Since ancient times, powerful deities have been said to dwell in the mountains of Kumano. Pilgrims visiting this isolated place faced many hardships along their journey, but still they came, placing their trust in a tolerant, all-embracing faith which held that the gods ‘do not discriminate between the faithful and faithless, the pure and impure’.

Text : Yūji Fujinuma / Photos : 菅原孝司 Koji Sugawara / English Version : Judy Evans

Keyword : Shintō / Kumano / Shrines / Kii Peninsula / Temples / Kumano Kodō / Hiking / Faith / History / Pilgrimage / Buddhism / Landforms

Shinto and Buddhism mingle in the ‘Pure Land’ of Kumano’s mountains

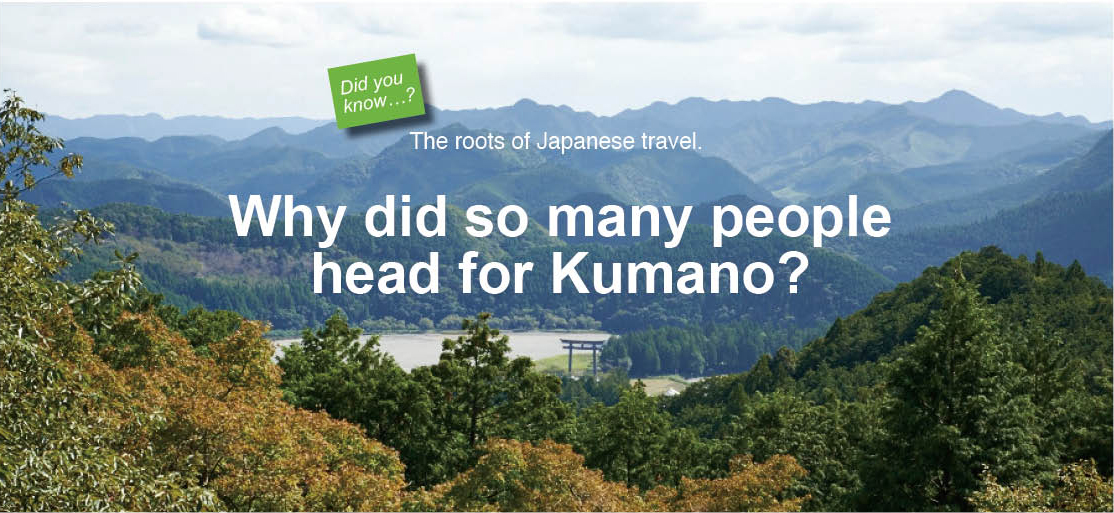

Kumano has been a place of deep spiritual significance since prehistoric times and is considered to be one of the spiritual heartlands of Japan. Situated in the southern part of the Kii Peninsula, south of the ancient capital of Nara, the Kumano region appears as an endlessly unfolding landscape of mountains and hills, extending almost to the coastline. This mountainous landscape is referred to in Japanese as Kumano Sanzen Roppyaku Ho, or the ‘3,600 Peaks of Kumano’. Rich forests abound, supported by a mild climate and plentiful rainfall. Secluded places hidden within the steeply carved valleys seem to belong to a mystical realm. It was in Kumano, at Gotobiki Rock, that three powerful kami (deities or ‘spirits of nature’ in the Shintō faith) are said to have descended from heaven to dwell on Earth. Over time, shrines were built to honour the kami, and pilgrims travelled from far and near to offer their prayers.

The three Grand Shrines built to honour the Kumano kami, Hongu-Taisha, Hayatama-Taisha and Nachi-Taisha, came to be known as Kumano Sanzan (the three mountains of Kumano). Originally, each of the kami was worshipped separately at different shrines, but from the middle of the Heian Period (794 – 1185), people began to worship the kami together at the same place, and a new type of faith evolved.

In the mountains of Kumano, Shintō’s ancient beliefs and reverence for nature fused with new ideologies from the Buddhist teachings that were popular at the time. Grounded in a belief that the Shintō kami were alternate manifestations of Buddhist deities, the three great kami of Kumano, Kumano-Nimasu-no-Ōkami (literally, the great deity who resides in Kumano), Kumano-Hayatama-no-Ōkami, and Kumano-Musubi-no-Ōkami were adopted into Buddhist practice. Kumano-Nimasu-no-Ōkami assumed the form of the Bodhisattva Amitābha, saviour of souls; Kumano-Hayatama-no-Ōkami, the Bodhisattva of Healing, and Kumano-Musubi-no-Ōkami, the thousand-armed Bodhisattva Kannon, Goddess of Mercy. In this way, ancient beliefs blended with new ideas and the unique Kumano Faith emerged. Buddhist temples were integrated with Shintō shrines, and Kumano came to be seen as the earthly manifestation of the Buddhist Pure Land from Mahayana Buddhism.

After the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate and the 1868 Meiji Restoration, new laws mandated that the Shintō kami be disentangled from the Buddhist deities, and the Buddhist temples separated from the Shintō shrines. Two Buddhist temples in Kumano, Seiganto-ji and Fudarakusan-ji that were integrated into the Grand Shrine sites, had to be separated. However, old beliefs linger and at Kumano, traces of the old relationship between the two faiths remain.

