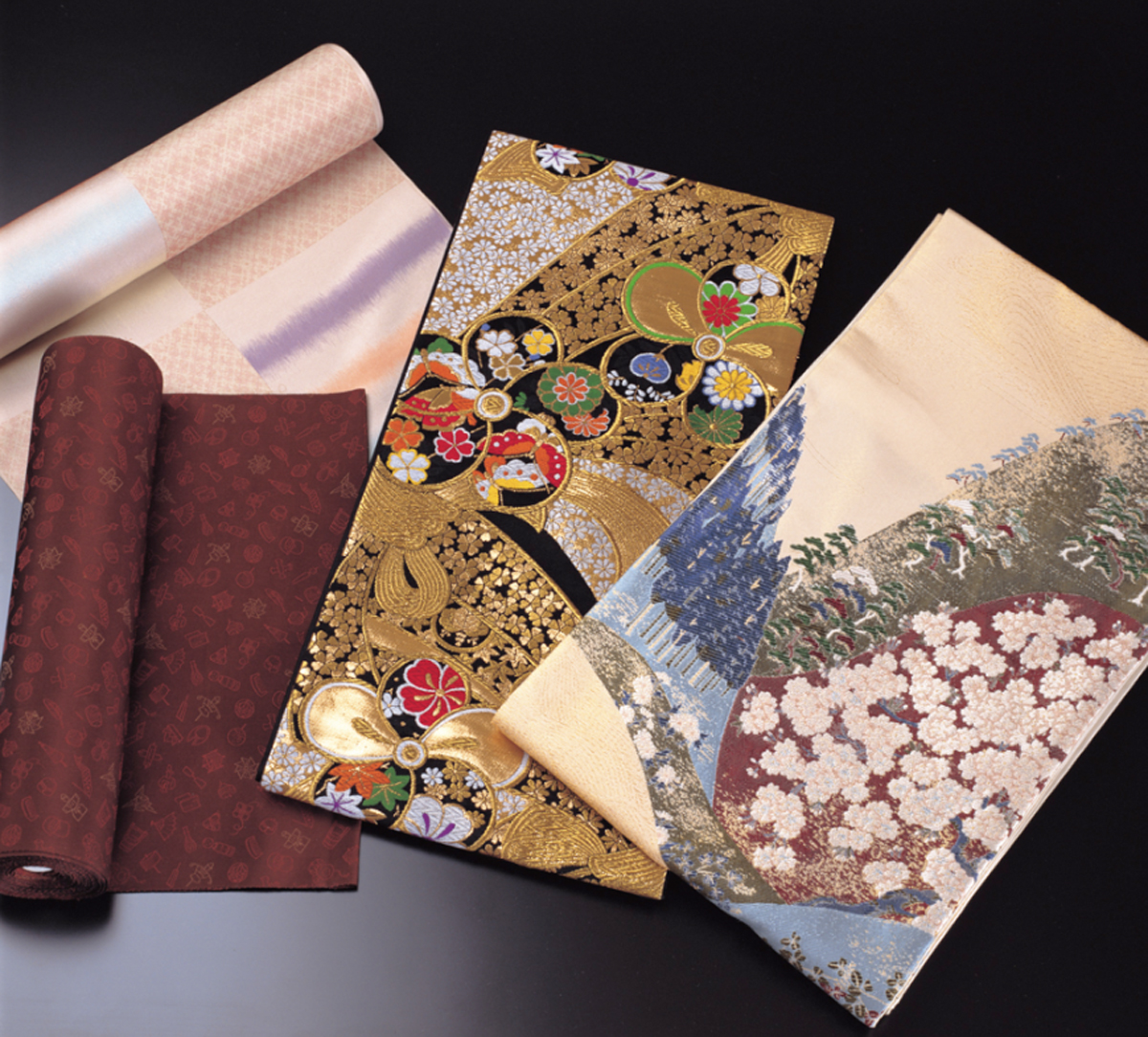

Kiryū-ori is a brocade fabric said to have originated during the 8th century. Mention of the fabric appears in records from the Heian (794 – 1185) and Muromachi (1336 – 1573) Periods. Together with Nishiki-ori brocade from Kyōto, the production of Kiryū-ori later came under the protection of the Tokugawa shogunate. Kiryū-ori was even known as the “Nishiki of the east”.