Did the Kumano pilgrimages of the imperial household and the aristocracy lead to the nation’s decline?

The first record we have of an imperial pilgrimage to Kumano is that of Emperor Uda (who later abdicated to devote his life to Buddhism) in the early 10th Century. Subsequently, throughout the 11th and 12th Centuries, there was a continual succession of imperial pilgrimages, involving both current and retired emperors. Gradually, these pilgrimages assumed the trappings of a national event, with Emperor Go-Shirakawa and his retinue making thirty-four annual pilgrimages, and Emperor Go-Toba visiting every ten months for a total of twenty-eight pilgrimages.

The fashion spread among the imperial women’s households and other nobles, who, despite being derided as ‘copy-cat pilgrims’, made repeated pilgrimages as if in competition with each other. One of the reasons for their enthusiasm is that they had been told by Buddhist ascetics that the more pilgrimages they made, the better their chances of salvation. Led by Yamabushi, ascetic monks, pilgrims undertook several days of religious purification, including abstaining from eating meat, in preparation for their journey. Purification rituals along the way included cold water and salt water purification, offerings to the divinities at important points along the way, the reading of sutras, and the performance of sacred music and dance.

These imperial pilgrimages necessitated huge retinues of guards and servants, which in turn became an enormous burden for the local people who lived along the route and were ordered to cater to their needs. For instance, Emperor Go-Shirakawa’s pilgrimage of 1118 involved an entourage of 814 people. 185 pack horses, as well as food provisions and other supplies were requisitioned from the populace. Emperor Go-Toba’s pilgrimage of 1212 required the provision of twenty koku of rice per day. With one koku the equivalent of around 150 kilograms, this amounts to about three tons per day!

The emperor’s chief advisor, Fujiwara no Tadazane and poet, Fujiwara no Teika, cautioned against these repeated pilgrimages, saying that they would lead to the downfall of the nation. At one time, when the entire household had gone off on yet another pilgrimage, Fujiwara no Teika lamented in his journal that the popularity of the Kumano pilgrimage had become excessively overheated.

The Samurai spread the Kumano faith across Japan

After Japan had come under military rule in the Kamakura Period (1185 – 1333), the Shōgun and his commanders did not make the pilgrimage to Kumano themselves, but the politically powerful Masako Hōjō is recorded as having made the pilgrimage twice. Although from a samurai household, it seems that Masako Hōjō followed the same purification and devotional rituals that the imperial entourages before her had followed.

After the Jōkyū Rebellion of 1221, pilgrimages became popular among the provincial samurai. Not content with making just one pilgrimage, it was common practice to make at least two or three, and some samurai went every year. Samurai pilgrims even travelled from as far away as northern Honshū, a round trip of some seventy days, to fulfil their dream of making the pilgrimage. In the hope of securing peace and prosperity for their regions, these provincial samurai took the Kumano kami back with them to the provinces through a process called kanjō, whereby the kami is divided and propagated (without weakening the properties of the original kami). The kami were enshrined in the provinces, leading to a proliferation of Kumano shrines all over Japan. Today there are about three thousand Kumano Shrines in Japan.

During the Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573) the popularity of the Kumano pilgrimage spread to the general populace. At this time, lines of pilgrims were so numerous on the route that their visits came to be referred to as ‘ant processions’. As well as women, all manner of people were accepted on the Kumano trail. Many devotees made the pilgrimage in the belief that it had the power to heal illnesses and confer good health.

Physical disabilities did not prevent people from making the pilgrimage. For the people who lived along the route, helping those in need was a form of piety. Those who could not walk could be pulled along in small carts or barrows. This practice is thought to have been the basis of the Legend of Hangan Oguri, where the hero, nobleman Oguri, at death’s door and unable to walk, was borne in a hand cart to the healing waters of Yunomine, where he was restored to health.

A timeless journey to the Pure Land

Factors that enabled commoners to take part in the Kumano pilgrimage include the development and spread of a monetary economy, and the establishment of roadways and lodging houses. Whereas previously, everything from food supplies to expedition equipment had to be trekked into the mountains, the move to a cash system meant that these necessities could be acquired as and when required, allowing pilgrims to travel lightly.

Although the popularity of the Kumano pilgrimage declined in the modern era, with the pilgrimage route itself becoming neglected as the Kumano Faith declined, there was a time when maintenance of the Grand Shrines was financed with support from the shogunate. In recent years, support from the Government has once again been forthcoming. First, Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs identified the pilgrimage route as a significant part of their ‘Roads of History’ project, which directed attention to the area. Then, more recently, the sacred sites of Yoshino and Omine, Koyasan, and the Grand Shrines of Kumano, as well as the pilgrimage routes linking them, were designated as UNESCO World Heritage sites, under the name, Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range. The Kumano pilgrimage routes and its temples and shrines are once again being cared for and maintained.

What compelled so many people to make the pilgrimage to Kumano? Perhaps they sought the Pure Land of the Buddhist celestial realm, and perhaps, also, they made the journey in the faith that Kumano itself was a Pure Land here on Earth, one that could confer spiritual benefits in this world. Whatever the reasons, the ancient paths that lead through Kumano’s deep and mysterious forests, redolent with a sense of the supernatural, continue to evoke the atmosphere of those old days, even now.