Saitama Prefecture

Chichibu-meisen Silk/Kasukabe Paulownia Chests/Edo Kimekomi Ningyō Dolls (listed also under Tokyo)/Iwatsuki Ningyō Dolls

Chichibu-meisen silk textiles appeared during the Edo Period (1603 – 1868). During the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912) a patent was granted for the unique hogushi nassen dye technique and the industry prospered. The cloth is characterised by decorative patterns featuring plants and flowers, and by its iridescent lustre, obtained by using complementary colours in the weft threads.

Kasukabe paulownia chests were first made during the early Edo Period when artisans who had come from Kyōto to work on Nikkō Tōshōgū Shrine settled in the area and began making chests from the local paulownia wood. Iwatsuki dolls also appeared in the early Edo Period.

Edo kimekomi dolls were first made in Kyōto and were known as Kamo ningyō dolls. The industry later took root in the Tōkyō area.

Chiba Prefecture

Bōshū Uchiwa Fans/Chiba Kōshōgu Artisan Tools

Bōshū uchiwa fans started to be made by local fishermen’s wives and the elderly as ‘piece work’ during the 1920s. They are now among Japan’s three most famous uchiwa fans, along with Marugame uchiwa (Kagawa Prefecture) and Kyō uchiwa (Kyōto). Locally-grown bamboo is painstakingly split to form the skeleton framework of the fan, over which patterned fabric is glued.

Chiba Artisan Tools have been made in several locations in Chiba Prefecture for centuries. Towards the end of Japan’s feudal period and the early years of the Meiji Restoration, as the nation modernised and adopted aspects of Western culture, Chiba Artisan Tools extended its range in an effort to supply domestically produced Western implements such as scissors and meat cleavers. The tradition continues today with made-to-order production that aligns with customers’ preferences and needs.

Tokyo

Murayama Ōshima Tsumugi Silk/Honba Kihachijō Silk/Tama-ori Weaving/Tōkyō Some Komon Dyeing/Tōkyō Tegaki Yūzen Hand-painted Kimono/Edo Sashimono Cabinetmaking/Edo Wasao Fishing Rods/Tōkyō Ginki Silverware/Edo Kimekomi Ningyō Dolls (also listed under Saitama Prefecture)/Edo Karakami Paper/Edo Kiriko Glassware/Edo Sekku Ningyō Dolls/Edo Mokuhanga Prints/Tōkyō Muji-zome Dyeing/Edo Garasu Glassware/Edo Bekkō Tortoiseshell/Tōkyō Antimony Silver Craft

Most of Tokyo’s designated traditional crafts were perfected during the Edo Period. Murayama Ōshima Tsumugi silk fabric is produced on Amami-Ōshima Island. It is characterised by precise and intricate kasuri patterns in subtle, muted colours.

Tōkyō Some Komon fine pattern dyeing uses Ise-katagami stencils for its minute patterns.

The patterns on each Tōkyō Tegaki Yūzen hand-painted kimono are created entirely by an individual artisan and are generally characterised by a restricted colour palette.

Honba Kihachijō is a silk fabric from Hachijō Island woven from threads coloured with natural plant dyes produced on the island. The fabric is characterised by striped, checked and plaid patterns in yellows, blacks and reds.

Tama Ori are woven silk fabrics produced in the Hachiōji City area of Tōkyō. Tama Ori has been produced since at least the “Warring States Period” c. 1467-1600.

Edo Sashimono cabinetmaking is fine joinery crafted without the need for nails or other metal fastenings.

Edo Wasao bamboo fishing rods are jointed fishing rods assembled from several different types of bamboo and coated with lacquer.

Tōkyō Ginki antimony craft is forged and engraved silverware such as tea ceremony items and vases.

Edo Kiriko cut glass is said to have begun when artisans started using emery powder to create designs on glassware.

Tōkyō Muji-zome dyeing is a process whereby woven textiles and yarns are dyed in single colours from a colour palette of 170 shades.

Kanagawa Prefecture

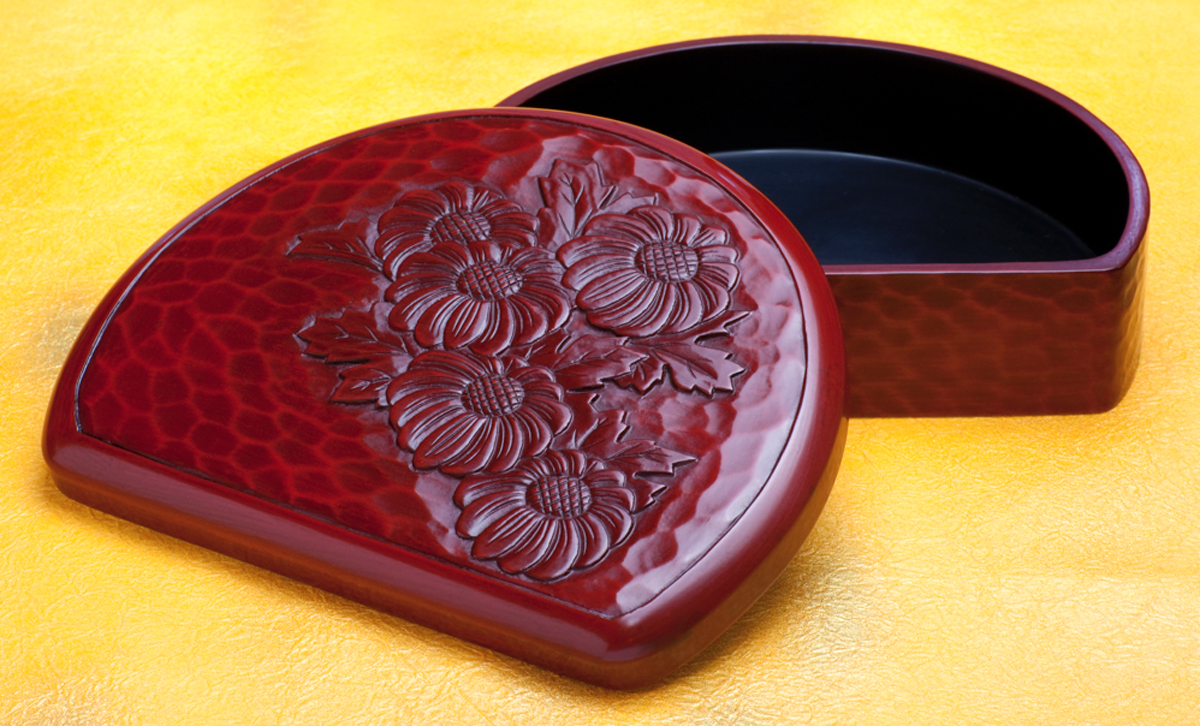

Kamakura-bori Carved Lacquerware/Odawara Shikki Lacquerware/Hakone Yosegi-zaiku Marquetry

Kamakura-bori wooden trays, bowls and boxes feature three dimensional relief carved designs and are finished with layers of lacquer. Production is said to have started during the Kamakura Period (1185-1333).

Odawara Shikki lacquerware has been produced since the middle of the Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573). It is said to have begun by applying lacquer to the turned wooden bowls made using the wide variety of timber growing in the Hakone mountains.

Hakone Yoseki-zaikumarquetry originated in the late Edo Period (1603-1868) when pieces of different types of wood were assembled to create geometric patterns. This developed into the intricate repeated geometric patterns of today’s koyosegi puzzle boxes.